Updated | Feral cats roam the deserted, rubble-strewn streets. The rusted skeleton of a burnt-out car sits outside a house used as a bomb factory; inside, the kitchen floor is littered with mortar parts and metal shavings. Almost a month after Iraqi special forces reclaimed Ramadi from the Islamic State militant group, Iraqi troops are still patrolling the streets and clearing booby-trapped buildings.

"Real estate office" reads a hand-lettered metal sign featuring the now-familiar logo of ISIS, an organization in retreat in Iraq but far from defeated. The Iraqi special forces officers with whom I'm on patrol fling the sign onto the empty street. In the seven months that it held Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province, ISIS financed itself in part by selling off public property, according to residents. In some places, it punished former police officers by forcing them to buy back their own homes.

After the catastrophic collapse of Iraqi security forces in the face of the ISIS onslaught in 2014, recapturing Ramadi in late December has clearly restored confidence.

"Iraqis are conquering everywhere now," says Sergeant Major Hussein Youssef, who holds his rifle aloft as if he is posing for a recruiting poster. Youssef, a 26-year-old from Nasiriyah in southern Iraq, has been wounded four times and spent a total of six months in the hospital since he joined the special forces six years ago. (A few days after we meet, shrapnel struck him in the leg as forces retook the neighborhood of Sarajiya, one of the last ISIS holdouts on the eastern outskirts of the city. As an engineer tried to dismantle a roadside bomb, two others next to it exploded.)

In a house on the edge of Ramadi that serves as a tactical operations center, Major General Sami al-Aridhi, 3rd Division commander of the Iraqi Special Operations Forces, gives his go-ahead for a U.S. airstrike on the edge of the city. The radio crackles with grid coordinates as an Iraqi colonel at the center, in barely accented English, answers an Australian officer who is part of the U.S.-led coalition at Taqqadum air base, about 24 miles southeast of Ramadi. The colonel tells Aridhi the target is 12 armed men on the outskirts of Ramadi in an area where there are no friendly forces. Aridhi agrees to the U.S. airstrike. "Sometimes we locate the targets, and sometimes it's the Americans, but they don't hit it until they get our permission," says Aridhi, a former Iraqi army commander who was asked to return to duty in 2008.

The Iraqi colonel is from a different generation. A full colonel at the age of 34, Arkan spent four years receiving training in the United States. He does not want to give his last name or be photographed, but his relaxed, self-assured demeanor, as well as his black trousers and shirt and desert boots, are reminiscent of the American special forces. He says such training has continued in Iraq, and it's paying off. Iraqi security forces, Arkan says, are certainly capable of succeeding against ISIS. "It's not even a matter of opinion" he says. "We're doing it on the ground. We just took over a city."

It was not easy. More than 40 special forces troops and several hundred regular Iraqi army soldiers were killed in this latest battle for Ramadi. Special forces commanders say they killed around 130 ISIS fighters in the city and that about 180 civilians were killed in retaking the city—most by ISIS snipers and explosives laid by the group. As Iraqi troops approached the city late last year, ISIS detonated trucks packed with tons of explosives on bridges across the Euphrates River to keep the troops from advancing. Digging in for a fight, the militants laid explosives throughout the center of the city, connecting bombs to the wiring of houses and laying trip wire under carpets. "Iraqis have a lot of experience in war, but we've never seen these methods of fighting," says Aridhi, adding that almost all the buildings, even hospitals, were rigged with improvised explosive devices.

As the special forces troops advanced in Ramadi, they evacuated almost 4,000 civilians, whom they say ISIS had herded from district to district to use as protection against airstrikes. Medic Zuhair Jameel al-Said says he was able to lead hundreds of women and children to safety—except for one. As the troops were directing families onto a road that engineers had cleared of explosives, a bomb exploded in a house, scaring a small boy, who started running. When his mother raced after him, an ISIS sniper shot her in the chest. "She was six months pregnant," Said says. He put her in an ambulance, gave her oxygen and tried to keep her heart going, but he didn't know how to insert a chest tube that would have evacuated the blood from her lungs. She died before reaching the clinic. "We lost the mother and the baby at the same time," says Said, who sobbed when she died.

The Iraqi special forces found that the city had been divided into sectors. Fighters from Southeast Asia held one area, for example, and Russian and Chechen fighters had control of another neighborhood, one where ISIS leaders reportedly used to live. In some areas, ISIS bombs, Iraqi artillery and U.S. airstrikes had leveled almost entire city blocks.

The special forces troops say they are fighting to save Iraq. "We have Muslims, Christians, Yazidis, Kurds, Turkmen," says one noncommissioned officer, referring to most of the religious and ethnic groups in the country. But the ISIS takeover of large parts of Iraq has again laid bare the ethnic, tribal and sectarian fault lines that have been widening since President Saddam Hussein was toppled in 2003.

After the victory in Ramadi, the national police website featured a video of policemen beheading a captured ISIS fighter. In another photo, a fighter was hanged from the ceiling. The images were removed after complaints from Western officials.

At the destroyed police headquarters in Ramadi, glass has been punched out of the window frames, leaving shards like broken teeth. Lampposts lean into the rubble of concrete and twisted steel bars. Police Constable Mazen Adel says the new national police unit he joined fought with the special forces to retake the city and are staying to hold it. The government recruited 2,000 Sunni fighters from Anbar to play a supporting role in the battle of Ramadi. Another 4,000, including Adel, will become part of the new police force formed as an alternative to the widely distrusted Shiite-dominated federal police.

"There will never be reconciliation. We will completely crush them," Adel says of the former ISIS supporters seeking amnesty, using the Arabic acronym for the group. "The people who support Daesh have no place in Anbar."

Ghost Soldiers

The fall of Ramadi to ISIS in May 2015 was more than just a military setback. Iraqi security forces had abandoned the city, leaving tanks, artillery and weapons behind, prompting a parliamentary inquiry, as well as accusations from the U.S. defense secretary that Iraqi forces were unwilling to fight. That followed the collapse and retreat of two Iraqi army divisions in Mosul in the face of an ISIS onslaught in 2014. Widespread corruption—many officers allegedly bought their commissions to be in a position to demand bribes, and others profited by selling supplies meant for the troops—proved fatal when the army was faced with an actual enemy.

When ISIS swept through the country and the U.S. didn't immediately step in, Baghdad turned to Iran for weapons, ammunition and military support. Iraq's most revered Shiite cleric called on all able and willing Iraqis to fight the militants, creating the Popular Mobilization Forces—a combination of former militiamen and volunteers who have led the fight in central Iraq. Hundreds of PMF troops, acting under nominal command of the Iraqi government, have been killed, and several thousand wounded. But Anbar and its Sunni population have been largely off-limits to Shiite fighters of the PMF.

Retaking the Anbar provincial capital, an ordeal described by one U.S. commander as "tremendously slow" and "intensely frustrating," has strengthened the resolve of Iraqi security forces. Still, "they move in fits and starts," says U.S. Marine Corps Brigadier General William Mullen. "They move for a couple of days. They stop for a couple of days. After six months of 'Why aren't you moving today?' it was 'OK, we really need you to keep moving.'"

Mullen describes their victory in Ramadi with almost no involvement of the Shiite militias or the PMF as a game-changer. "When they first started doing this, they didn't think they could do it, and at points it got very difficult," he says. "We provided significant strikes for them, but the actual fighting on the ground, the wounding and the dying, was all done by Iraqis."

Problems remain, however. One Iraqi army division commander in Ramadi was fired during the campaign for refusing to advance, and Western military officials say systemic reforms in the Iraqi military forces are still needed. The U.S. and U.K. spent years training Iraqi forces and reconstituting an army that had been disbanded after Hussein was toppled. When U.S. forces pulled out in 2011, the most effective training by advisers embedded within the units ended. U.S. commanders say they have seen the difference with counterterrorism troops that maintained a connection with U.S. forces. "All training is perishable," says Lieutenant General Sean MacFarland, the U.S. commander of the anti-ISIS coalition in Iraq and Syria. "That's why those brigades, when they were attacked by the enemy, never gave ground, and they held their own in almost every case. We will do that as we move north, and we saw the power of that."

Iraqi army Brigadier General Yahya Rasool, who is the defense ministry spokesman, says bravery and loyalty are hard to teach. "How can I persuade my soldiers to die without hesitation?" he asks. "That is the art of leadership."

Rasool's cellphone ringtone is the Iraqi national anthem. In his office at the Defense Ministry in Baghdad's Green Zone, an ad for the Iraqi security forces airs on state-run television, showing an Iraqi soldier kneeling after breaking the padlock of a church in Mosul. "The bells of Mosul will ring again," the public service announcement intones. Rasool says the defeats of 2014 and early 2015 caused many Iraqis to lose faith in the army. "After the collapse in Mosul and Salahadin, and also in Ramadi and other areas in Iraq, there was mistrust between the Iraqi people and the Iraqi army," says Rasool. "The liberation of Ramadi restored trust between the Iraqi troops and the Iraqi people."

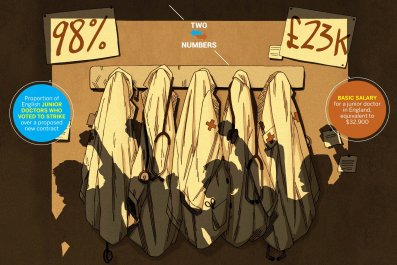

But the special forces and the retrained brigades are an island in what many U.S. and Iraqi officials still consider a sea of dysfunction. U.S. and Iraqi officials widely blame former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki for installing unqualified military commanders whose main claim to the job was personal loyalty. Around 40,000 "ghost soldiers" on the government payroll, who either didn't exist or never showed up for duty, have been eliminated, but some Western military officials say tens of thousands more salaries are still being paid to nonexistent personnel both in the army and the PMF. Coalition officials say key army divisions are at less than 30 percent strength. "On the very senior levels, I think there has been a tightening, but…the corruption in the ranks still exists, [and] the understaffing in the ranks still exists," says a senior Western official.

There are currently 3,500 U.S. troops in Iraq, most involved in training, advising and assisting Iraqi security forces, with an unspecified but increasing number of U.S. special operations forces more actively involved on the ground with Kurdish forces. About 19,000 Iraqi soldiers have now gone through coalition training in five military bases across Iraq. At Besmaya, north of Baghdad, Iraqi army companies trained by coalition advisers are put through simulated battles with live fire—aimed at giving them the confidence to stay out on the battlefield and the skills to survive. While most of the six- to nine-week courses focus on training as basic as how to hold a rifle, more specialized courses teach combat engineering and battlefield medical skills.

U.S. Ambassador Stuart Jones says when Ramadi fell to ISIS this past May, the U.S. was unfairly blamed for a failure of leadership and a lack of support. "This represents the reversal of that," Jones says. "It vindicates the U.S. strategy of providing air support…. A lot of the units involved in retaking Ramadi were trained by the United States."

The Militia Conundrum

While few dispute the need for the former Shiite militias in 2014 to prop up the weakened Iraqi security forces, now that ISIS is in retreat, the major question is whether they will willingly be disbanded once the battle is over.

"We have a lot of different groups out there on the battlefield," says MacFarland. "A lot of them are pursuing their own agendas. Some of them are pursuing agendas that are aligned with our agenda, and what we try to do wherever possible is get some sort of synergy between them and us."

Rasool, who worked alongside American troops fighting the Mahdi Army in Sadr City in 2008, acknowledges the inherent tension between the influential Iranian-backed members of the PMF and the United States, as well as the fluidity of armed Iraqi groups. The Sadrist forces that fought against the United States have now become a mainstream political movement. Leading members of the PMF, including Kataib Hezbollah and Asaib Ahl al-Haq, have been blamed for attacks against U.S. forces while they were in Iraq and have pledged to attack any American ground forces. "There is a sensitivity by the Popular Mobilization Forces to the [U.S. presence in Iraq]," says Rasool, adding that the PMF blames the U.S. for a friendly fire airstrike last year that killed some of its members. The U.S. has denied hitting any PMF forces and says only Iraqi aircraft were conducting strikes in those sectors. But concern about accidentally bombing Iranian-backed fighters has imposed strict boundaries on where the U.S. is willing to operate in Iraq.

At the command center responsible for coalition operations in Baghdad and Anbar, Mullen presides over a room of American and other coalition officers, as well as Iraqis. Walls of screens show intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance images beamed from drones and other aircraft to enable targeting. One of the screens is focusing on a Humvee in ISIS-held territory ahead of Iraqi forces moving down the Tharthar canal in Anbar province. Mullen says his main aim is to ensure "the people we are hitting are the enemy—not civilians, not Iraqi soldiers, and most importantly they're not PMF.

"If we hit them, we'll never be able to convince them that it was an accident, so that's one of the reasons why we generally don't provide support in those areas," says Mullen, a Marine commander in Fallujah during the battle of 2004 and calmer days in 2007 and 2008. He says the problem in keeping track of PMF forces is "they don't report where they are."

When ISIS swept south in 2014 and 2015, seizing towns and coming within 40 miles of Baghdad, it was the PMF that largely halted the advance. The largest of the roughly 30 groups under the umbrella of the PMF began as Iran-based militias to fight Hussein, such as the Badr Organization led by Hadi al-Ameri. The others include smaller groups not under clear control of any official authority. All have been accused of human rights abuses, including preventing Sunni villagers from returning to their homes and conducting reprisals after attacks on Shiites.

"I don't care if the West approves of us or not," says Ameri, whose visage has started to appear on billboards in Baghdad, with some showing rousing scenes of him on the battlefield with Iranian Quds force leader Qassem Soleimani. He denies that fighters under his command are committing human rights crimes. "[U.S. President Barack] Obama was sleeping—he had not woken up for four months until ISIS arrived near Erbil…. If we counted on the Americans, then ISIS would control Baghdad and all of Iraq. Should we be defeated so the West approves of us?"

Known as a gifted politician, Ameri says he prefers to talk about the present rather than any ambitions he has for higher political office. "The Americans are standing with the Saudis and with our enemies," he says. "Very frankly, we are looking for friends: Iran is a friend, and we are looking for another friend—Russia, instead of America." Ameri adds that he and his allies are also reaching out to China. "Let's talk about the end of ISIS, and then we will talk about the end of the PMF."

Though only specially recruited Sunni members of the PMF took part in the Ramadi assault, the group's wider influence is clear. Southwest of Baghdad, the road to Najaf and Karbala passes the renamed town of Jurf al-Nasr (Victory Cliffs), largely deserted of its former Sunni residents. Neon green calligraphy flashes "Allahu akbar" from a mosque near the road, illuminating the yellow flag of Kataib Hezbollah, which fought off ISIS in the area in October 2014. The highway is also the only truck route to Ramadi. An Iraqi special forces convoy of armored vehicles is made to wait for over an hour at a checkpoint while the young Kataib Hezbollah officer determines whether it should be allowed to proceed.

Ameri says the PMF has a responsibility to stop the smuggling of ammunition and other supplies to Fallujah, which ISIS still controls. But Western officials say Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi and even Ameri struggle with the renegade nature of the group. For example, when World Bank reconstruction funds, partly provided by the U.S., were allocated for Tikrit, the PMF stole two generators powering a water treatment plant, Western officials say. They were returned only after the U.N. threatened to freeze further funds.

"This is not working the way it is supposed to work," says one senior Western official. "There is a level of national government and oversight that is acknowledged, but it is difficult to enforce."

Money Talks

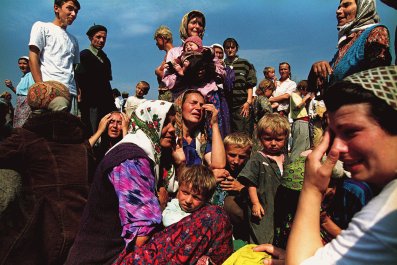

Ramadi, which had around 250,000 residents before ISIS took over, is now deserted. There is no electricity coursing through the hanging electricity lines, no water running through the pipes. And with Iraq suffering its worst financial crisis since 2003, there are no immediate prospects for raising reconstruction funds or enabling the civilians driven out by ISIS to return home. The last residents evacuated from the provincial capital are now largely in desolate camps in the former lakeside resort of Habbaniya and Amariyat al-Fallujah near the outskirts of Baghdad.

The war against ISIS has coincided with an unprecedented economic crisis that Western officials worry will prompt riots if Iraqi government payrolls can no longer be met. The plunge in oil prices and the cost of the war have led to monthly deficits of more than $2.5 billion. Finance Minister Hoshyar Zebari says the country, in part with U.S. financing, has covered the basic costs of the military campaign. He says Iraq plans to refloat a $2 billion international bond issue this year to raise funds. Other measures include reducing subsidies on fuel and electricity, cutting the bloated civil service and implementing customs duties—all controversial in Iraq.

"I'm honest with people," says Zebari. "I'm alerting them that this year is difficult. Unless you change, you won't be able to get your salaries. We have to educate people to make them aware that they cannot continue the way they used to."

While foreign aid has come in to help reconstruct Tikrit, which was recaptured last April, there is none in the pipeline for Anbar, where 1.1 million of the province's 1.6 million population have been displaced. "Ramadi needs international effort to rebuild," says Anbar Governor Sohaib al-Rawi, who is still based in Baghdad. He estimates between 20 and 80 percent of Ramadi has been destroyed, depending on the neighborhood, including the electricity grid, bridges, hospitals and schools. He says of an estimated $20 billion repair bill, "not a single dollar has been pledged so far."

Without the money that has traditionally eased reconciliation and pacified tribes, the future of some areas recovered from ISIS looks precarious.

"The liberation of Anbar is the beginning of partition of the region and the beginning of the partition of Iraq and the beginning of redrawing the map of the area," says former parliamentary speaker Mahmoud al-Mashadani, head of a largely Sunni bloc in parliament. Mashadani, like many Iraqis, believes the United States deliberately fostered ISIS to destroy Iraq. "If they had given even medium weapons to the tribes, this would not have happened," says the politician, who says he was jailed twice by Hussein and once by the American forces. But he also blames the Sunnis themselves.

"There is widespread injustice in Iraq, and that has negatively impacted the Sunnis," he says of the Shiite-dominated government. "But the Sunnis are also to blame. They have a responsibility, given their lack of participation in the political process."

During the fight against Al-Qaeda, the alliance between Sunni tribal leaders and U.S. forces relied largely on discretionary funds dispensed by the U.S. military—most often suitcases of cash. With the expiry of a status of forces agreement in 2011, the U.S. military in Iraq has neither the same authority nor the money to buy alliances. Many of the tribal leaders who profited most from the U.S. funds have sat out of the Anbar battle, observing from Iraq's Kurdistan region, Jordan or Qatar.

The fighters in Ramadi say ISIS is a much more formidable enemy than its predecessor, Al-Qaeda in Iraq. "Before, we cleared the city with local fighters and defeated Al-Qaeda, but now ISIS is not only in Iraq—it is in Syria," says police Constable Mohammad Ali Nauman, a former technical college student who joined the force two months ago. "The tribes are not as strong as they were in 2007 and 2008. The leaders are looking out for their political interests and not the interests of the people."

MacFarland denies that the funding empowered corrupt local leaders without a legitimate traditional power base. He says when he left Iraq in 2007, Ramadi was one of the safest cities in the country. "The sheikhs are the sheikhs," he says. "They all come together for a common purpose. Who are the right sheikhs, who are the wrong sheikhs? Who are we to say?"

The Next Fight

The victory in Ramadi frees tens of thousands of Iraqi troops to move farther up the Euphrates into western Anbar, toward the Syrian border. But first, Fallujah, to the southeast, remains in ISIS hands. As has been the case since 2003, the toughest fight in the deeply conservative tribal province is expected to be there. Anbar's biggest city, Fallujah was the site of the fiercest clashes with U.S. forces, seen as foreign occupiers after they toppled Hussein and then stayed in Iraq.

Using sweeping anti-terrorism laws over Prime Minister Maliki's eight years in office, his security forces replicated some of the most contentious U.S. military practices, arresting hundreds of men at a time in villages accused of sympathizing with Al-Qaeda and later ISIS. His markedly sectarian government went further, holding thousands of Sunnis for years without charge and sentencing hundreds to death based on what human rights groups say were coerced confessions. Many Fallujah residents initially welcomed ISIS.

In a measure of how difficult the fight there is expected to be, Iraqi military officials are talking about surrounding Fallujah to cut off ISIS supply lines rather than immediately retaking it. Isolating the city would also risk starving the civilian population.

As for Mosul, in northern Iraq, security forces are still in the planning stages for an assault. "There are places that should be liberated before Mosul," says Ameri, an influential leader in the PMF. "Before Mosul, we have the area from the north of Ramadi to Al-Qaim near the Syrian border."

Mosul, Iraq's third biggest city and one of the capitals of the self-declared ISIS caliphate, is divided among mostly Sunni Arabs, Kurds and other ethnic and religious minorities. The role to be played by the potentially inflammatory PMF, as well as the Kurdish peshmerga, is still being negotiated.

"Mosul will be a very hard fight, and it will have to be very, very carefully choreographed" to use the right type of forces, says a senior Western official. In a U.S.-brokered thaw in otherwise chilly relations, the Iraqi government and Kurdish leaders have recently agreed to stage Iraqi troops at a Kurdish military base in Makhmour, about 70 miles southeast of Mosul, in preparation for an assault on the city.

"I think, as a fighting force, give them a few months to re-equip and to rest and move on up the Euphrates River and across to Mosul," says a senior Western diplomat. "I think they are capable of doing it, but…it will be a stretch to ask them to do it in the next six months, and then you're into summer. These guys have been fighting solid for two years, and you just can't keep going."

Correction: This story originally spelled the name of an Iraqi colonel incorrectly. His name is Arkan, not Akram.