In the summer of 2006, a squad of U.S. military policemen deployed to Iraq, eager to join the war. They were tough kids, many from small, working-class communities scattered across the American heartland, who'd joined the military for many of the familiar reasons: post-9/11 patriotism, adventure and the hope for a better life when they got out.

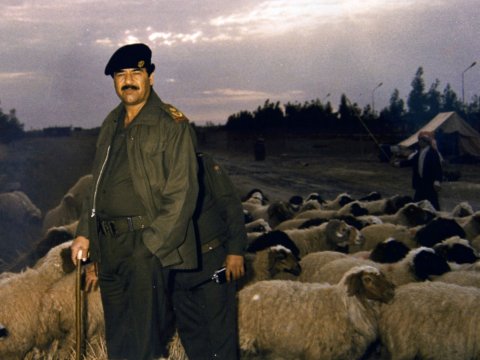

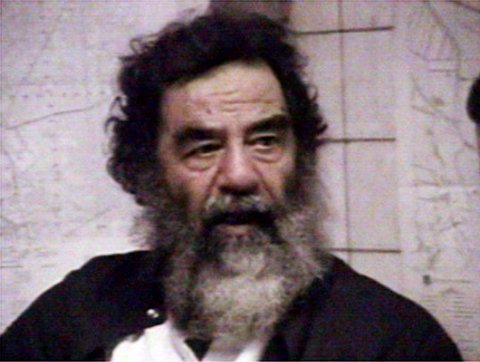

They were hard-charging and well trained, but nothing could have prepared them for the mission they were given a few months after they landed in Baghdad. They would be responsible for a "high-level detainee"—Saddam Hussein, the former president of Iraq. The brutal dictator had been deposed by a massive military invasion, then captured after nine months on the run. He was now the most famous prisoner in the world.

Upon receiving the news, a few of the MPs joked, "We should kill him." Some of them knew their new charge had once said, "I wish America would bring its army and occupy Iraq. I wish they would do it so we can kill all Americans. We will roast them and eat them."

What follows is an exclusive peek inside the walls of a palace turned prison, built to hold one man, and a tantalizing glimpse of the complex and improbable relationships that developed over the next four months these men would spend together.

Baghdad—September 2006

Specialist Steve Hutchinson was, once again, working nights. But this time, he was half a world away from the Midnight Rodeo in central Florida, where he'd been prying apart drunk brawlers. Just a few weeks before, he and his squad mates in the 551st Military Police Company—the Super 12—were given a top-secret mission: guard Saddam while he was tried by an Iraqi tribunal for some of the many atrocities he had committed during the two decades he ruled his country with a profligate brutality.

Hutch and the rest of his Super 12 team were ordered to not tell anyone about their mission, even their families. They weren't permitted to keep a journal, all their emails were monitored, and they were subject to random searches to make sure they weren't taking notes about what they were doing, seeing, hearing or even thinking.*

Hutch's first shift with his notorious prisoner began at midnight. The two of them were in the bowels of the Iraqi High Tribunal (IHT), a courthouse constructed just to try Saddam and his seven co-defendants for crimes against humanity. Beneath the courtroom was a row of subterranean cells—half-wall, half-plexiglass enclosed rooms that resembled the "interrogation room in a movie"—in which Saddam and several co- defendants were held when they were due in court.

The Super 12 called their own temporary lodging beneath the IHT courtroom "the Crypt." It was dark 24 hours a day because, at any given time, some of them would be sleeping, since their lives were now an endless loop of eight-hour shifts guarding Saddam. They had been ordered to maintain visual contact with him at all times to make sure he didn't harm himself or wasn't harmed by someone.

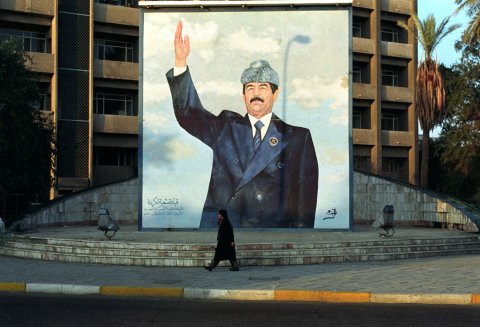

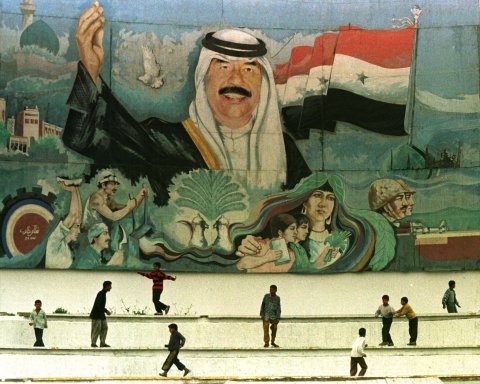

The IHT—housed in a former Baath Party headquarters building, a hulking, pillared structure—was established by the Americans who had toppled Saddam's regime with a massive invasion. The tribunal was modeled on U.N. war crimes tribunals while borrowing from Iraqi criminal procedure. The court had chosen to try Saddam for the killing of 148 Shiite residents of Dujail in response to a failed assassination attempt when he had visited that town in the early 1980s. This seemed to many an odd choice as the first crime to prosecute Saddam for, given the other, better-known killings for which he was responsible, most notably the chemical gas attacks against Iraqi Kurds during the Iran-Iraq War. Those attacks killed thousands, including women and children, in excruciating fashion.

On previous deployments at detention facilities, Hutch had been the Super 12's "screamer"—it was his job to let detainees know that no shit would be tolerated. "You give them that initial shock, where you stand in front of 'em, probably about an inch from their face, and scream out the rules and regulations," Hutch explained. "Your job is to establish that the guard has ultimate control." He knew he wasn't going to be screaming at this prisoner.

As Hutch eased into the old metal chair outside the cell, he could see that Saddam appeared to be sleeping comfortably. The man he had long thought of as a ferocious demon was now just a few feet away from him, snoring peacefully.

More nervous than he'd expected to be, Hutch reminded himself to remain vigilant. There were constant rumors that Iraqi insurgents would try to free Saddam, and he'd also been cautioned to watch out for an unbalanced soldier trying to kill the former dictator, either as an act of vigilante justice or to become famous.

Hutch began anxiously leafing through a graphic novel, Resident Evil—Code: Veronica , to pass the time. (Over the course of this deployment, he'd work his way through all the Harry Potter books and the Hunger Games series, so he would have something to discuss with his 4- and 6-year-old daughters when he called home.)

Suddenly, the silence was shattered: Ali Hassan al-Majid, one of Saddam's former top lieutenants, had begun praying. Ali—"Chemical Ali"— was accused of having helped mastermind a genocidal campaign that used both chemical and conventional weapons to exterminate Iraqi Kurds, who were considered a threat to Saddam's rule. One gas attack killed at least 5,000 men, women and children, perhaps 10,000. Through his systematic persecution of the Kurds, Chemical Ali may have been responsible for the deaths of more than 100,000 people.

Ali's praying jarred Saddam out of his dreams, and he was now mumbling his own prayers while still lying in bed. He seemed to be going through the motions, Hutch thought, without much feeling. Though the Baath Party Saddam had led was, in theory, secular, the dictator had launched a "faith campaign" in the 1990s designed to push Iraq in a more devout direction. He'd even donated blood regularly so that a copy of the Koran could be written in it.

Baghdad—October 2006

Whenever Saddam wasn't on call at IHT for court appearances, the Super 12 MPs guarded him in a bombed-out palace near the airport on a small island accessible only by drawbridge. The Super 12 nicknamed the island in this man-made lake "the Rock," after the Alcatraz prison movie of the same name.

The sprawling constellation of former government residences and palaces, of which this island was a small part, was where Saddam and his favored ministers had once enjoyed hunting outings followed by extravagant dinners. It was also where his son Uday had indulged in sadistic alcohol- and drug-fueled orgies. Taken over shortly after the invasion, it was now called Camp Victory, and it resembled a mini-America—it had a Burger King and a Subway and hosted a wide array of entertainers, from country star Toby Keith to professional wrestlers. (The soldiers were particularly fond of the scantily clad WWE Divas.)

The Super 12 had been instructed to avoid interacting with Saddam while doing whatever they could to keep him safe and happy. The U.S. leadership didn't want even the faintest suggestion that he'd been mistreated and figured that the more content Saddam was, the more smoothly his trial would go. At first, the MPs were careful not to engage him in conversation, limiting their interactions to a chilly "yes, sir" or "no, sir," but they spent 24 hours a day with him, and some thawing on both sides was inevitable.

Hutch, a veteran MP, knew it was a bad idea to grow close to detainees, and he was very wary of this prisoner. This was the man who, after all, had reportedly responded to a wife's request to free her husband—a government minister who had been jailed for offering a suggestion Saddam did not like—by sending him home to his wife in a black canvas bag, chopped into pieces.

For these young soldiers, guarding Saddam was like visiting the zoo to watch a lion that, though deadly, rarely does anything but sit, eat and sleep, only occasionally deigning to walk across the cage to thrill his audience. But their initial hypervigilance naturally ebbed as one uneventful day blurred into the next. A few weeks into their mission, Hutch and Paul Sphar were sitting across from Saddam in the outdoor rec area near his cell. It was just 15 feet long and 7 feet wide, enclosed by tall concrete walls topped with barbed wire, but it offered something of great value to a prisoner who spent most of his time in a windowless cell: a glimpse of Baghdad's blue skies.

Joseph**, the interpreter, sat next to Saddam on plastic patio furniture chairs, on one side of a small plastic table; Sphar and Hutch sat across from them. Saddam and Joseph puffed on Cohibas as they chatted like two retirees at the local diner catching up on the local gossip. Hutch and Sphar couldn't decipher their Arabic, but Saddam, as always, seemed shockingly relaxed for someone on trial and facing a death sentence. This calm was perhaps due to the fact that, for the first time in decades, he was in a protective cocoon, insulated from the internal and external threats that had been a constant worry from the moment he had seized power. He had his nation gripped in fear and paranoia, but that fear ran both ways—Saddam knew thousands of Iraqis would happily sacrifice their lives for the chance to plunge a knife in his chest or cut his throat while he slept.

Saddam appeared to derive immense satisfaction from simple pleasures, like smoking his cigars. He would carefully—almost theatrically—pull a Cohiba from the emptied wet wipe box he carried them in. Then he'd light the cigar, savoring every inhalation before exhaling. (He proudly announced to the Super 12 that Fidel Castro got him hooked on cigars.)

Joseph suddenly turned from Saddam and spoke to Hutch: He wants to know where you're from, your nationality.

Hutch was puzzled. Tell him America.

No, no, before that.

Well, I guess from Europe...

No, no, there is more, Saddam said, showing that he'd been following the entire exchange. This was one of the first indications the Super 12 got that his English was surprisingly good, although they would learn that he employed it only strategically.

Hutch was unsure what Saddam was asking. What does he want from me?

He just wants to know your heritage.

Hutch now realized Saddam was curious about his ethnicity, since his complexion had darkened considerably from constant exposure to the relentless Iraq sun.

Hmm, well, I am also part Native American.

Saddam quickly put one finger behind his head like a feather and another in front of his mouth, mimicking an Indian war cry. Hutch burst into laughter.

Saddam's primitive radio was playing quietly in the background. Though he'd been offered access to more modern modes of entertainment, like a portable DVD player, he preferred the old radio, with its antennae grasping to pull signals from the desert sky. He'd usually switch between Arabic channels and American pop music, and one of the young MPs noted that he'd always stop tuning if he stumbled across a Mary J. Blige song.

Saddam opened a book he'd laid on the plastic table. He flipped through it as the two soldiers looked over his shoulder, studying each page carefully through his reading glasses, occasionally pausing when a picture seemed to trigger a memory. He pointed to a picture of himself as a young schoolboy. The fact that he'd even been able to attend school was the stuff of Baath Party mythmaking. A young Saddam, the story went, was ambitious and desperate to escape his stepfather's abuse and a dismal future as a subsistence farmer in the dusty and violent backwater of Awja. One night, he snuck out of his mother's mud hut and made his way along desolate, bandit-infested trails to his uncle Khairallah Tulfah's house in Tikrit. The uncle was a former army officer and Iraqi nationalist who'd spent time in prison for participating in a rebellion against the British. He took Saddam in and got him into a school.

Headmaster expelled me when I was young! Saddam said, still squinting at the picture. He explained that the headmaster had enraged his uncle by kicking Saddam out of school, which his uncle viewed as an affront to the entire family.

Headmaster paid for this insult. When my uncle heard, he gave me a gun, told me to make sure they let me come back!

Saddam sipped his tea, took a puff on his cigar, then sat back and smiled, letting the soldiers imagine the fate of that unfortunate headmaster.

Baghdad—October 2006

Vic, we're gonna move tonight.

"Vic" was short for "very important criminal," and a few of the guards would occasionally call him that, though most stuck with "sir." Specialist Adam Rogerson had received word that they had to deliver Saddam to the IHT late that night. Rogerson wanted to give Saddam plenty of notice so he'd have time to pack his bags.

Saddam began his pre-movement rituals. First, he went outside and made sure to water his plants—just weeds—growing in the small plot of soil in his rec area. Next, he began to pack his olive-green, Army-issued duffel bags. He'd carefully make sure that items he expected to need first were near the top. His suits, which the Army regularly had dry-cleaned, were then carefully placed in garment bags by one of the MPs.

The last things he packed were his notepads, pens and that wet wipe box full of cigars, which he kept near the top of his bag for quick access when he arrived in court. A few MPs stepped forward to help carry his heavier bags, as well as the garment bag with his suits. When Hutch reached over to help Saddam with one of bags, he strained to lift it and joked to Saddam, "What the hell, did you stuff Ali in this bag?"

Saddam laughed heartily, and when he arrived at the IHT, he shared the joke with Chemical Ali.

Baghdad—Late Fall, 2006

Dressed in his dishdasha and clutching his prayer beads, Saddam paced in his outdoor rec area, silently mouthing a string of words. Hutch later recalled that when Saddam walked back and forth like this, mumbling to himself, "you'd think he'd lost his mind if you didn't know him." Sometimes his cadence and mannerisms suggested to the Super 12 that he was rehearsing things he planned to say in court. He was awaiting a verdict in the Dujail trial while working on his defense against charges of genocide for the savage Anfal campaign against Iraqi Kurds during the Iran-Iraq War. Saddam must have suspected that his behavior appeared odd, because he'd sometimes look up, catch his guard's eye and offer a sheepish smile.

Hutch was absentmindedly flipping through one of the People magazines he'd become hooked on during this deployment when he noticed that Saddam had stopped pacing and was looking at him. Sir? Hutch said, anticipating a request, but Saddam just wanted to talk.

Me and Barzan, we used to fish right near here, you know. Oh, very big fish there, not so many there, Saddam explained, describing the various fishing holes in the nearby lake.

The MPs knew those fish could grow quite large. In fact, American soldiers in Baghdad took to calling the hulking carp "Saddam bass" after hearing rumors that he'd stocked the lakes with them. As with most stories surrounding Saddam, this one had a dark side. The Super 12 heard that Saddam's henchmen dumped the bodies of people they'd shot into that lake, which caused the large fish to develop a taste for human blood.

Even with Saddam now in prison and on trial, gruesome, widespread violence wracked Iraq. Now, instead of regime opponents, it was victims of Iraq's worsening civil war who were dumped into the water. Hutch once fished a "floater" out of the lake, the decomposing corpse disintegrating in his hand as he struggled to retrieve it.

As sectarian death squads ramped up their ethnic cleansing of Baghdad neighborhoods, ghastly discoveries across the city became routine—a dozen corpses, for example, caught in the metal grates intended to block debris from the lake getting into the Tigris River. The victims had been bound, blindfolded and shot in the head. After three years of escalating violence in Iraq, such macabre finds were commonplace.

Baghdad—December 2006

The cold December air blew in over the lake, gusting up against the walls of Saddam's former palace, and now his prison. Overnight, temperatures had dropped to just above freezing.

Saddam seemed remarkably placid, even though he had been sentenced to death for the crackdown at Dujail just a few weeks before. He and his guards knew that his execution day was fast approaching, barring a successful appeal, which no one expected.

As Rogerson sat outside with Saddam, the man President George W. Bush had declared was part of an "axis of evil" said, You want to sit by the fire with me? Saddam gestured to a plastic chair near the space heater he liked to call his "fire." He had a thing for naming inanimate objects, referring to the small, rundown exercise bike he would ride before his daily medical checks as his "pony."

Rogerson had grown up in Cleveland, so he was inured to harsh winters, but he happily accepted this little bit of shared warmth.

Saddam fired up one of his large Cohibas, the smoke from each puff wafting up gently into the night sky. Rogerson was craving a cigarette, but he and his fellow guards weren't allowed to smoke while on duty. Instead, he opened a small package his wife had sent from back home in Ohio. In it were some candles she'd purchased at Walmart. Rogerson noticed that Saddam seemed intrigued.

My wife has been sending me these candles.

I see that. What do you do with them?

Actually, I don't really need them, Rogerson said, laughing, but I suppose I can use them to make our living area smell better. You know how it is when a lot of guys spend so much time together—it can smell pretty nasty.

Both men chuckled. Rogerson handed one of the scented candles to Saddam so he could take a closer look.

Do you think maybe I could have one?

Sure.

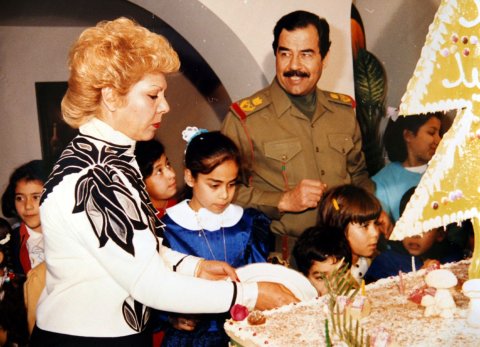

Thank you, my friend. Saddam then picked up a pen and began to carve Arabic words into the candle. After a few minutes, he said, I've written a poem for my daughter, then asked Rogerson to give it to the Red Cross for delivery to her.

A few weeks later, it was Christmas Day, and Saddam was at the Rock, awaiting a decision on his appeal. There were few decorations to mark the holiday season, aside from a small Christmas tree someone had set up in the Super 12's computer room. Little else distinguished this day from a normal day, save for a few extra care packages arriving in the mail. Rogerson had been thrilled to open an especially large package that contained enough Cap'n Crunch Christmas cereal for the entire squad.

Saddam was outside, near his "fire," sitting under the one outdoor light, pen in hand, intently focused on another of Rogerson's candles. After laboring at his task for a while, Saddam looked up at Private James Martin**, who was trying to stay warm on the other side of the rec area.

This is for my wife.

Really? Martin was surprised, because Saddam rarely volunteered information about his wives. Whenever the subject of family came up, he generally steered the conversation to his children.

Yes, we have a tradition. Every year on the Christmas holiday, we light a candle. I'm writing a poem for her on this one.

Saddam's unexpected Christian holiday tradition wasn't the first time he'd displayed a surprising affinity for something related to Christianity. He'd recently asked if he could watch The Passion of the Christ. After the film was over, Saddam said he was angry at the way the Jewish characters in the movie had treated Jesus. He maintained that "Iraqis would have treated him better." He added that The Passion of the Christ was the best movie he'd ever seen.

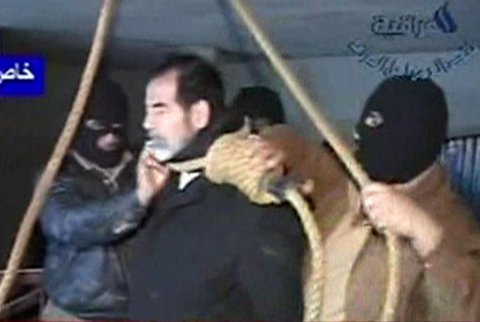

The next day, December 26, 2006, Saddam's appeal of his guilty verdict for the Dujail massacre was denied, which meant he would soon be hanged.

The rejection of the appeal didn't surprise the Super 12. They'd heard some of the horrific testimony about his chemical gas attacks on the Kurds. Still, they struggled to connect that brutality with the pleasant man they had dealt with 24/7 for the past several months. "When I'd see the trial going on, and what he'd done to his people," Rogerson later recalled, "I'd be like, 'Holy shit, there's a shitload of dead people, he just killed an entire city…. But then I'd see him, and I never looked at him like that, because he wasn't that person with me…. He was more like a grandpa."

Saddam wrote one more candle poem that Christmas, this one for the Super 12. Translating from Arabic, he told them it said he wished they could be back home in America with their families to celebrate Christmas instead of guarding him in Iraq.

Baghdad—December 30, 2006

It was time.

The old man slipped into his black pea coat, then placed a dark fur hat on his head to protect against the predawn chill. This night was one of the coldest the Super 12 team had endured in Iraq. Six of them stood outside the bombed-out palace, dressed in "full battle rattle," clunky in their Kevlar vests and helmets with the mounted night-vision goggles. They each carried a full combat load of hundreds of rounds of ammunition.

As they scanned their surroundings for anything out of the ordinary, the other six soldiers led their prisoner into an idling Humvee for the short ride to the chopper landing zone.

The silver-bearded old man moved deliberately, almost proudly, straining to maintain an upright posture despite his bad back. Nearby, two Black Hawks waited, rotors already a blur, kicking up clouds of sand and gravel. The greenish glow of the soldiers' night-vision goggles added to the disorienting maelstrom of sound, temperature and light.

The six MPs clustered around the old man led him into one of the Black Hawks, ducking under the swirling rotors and then gingerly climbing aboard, being careful not to trip, since their night-vision goggles impaired their depth perception. They were joined by two medics and an interpreter, who added welcome body heat to the cramped fuselage. Once the first group had piled on board, the remaining MPs quickly boarded the second Black Hawk.

The choppers then lurched skyward, beginning their short flight to an Iraqi installation in Baghdad's Shiite Kadhimiya district. A brief look of fear flashed across the old man's face when the chopper bounced a bit in some rough air. He'd always been a nervous flyer. Otherwise, he was stoic and silent.

As soon as the choppers landed, the soldiers ushered Saddam to a waiting "Rhino," a massive armored bus. The soldiers then piled in, as did the interpreter. It was eerily quiet as the 13-ton Rhino rumbled across the compound. There was none of the casual banter that usually filled the air on such missions; just silence.

After a short ride, it was time to hand over their prisoner. Saddam rose from his seat and carefully straightened his pea coat, making sure it wasn't rumpled from the brief ride. (One of the soldiers had worked it over with a lint roller before they'd left his cell.)

Saddam then began to walk slowly from his seat near the back toward the Rhino's front door. As he made his way to the front of the dimly lit armored vehicle, he stopped to grasp each of his American captors and, in a few cases, whispered some final private words.

Some of the soldiers had tears in their eyes.

When the old man reached the front of the vehicle, he turned to them one last time and said, "May God be with you."

He then bowed slightly and turned toward the door.

*A note on the reporting: This account is based on nearly 100 interviews the author conducted with U.S. and international government officials, soldiers, scholars, spies and lawyers with unique insights into Saddam's capture, imprisonment and execution, as well as interviews Army historians conducted with his guards a few months after the execution. Because the soldiers adhered to guidance surrounding this mission's secrecy, there is no real-time documentary evidence, and therefore it was impossible to pin down precise dates for some of the events described here. Also, since this account is drawn from memories, the dialogue is not in quotes, except for the few occasions when several participants had an identical memory of a conversation.

**Pseudonyms have been used for the soldiers who were not interviewed for the book in order to protect their anonymity, as well as for Saddam's interpreter.

This excerpt is from The Prisoner in His Palace: Saddam Hussein, His American Guards, and What History Leaves Unsaid, by Will Bardenwerper. Copyright © 2017, Will Bardenwerper. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc.