For five years, the young man has worked the rolling mill that churns out slab after slab of high-strength steel products bound for auto mills and large construction sites across the country. His paycheck has risen slowly but steadily, and two years ago he bought a three-bedroom house in a solidly middle-class suburb for himself and his family. And though the steel industry now suffers from overcapacity and is consolidating nationwide, he has little fear that his job will be affected. The company he works for is huge and profitable, and the mill in which he works is state of the art.

Cai Jinrong, in other words, is living the great middle-class Chinese dream. The company he works for is Baosteel. The house he owns is in suburban Shanghai. And to hear U.S. presidential candidates tell it, to one degree or another, his relative success—and his company's and his country's—has come at the expense of his counterparts in the United States: lunch-bucket workers in industries like steel and auto and machine tools—the metal-bashing businesses that flourished in America after World War II and provided solidly middle-class lifestyles for a couple of generations of families.

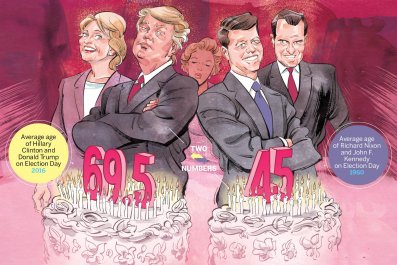

That is no longer the case. Manufacturing employed 17.1 million Americans in 2000; it employed 12 million at the end of 2013 (the most recent data available). Manufacturing wages have barely grown for nearly two decades now. And these realities have brought what may be a historic shift in U.S. economic policy: a fracturing of the free trade consensus that has prevailed since the end of World War II. Donald Trump, the Republican presidential front-runner, says he'd slap a 45 percent tariff on all goods imported from China (a position that has horrified executives at the American Chamber of Commerce in China, among others). Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton, whose husband signed the historic North American Free Trade Agreement when he was in the White House and presided over eight years of prosperity, has disavowed the Trans-Pacific Partnership—which was negotiated by the Obama administration while she was secretary of state, and which she once called the "gold standard" of trade agreements. Even among the also-rans in this political cycle, no one ever has a good word to say about free trade.

What's behind all this skepticism about free trade? The answer, according to several mainstream (and normally pro-trade) economists is China—or, to be more precise, China's 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization (heartily supported by the George W. Bush administration) and the subsequent economic ascent of what is now the world's second-largest economy. Among the most influential papers reshaping the received empirical wisdom about how labor markets adjust to trade shocks is one published in January by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which for decades has been at the core of establishment economic thinking in the United States. In the study, titled "The China Shock," authors David Dorn, David Autor and Gordon Hanson conclude that an "adjustment in local labor markets [has been] remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences [in 2001]. Exposed workers experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income. At the national level, employment has fallen in U.S. industries more exposed to import competition, as expected, but offsetting employment gains in other industries have yet to materialize."

In other words, the only benefit to the U.S. from the massive surge of Chinese imports—manufactured imports from China have risen from 4.5 percent of the U.S. total in 1991 to nearly 25 percent today—is the low price of goods sold at Wal-Mart and elsewhere. The costs in manufacturing communities throughout the U.S., however, have been substantial: "Our direct estimates," the economists write, "imply that had import penetration from China not grown after 1999, there would have been 560,000 fewer manufacturing jobs lost through the year 2011." They estimate the impact of Chinese imports accounts for approximately 10 percent of the job decline in manufacturing.

At the same time, Trump's assertion that China has gamed the international trading system (while the U.S. government has stood by "like chumps," as he once put it) does have some basis in reality. China has had 34 complaints filed against it at the WTO over unfair trade practices since 2001, behind only the European Union and the United States in that time frame. And while China has grown as a market for U.S. goods and services, the bilateral trade deficit between the two countries remains massive: a staggering $365 billion last year, the biggest bilateral deficit on record.

In the past, economic theory held—and reality usually bore out—that over time labor markets adjusted to the effects of foreign competition. A fair number of workers displaced would move to other industries, often in more economically vibrant parts of the country. This was especially true in the 1980s and '90s, when America's Sun Belt states grew their populations significantly and Rust Belt cities like Pittsburgh and Detroit saw workers flee.

Economists call this "the reallocation effect," and it is—"surprisingly," as Autor puts it—not evident when it comes to the time period coinciding with China's economic rise. "The reallocation of employment appears to be swamped by the overall adverse effect of the surge [in China's imports] since WTO accession in 2001."

There are, to be sure, other reasons displaced workers haven't been reabsorbed as quickly as they were in the 1980s, when U.S. trade deficits with Japan became a political obsession in Washington. The financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, which debilitated the economy, is one obvious reason, and other economists believe increased regulation over the past decade or more is another cause of wage stagnation and long-term unemployment.

It's not yet clear whether Chinese leaders in Beijing comprehend what a potentially profound shift in U.S. trade policy is in the wind. They tend to view the Trump campaign as a bit of a joke—and are said to be content to believe that Clinton is just saying what she needs to about trade to get elected; once she gets in the White House, "they don't think much will change," says one U.S. diplomat.

Perhaps so; perhaps not. President Xi Jinping is likely to be more enlightened after his visit to Washington for a conference on nuclear nonproliferation at the end of March. On the likely agenda for his talks with President Barack Obama was the possibility of a bilateral investment treaty between the two countries, which they have worked on for several years now.

But the notion that it will get done before the end of Obama's last term, and in the current political climate in the U.S., is fanciful. And the possibility that the free trade consensus in Washington is a thing of the past is all too real. If Beijing doesn't get that now, it likely will soon enough.