Glenda Jackson is holding court at a noisy New York City diner on a Sunday afternoon. "I'm done with this," she barks, handing an unfinished fruit salad to the waiter. "And take their orders." The waiter, more bemused than affronted, looks at the two women seated in the booth across from Jackson. They dutifully order.

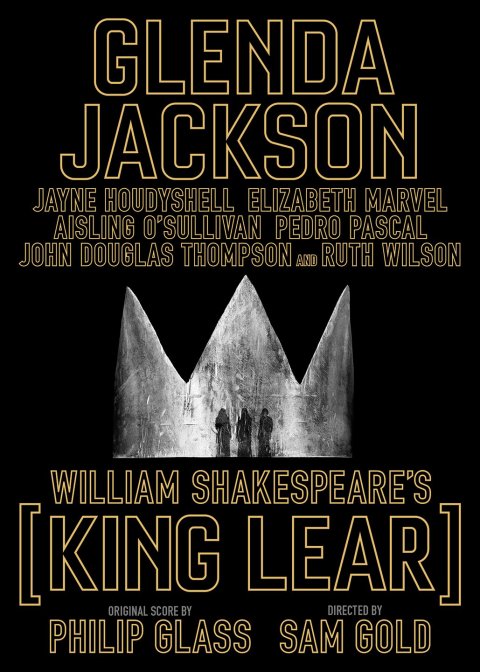

Jayne Houdyshell and Elizabeth Marvel are Jackson's co-stars in a gender-bending production of William Shakespeare's King Lear, currently occupying the Cort Theatre on Broadway. Despite their own busy, esteemed careers (among other honors, Houdyshell won a Tony for 2016's The Humans), they are clearly awed by their entertainingly spiky star. Well, who wouldn't be?

In late 2016, Jackson returned to the London stage after over 20 years as a member of Parliament. The role was Shakespeare's mad king, her performance a critically acclaimed barn burner. Jackson, who was 81, then hightailed it to Broadway, picking up a Tony in 2018 for Edward Albee's Three Tall Women. After a short breather—"mostly on grandma patrol," she says—she's reprising her Lear in New York. The production, directed by Sam Gold (Tony Award winner for 2015's Fun Home), is otherwise entirely new, with Houdyshell as the Earl of Gloucester, a nobleman loyal to Lear, and Marvel as the power-mad Goneril, the eldest of Lear's three daughters. Gold's no-frills production—performed without raiment, in modern dress—has an original score by Philip Glass, with musicians moving about the stage.

Lear is not for the faint of heart, requiring stamina from cast and audience. The play is long (three-plus hours), fast and full of primal fury. "It's a meat grinder," says Marvel. In some cases, literally: Gloucester gets both eyes gouged out; most of the characters die horribly; everyone suffers. It's also filled with the rich, metaphoric language of Shakespeare—gorgeous to the ear, if incomprehensible to many modern listeners. People sit forward in their seats, says Houdyshell: "It's not easy. You have to work. I can hear the audience listening."

The overall and timeless message of Lear is to look past the surface—beyond rank, power, wealth and gender; the truth of people is in their heart and actions, not easy words. The prideful, self-righteous Lear and the credulous Gloucester catastrophically trust the wrong children: wicked Goneril and Regan in Lear's case (as opposed to his devoted youngest daughter, Cordelia); villainous, illegitimate Edmund, rather than virtuous, legitimate Edgar, in Gloucester's.

Newsweek spoke with Jackson, Houdyshell and Marvel a few weeks before the play's April 4 opening (the limited run ends on July 7). Laughter is frequent, exhaustion evident. During previews, the cast is continuing to rehearse before performances—seven a week until an eighth is added the week of April 8. "The first time I did an eighth performance in the U.K., the rest of the cast were waiting for me to die—they were probably disappointed I didn't," Jackson joked recently. Lear's energy saves the day. "It's immediate," she says now. "If you tap into that, it feeds you."

Glenda, do you see a difference between American and U.K. audiences?Jackson: Oh my God, are you kidding?

Houdyshell: How are they different?

Jackson: They're there! They roar! They leap to their feet. Mind you, in England, it's very different. We tend to look down our noses at America's obsession with standing ovations. A standing O for him? What'd he do that was so good?

But that's also the marvelous thing about working with American actors. They're so alive! I'm of an age where when I started in England the fashion for actors was to go, Oh God, is that my cue? Right, I'll put the crossword down. Here, it's a matter of life and death, isn't it? That's great to work with.

How would each of you persuade a young person, unfamiliar with or daunted by Shakespeare, to see King Lear?

Marvel: [Gestures to Jackson and Houdyshell] You're seeing two of the greatest actors, for one thing.

Jackson: Good God.

Marvel: It's also Shakespeare's greatest play.

Jackson: Some people say The Tempest is his greatest; I agree that it's Lear. The great excuse for Hamlet is youth, youth, youth. Lear is richer for being written from an older perspective.

Marvel: Hamlet is a solo journey. Lear is about the world. It's cosmic, metaphysical—it's everything. All the characters are heard and seen. That's something we're all proud of with this production: Everyone's point of view is valid and justified—to a point. [Laughs.]

Houdyshell: The reason great actors essay the role of King Lear more than once is because it has layers of meaning, which change as you age. You want to go away and come back to it. When you're working on any great piece of dramatic literature, a definitive thing is never possible; it's constantly evolving. I listen to Lear very carefully still, and for an actor, the evolution will never stop, through the last performance.

Jackson: You learn more about your own character from what the other characters say about you. It's so fucking genius.

Marvel: It's like a giant gold mine, this play. You keep digging out more.

Jackson: I can't get over the fact—well, I can—that Shakespeare wrote Lear, the Scottish play [Macbeth] and Antony and Cleopatra all in the same year—using bloody candlelight and quill pens!

Houdyshell: Another argument for seeing Lear is Edgar. His is the youngest voice in the play and the last one you hear: He's left to survive somehow, some way. I think that would resonate with young people questioning everything that has come before after many, many years of abuses. The world is in dire straits, and this play, among other things, maps out the journey towards that kind of destruction and decay.

Edgar's motives are ambiguous for much of the play. After being betrayed by Edmund, he disguises himself as a mad beggar and does seem to go a bit crazy. But he's also the play's final hero. His radical shifts can be confusing.

Jackson: These are people with very quick brains and huge, immediate responses! They don't plot. They find themselves in these situations and they react. They discover for themselves what they are.

Houdyshell: It's radical moments and awakening that keep unfolding. That's life, right?

Marvel: Edgar is an impossible part, but I'd love to play him. I'm endlessly fascinated by what's happening with his mind. Shakespeare understood something about mental health—that the trauma of abandonment in young people can create extreme psychic shifts. His experience is bifurcated; part of it is this desperate need to disguise, and part of it is a whole other landscape that his brain is functioning in. Shakespeare gives voice to mental illness in a way that rarely happens.

Jackson: But also Shakespeare's acknowledgment, through Edgar, that abject poverty is accepted—it simply isn't noticed. We do it now: How many people today are sleeping on our streets?

Comparisons have been made between Lear and Donald Trump.

Jackson: [Grimacing dramatically] Hardly!!

Yes, Glenda, he does see the error of his ways—eventually, after going mad—but the king we meet at the beginning is an extreme narcissist; he doesn't rely on counsel, fudges facts, rewards those who compliment him. When George III was king of England, Lear was banned because of George's insanity. If the Trump administration had such power, they might employ it.

Marvel: I guarantee you, Donald Trump has never read King Lear.

Houdyshell: That magnetic and corrupting draw to power—whether it's people who desire it for themselves or people who want to be close to it—is a human thing. Shakespeare is examining the universal, which is in all of us.

Jackson: I always think of Henry VIII; no one ever said no to him, which is very much the center of King Lear. It was the time when an absolute power was acceptable because, of course, it could carry you with it, or just as easily kick you out and kill you. And that kind of obeisance to power, however it's defined, hasn't changed in our world. It's still there.

Marvel: And it applies to Trump, North Korea, Russia.

When Shakespeare wrote his plays, female actors didn't exist. Women were played by teenage boys. It's about time, then, that the tables were turned.

Jackson: Well, exactly. But also, as we age, absolute gender boundaries go. I noticed that when I would visit old people's homes when I was in Parliament. The tension between men and women isn't necessarily different, but the boundaries fray.

Houdyshell: My initial approach to the role of Gloucester was, OK, what it is to be a father as opposed to a mother? And I found that there aren't that many significant differences. Love is love, and the parental bond is the parental bond. So I don't look at him as a man going through his journey, but as a human being going through it.

And it's quite a journey. To see the truth, Gloucester has to literally lose his eyes.

Houdyshell: Gloucester has many blind spots. [Laughs] And some of that, actually, is societal, in terms of the way in which he regards the legitimacy of his children. He has an awakening about that. He becomes a larger, richer person, and he discovers parts of himself that society, and positions in his society, had closed him off to.

Marvel: I've been thinking about the Book of John, when God calls out to Peter and says, Do you love me? And that is the question this play begins with: Lear dividing his kingdom based on how his three daughters respond to the question, Do you love me? And love is complicated, because love and admiration are two different things. When we admire someone, we lift them up; they're separate. When we love someone, we want to join with them. And this play begins with the misunderstanding of that question, and it devolves from there. It puts two people under a microscope—Lear and Gloucester—and it makes them examine that question of love versus admiration. Our society is so competitive—relationships with people, so often, are shaped by competition. Lear looks at all of that.

What have you learned from working with each other?

Jackson: That I have to learn my lines better. I've left both of them wondering, What the fuck is she not saying?

Marvel: It's funny because the conversations I've had with Glenda and Jayne—[to Glenda] we mostly talk politics and travel; [to Jayne] we talk philosophy and spirituality. We don't talk about acting. I haven't told you this, Glenda, but when I was a very young person, I saw you on PBS doing Strange Interlude. It was transformative. And so I've carried you with me.

Jackson: Sorry about that, girl.

Marvel: And I saw you, Jayne, very early, when I came to New York. So you both had a massive impact on me as an artist. It's been so lovely working with these women because we all grab our shovels and just get digging. I revere them, but we're the same.

Jackson: There is such support in that. We get up and do the bloody work!

Houdyshell: My first experience of seeing Glenda was also on PBS, doing Marat/Sade. I was 15, and I wanted to be an actor, but my experience of theater was limited. That performance was life-changing for me; it expanded my vision of what was possible—I didn't think acting could be that.

Jackson: Well, that was [director] Peter Brook, wasn't it?

For me, it was seeing Glenda in Women in Love when I was a teenager. I thought, That's the woman I want to be!

Jackson: She was a bit off in my book.

But that scene where you're dancing among the bulls, taunting them? Whoa.

Jackson: "Closer," said [director] Ken [Russell]. "Get closer!" They had huge fucking horns! He said, "You don't need to be worried about them. They're more frightened of you than you are of them." I said, "How do you know what I'm feeling!"

King Lear will be at Broadway's Cort Theatre through July 7. You can find tickets here.