Bill Weld was a big name in American politics in the 1990s. With his red hair, ruddy complexion and 6-foot-4 frame, he stood out from the crowd of mostly blow-dried politicians. A celebrated prosecutor in Boston and then a top official in the Justice Department under Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, the Republican was elected governor of very Democratic Massachusetts in 1990, and re-elected in 1994 with 71 percent of the vote. Fun and approachable, he once took a fully clothed dive into the Charles River to show how clean it had become. He wanted to run for president, but his socially liberal positions on abortion and gay rights made him an outlier in the GOP. "I looked at it hard in '96," Weld told Newsweek. But after analyzing which moderate states he might have won in the primaries, he realized, "I was still way short."

Twenty years later, Weld, now 71, is back as the vice presidential nominee of the Libertarian Party, having been selected to run with former New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson by members who gathered in Orlando for their convention in May. The party, which usually is seen as a cranky afterthought in presidential races, took a big step toward making a difference in American politics this time by picking two former two-term Republican governors of blue states. The Johnson-Weld ticket is polling around 10 percent—well above the typical 1 percent the party managed to scrape up since its founding in 1971, but was shy of qualifying for the first presidential debate, which required at least 15 percent support in a number of polls. (Making that debate stage is seen as an essential springboard for independent candidates—such as Ross Perot, who won 19 percent of the vote in the 1992 election.) Still, Johnson and Weld have a shot at helping to determine who next sits in the Oval Office, if only as spoilers. So far, despite their Republican backgrounds, the Libertarian candidates have drawn more from Democrat Hillary Clinton than from Republican Donald Trump. But looking beyond this year, a larger question looms for libertarians: How far can a movement vowing to radically reduce government get in a country founded on individual freedom but with a citizenry that loves its student loans, Medicare and other government largesse?

Like any political movement, the Libertarian Party has its wings and rivalries. There are those who venerate the late Ayn Rand, the mid-20th century novelist and philosopher who extolled individual virtue and excoriated "moochers"—anyone who wanted government help—in thick best-selling novels including Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead. It's a sign of how passionate some libertarians can get that Matt Welch, the editor-at-large of Reason, a magazine promoting "Free Markets and Free Minds," faced a Facebook group demanding he read Atlas Shrugged. He didn't. (Weld hasn't read her books either.) Others join the party because of its defense of Second Amendment rights to keep and bear arms or its support of decriminalizing drugs. It's a tent that also holds homeschoolers, who don't want government dictating education; raw milkers, who oppose mandatory pasteurization; and people outraged by the National Security Agency's massive data collection and by the Patriot Act, which makes it easier for Uncle Sam to spy on Americans.

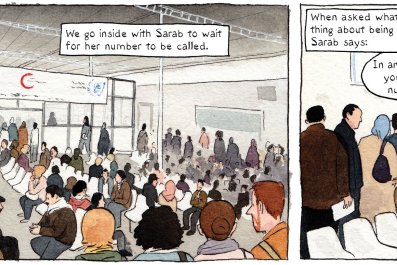

The party is also split between pragmatists and hard-liners. Johnson and Weld are in the former camp, and they took a beating at the Libertarian Party convention. Some members were outraged by their support of the Civil Rights Act (an unwarranted intrusion, some claim, on a merchant's rights to decide who they'll hire and serve), and some even whined about their support for driver's licenses, which they see as Big Brother dictating who can get behind the wheel. One would-be party nominee went so far as to strip naked in front of the convention to demonstrate his commitment to freedom. For the most part, though, Johnson and Weld bucked what might be thought of as the privatize-the-sidewalks crowd, supporting not only civil rights laws but even what many Libertarians see as heresy: some limited forms of gun control.

As a messenger for the libertarian cause, Johnson has strengths and weaknesses, the former being that, like Weld, he doesn't seem like a typical politician. At 63, he is still a tremendous athlete, having climbed the highest peaks on every continent, including Mount Everest. He'd be the first president with a girlfriend instead of a wife. (He gave her Rand's Atlas Shrugged on their first date.) He not only pushes marijuana legalization, he's a toker, although he says he's abstaining during the election—and would also refrain from smoking pot if he gets into the White House. But he can seem like a stoner. He didn't know Aleppo is the besieged city in Syria and recently chirped that people shouldn't worry about global warming since we're all gonna die when the sun explodes—something scientists don't expect to happen for 5 billion years.

Many say the ticket might have more support, including among anti-Trump Republicans, if it had been reversed. "If Bill Weld were at the top of the ticket, it would be very easy for me to vote for Bill Weld for president," Mitt Romney, a fellow former Massachusetts governor, said this spring.

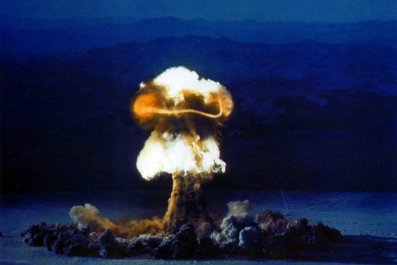

Assuming Weld and Johnson have a strong showing in the November 8 election, can the Libertarian Party keep growing? The question is as old as the republic and its 240-year struggle between small and big government. The essential fight between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton (that guy from the musical) was over the reach of government, with the former advocating for less central power and Hamilton contending that a great nation needs a strong government. It's an argument that also played out through Andrew Jackson's opposition to a central bank in the 19th century; during Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal in the 20th; and as the Homeland Security state was being put into place in the 21st. The problem for libertarians, whether it's the Johnson-Weld ticket or the no-driver's-license crowd, is that government gets bigger every year, even under Reagan or a Republican Congress. Cutting it down would be a Sisyphean task for a Johnson-Weld administration. As Hamilton says to Jefferson in the musical that celebrates the first advocate of Big Government: "Thomas. That was a real nice declaration. Welcome to the present, we're running a real nation."