One of the many laugh-out-loud moments in Martin Amis's new collection of essays, The Rub of Time, is this sentence: "If for some reason you were confined to a single adjective to describe Las Vegas, then you would have to settle for the following: un-Islamic."

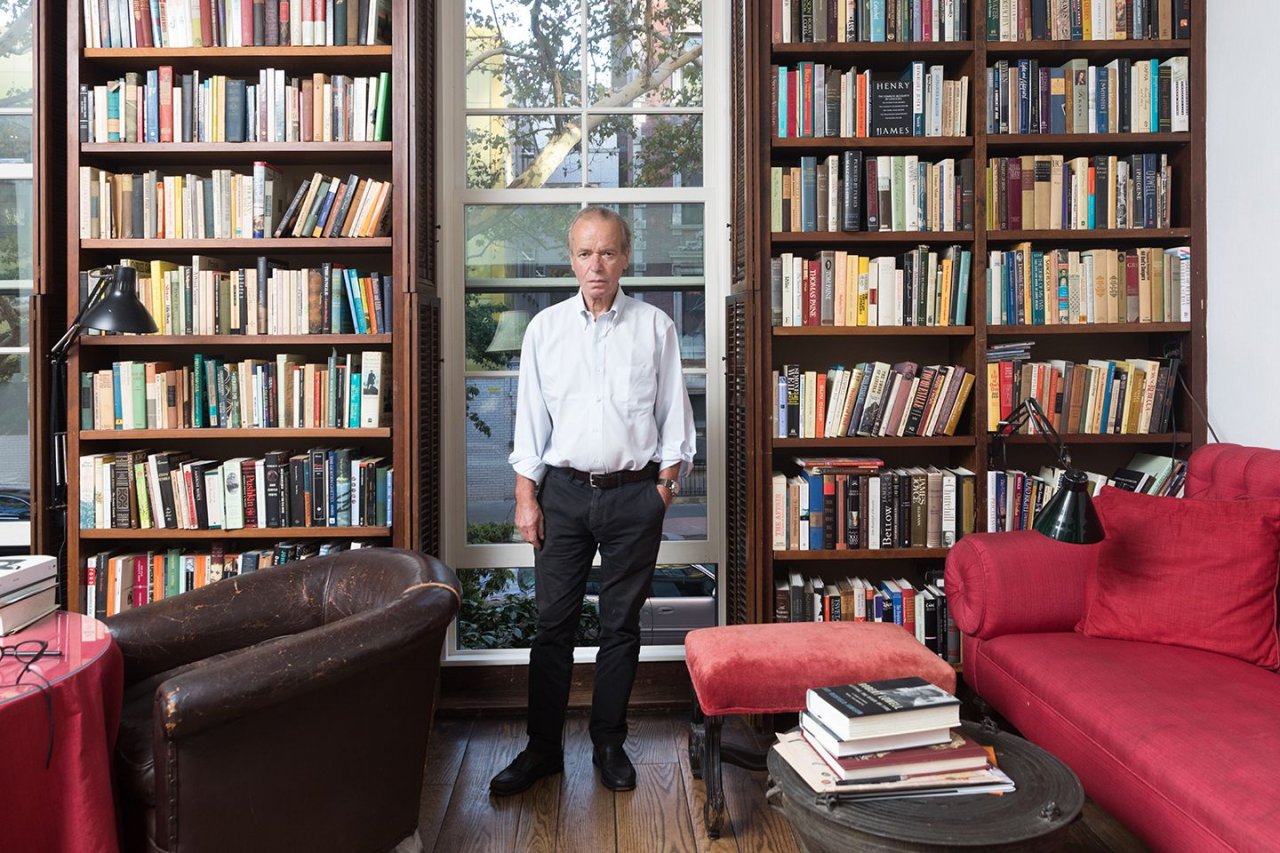

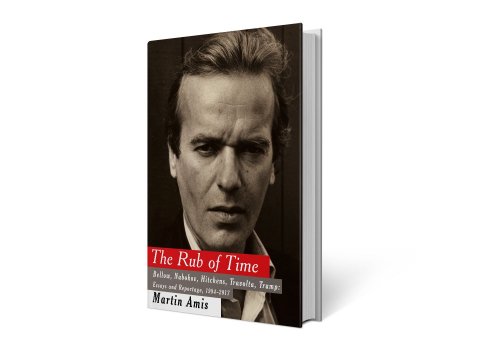

Thus opens "Losing Las Vegas," a 2006 article Amis wrote for The Sunday Times about competing in the World Series of Poker. It is one of 45 pieces (essays, reportage, personal reflections, political commentary) commissioned by a variety of publications over 23 years—1994 to 2017—with topics ranging wildly: pre- and post-presidency Donald Trump, suicide bombers, the now-forgotten resurgence of John Travolta, the death of Princess Diana and gonzo porn, among others. The Booker Prize–winning author is best known in America for his novels—14 to date. The common denominator in all of his work: scathing wit, a piercing eye for detail and prose as elegant as it is fierce. A right hook with a velvet glove.

Most of Rub's pieces are about America, where the British writer has lived since 2011. Amis sees his outsider status as both an advantage and a disadvantage. "There are things you're bound to misconstrue," he said during a wide-ranging interview with Newsweek. "But I'm sure there has to be a freshness to the eye if it's strange to you."

In a piece for Harper's in August 2016, you wrote about the Trump campaign, and though at the time you didn't think he would win, you did joke that "after a couple of days of pomp and circumstance in the White House, Trump's brain would be nothing more than a bog of testosterone." Guess it's not always good to be right. One year into his presidency, is there anything about Trump that surprises you?

No, though his playing of the race card—or the white supremacy card—continues to disgust me. He used to be popular among minorities during his Apprentice days, because he was aspirational and seemed to be encouraging diverse talent. When he quite coldly realized that rational people were never going to get him into the White House, but that frustrated white people might? That he continues to use this great wound in the American psyche as a power play is outrageous.

I describe him in one essay as a spotless, empty vessel. He stands for nothing—well, nothing but money. His son Eric recently said, in defense of his father, that Trump is color-blind—"the only color he sees is green." That was said as unalloyed praise! If one of my sons said that of me, I'd never speak to him again.

You use what you call the Barry Manilow Law to explain his followers: "Everyone who you know thinks Barry Manilow is terrible, but everyone you don't know thinks he's great."

I got that from [critic] Clive James. It explains so much about everything—the alien preference that you'll never understand.

I agreed with your assessment of Trump as "a gawker, a groper, a gloater but not a lecher." And then Stormy Daniels. She claims to have had intercourse with him.

I'm a bit distressed by that news. How could a germaphobe have even a one night stand with a porn star? She must have done something for him—130,000 bucks of something—but I would bet everything that he never actually stuck it in.

Some suggest that we should thank Trump for exposing America's latent racism and misogyny.

Beneath the surface is where all that belongs. You're never going to purify anyone's soul, but you can teach them to behave better, and that's what political correctness—in its often heavy-handed way—has done successfully. We should be grateful to it for that. The idea of bursting free of the shackles of political correctness, and being a lousy, reeking racist and misogynist? We don't thank anyone for that.

On the other hand, some argue that the #MeToo and Times Up campaigns are a delayed reaction to Trump winning the presidency.

When the Harvey Weinstein allegations began, I had a pow-wow with my wife [novelist Isabel Fonseca], and I said, The question is, Why is it so fierce now, when you think that [Roman] Polanski drugged a 13-year- old—sodomized a 13-year-old!—and he bounced back from that. And [Bill] Cosby too; people didn't believe his accusers for years. So I would agree that Trump helped with that.

Do you think the Times Up and #MeToo movements will last or flame out?

I don't see how you can go back. And I don't see how you can go back on many politically correct positions. I believe a real gain has been made.

You've said that you believe an artist's work should be separate from his private life. I'm not sure that's possible anymore. Look at what's happened to Kevin Spacey and Cosby and Weinstein, and what is now happening to Woody Allen.

I think it should not go into the artistic past. You have to give the past it's due, its weight, and say this is what we're emerging from.

Three of the essays in the book are devoted to Vladimir Nabokov, one of your "Twin Peaks," or literary gods—the other being Saul Bellow. A woman recently tried to pressure New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art to remove a Balthus painting because it celebrated pedophilia—the museum refused, largely for the reason you mention above. But I could imagine, in today's climate, someone organizing a campaign to ban Lolita from libraries.

The problem with Nabokov is not Lolita or The Enchanter or Transparent Things; it's the three lighter pieces that he wrote later in his career. Certainly in The Enchanter and Lolita [his attraction for young girls] is taken very heavily indeed. He is not endorsing it, but he seems to in the lighter pieces.

You've been accused of misogyny, largely because of the female characters in your novels. I don't agree, though it was disconcerting to see 15 pieces about male writers—Bellow, Nabokov, the poet Philip Larkin, John Updike. J.G. Ballard, Philip Roth—and just two about women, Iris Murdoch and Jane Austen. Dude! Are there any other female authors you admire?

[Laughs.] I've become a huge fan of my stepmother, Elizabeth Jane Howard. Her five-novel sequence, The Cazalet Chronicles, is genius. I'm also very fond of Lorrie Moore, Alice Munro and Muriel Spark. I'm not at all like Nabokov, who said he was exclusively homosexual in his literary taste. And in his taste in translators too.

One of the most moving essays is devoted to your great friend, the journalist Christopher Hitchens, who died in 2011. You two had a public dispute over Josef Stalin, and a reader once asked if you had made up. You wrote, "We never needed to make up. We had an adult exchangeof ideas." An adult exchange of ideas! That seems an impossibility in America right now. Do you see the extreme divisiveness in this country anywhere else?

It's certainly true of Brexit in England, up to a point. But I think America is the cutting edge of this kind of polarization, where people just don't hear each other. It's really worrying and extreme. It started in 2008, with the Tea Party, which formed in the days following Obama's inauguration. It was [Kentucky Senator] Mitch McConnell who said, "Our intention is to make this a one-term presidency," with this shudder of disgust. It didn't begin with Trump; it began then.

When you wrote about the death of Princess Diana in 1997, you described her appeal as"collateral celebrity." As you wrote, "Equipped with no talent, Diana evolved into the most celebrated woman alive." By 2001, we had Paris Hilton, which led to the Kardashians, and cut to 2017: With a big hand from social media, celebrity is now largely collateral.

Actually, you could see it coming 50 years ago. It was certainly an ele-ment of the sexual revolution in the '70s. But the suspicion that surfaces were going to play a more central role, in quite this heady, creepy way? That I don't really understand, and I haven't read anyone who does.

Have you been paying attention to the Meghan Markle–Prince Harry wedding plans?

No, but I greatly approve it.

Why?

Just because of the diversity question [Markle's mother is African-American]. But I also love the way she looks at him, and the way he looks at her. When I see them, I think, Ah, young love, fairy tale.

I didn't realize you were such a romantic.

Hitchens never gave me a moment's peace about this, but I think the monarch does have a strange function in England—I call it a benevolent irrationality. That's such a rare thing. Usually, the irrational is just violent and terrifying. But in England, there are a few days every couple of years when people feel wonderfully happy and proud, and then they are all right again the next day.

So you see the monarchy going on?

Yes, though there's a great violence done to the children of the monarchy, and particularly in this age of 24-hour micro-inspection. It's a sort of child abuse.

You've been a fan of America for some time. You and your family have been based here for six years. Do you feel at home here?

There are things that bother me more now that I live in America.

Such as?

Race. When I go back to England, it's the first thing I think when I disembark, that you can feel the absence of that whole dimension. It depends, as always, on the socioeconomic surroundings, but many parts of London do feel post-racial. And the health care system here is absolutely moronic, if essentially American—that your health should depend on how much you earn! It's letting money into all sorts of areas where it shouldn't be. America has always been a plutocratic society, but it's a materialist one to a shocking degree.

Let's end on a positive note. What, in your opinion, is hopeful about America right now?

The post-Weinstein reaction feels like a little revolution in consciousness. If you're a gradualist and an anti-revolutionary, like me, that's what you hope for, progress inching forward, with revolutions in consciousness. That was always the big difference between me and Hitch; he loved revolution—America's was why he loved this country so much.

I see that as a big difference between people—whether you're a gradualist or someone who wants to start again. I don't want to start again. Revolutions are very destructive. There haven't been many that worked out well.

"The Rub of Time, Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump: Essays and Reportage, 1994-2017," by Martin Amis (Knopf, $28.95) will be available February 9, 2018.