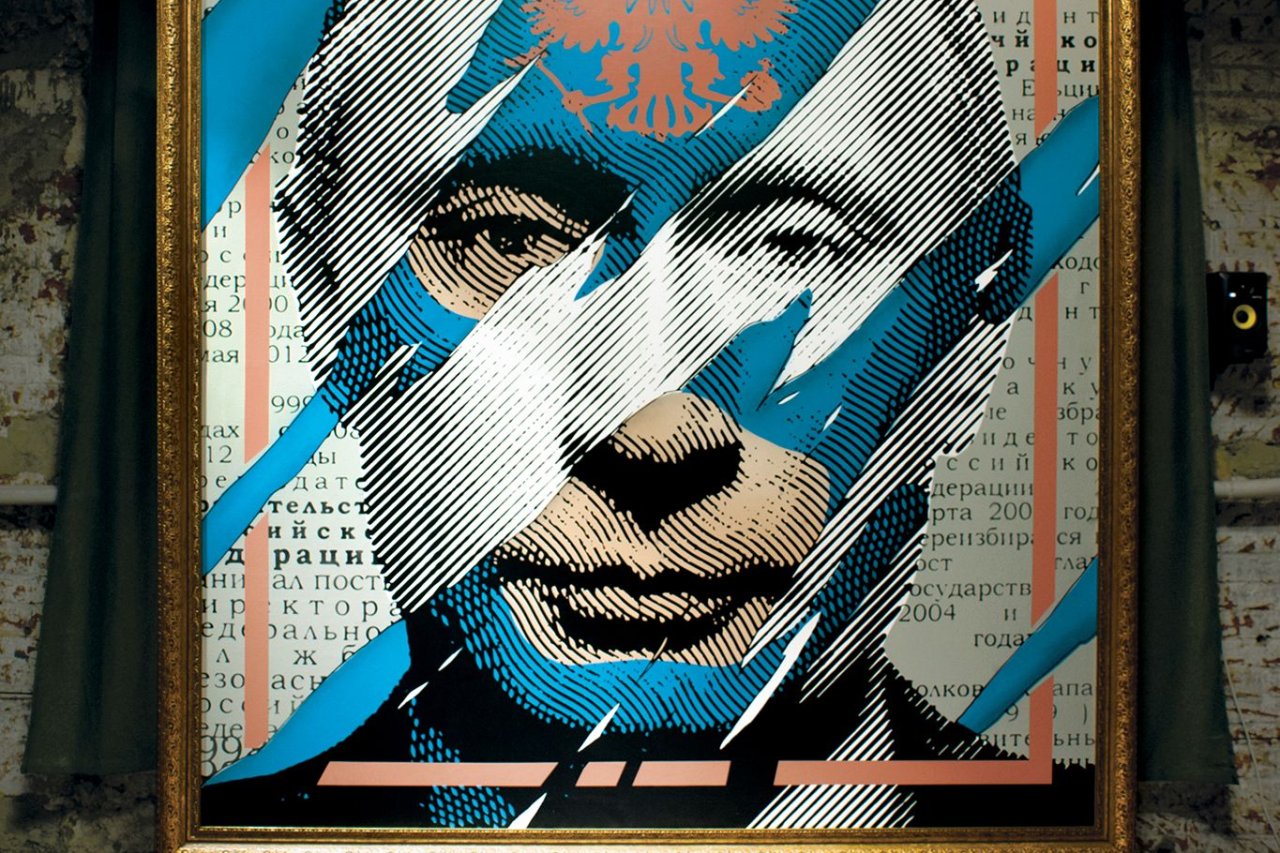

On a cold night in Moscow, in a downtown art gallery, Vladimir Putin is dressed in a red cape, shooting bullets from a gigantic weapon called the "Putin Blaster." His target? Unclear. But there's no mistaking his steely gaze, his grim determination. He is here to save us all.

The Russian president isn't physically at the gallery. He's the subject of it. Putin the caped crusader is one of 30 eye-catching portraits and sculptures at an exhibition in the Russian capital, all of which portray the former KGB man in heroic, iconic and some might say bizarre poses. There's Putin winning an ice hockey championship and Putin cuddling a leopard. There's Putin clad in medieval armor, a Russian flag in his hand, while riding a bear. There's even Putin holding a portrait of Putin, holding a portrait of Putin, holding a portrait of Putin—and so on—like a Russian nesting doll.

The name of the exhibition? "Super Putin." Its curator is Yulia Dyuzheva, 22, a model, activist and journalism student at Moscow State University. "Super Putin" opened on December 6, the day the Russian president officially announced he was running for re-election in March. It's a contest he's certain to win, thereby extending his time in power for another six years. Only Josef Stalin, the Soviet dictator, ruled Russia for longer. "Vladimir Putin is a strong leader who has demonstrated great results," says Dyuzheva. "We should be grateful to him."

Many Russians are grateful. For some people, especially the wealthier residents of Moscow and St. Petersburg, the country's two biggest cities, life has never been better. Russia has the fastest-growing number of millionaires in the world, and Moscow is home to 73 billionaires, according to Forbes. Russian life expectancy is now 71, a record high and an increase of six years since 2000, when Putin was first elected. Putin has also boosted spending on the military, restoring something of the Soviet Union's global influence—a source of pride for millions of people here.

For a significant number of Russians, however, life is still grim. Some 20 million people—about 14 percent of the population—earn just $170 a month. Real incomes have fallen for a fourth year in a row, while some 3,000 primary and secondary schools have no indoor restrooms, including in deepest Siberia. Wealth inequality is among the highest in the world, while corruption involving government contracts alone costs the country $35 billion every year, according to the Moscow-based Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy. In 2010, Dmitry Medvedev, the current prime minister, said the figure was $33 billion—3 percent of Russia's annual gross domestic product.

Meanwhile, critics say Putin has ruthlessly cracked down on dissent and created a sophisticated system of state propaganda to discredit potential rivals. At the same time, those in Putin's inner circle—many of them unelected—have seen their wealth and power increase dramatically.

Dyuzheva, however, is unconcerned. Young people in Russia, she says, see Putin as a modern-day superhero. "There is no one else but Putin with the capability to rule Russia right now," she insists. Her admiration for him is shared by the majority of Russians, according to surveys published by both state-run and independent pollsters. Over 80 percent of Russians say they approve of Putin's performance as president, a rating that has remained constant since the Kremlin annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014—a step that the vast majority here support.

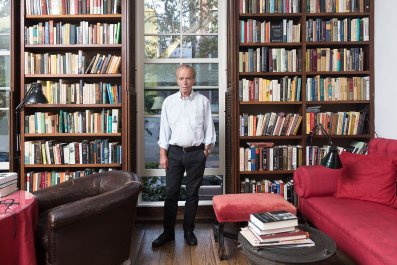

Paradoxically, however, many Russians—about 50 percent—say the country is moving in the wrong direction, a figure that has held steady in recent years, according to the Levada Center, an independent, Moscow-based pollster. What explains this cognitive dissonance? While Putin is technically the head of state, analysts say, many Russians don't associate him with the nation's failures. "Putin is responsible for all the things that are good and often intangible," says Maxim Trudolyubov, a Russian journalist who edits The Russia File, a blog by the Kennan Institute, a Washington-based think tank. "When people are asked about their country and its development, it is the government, the governor, the mayor, salaries, incomes, etc., that people are thinking about."

It's a phenomenon perhaps best illustrated by the numerous online video appeals by ordinary Russians who want the president to solve their problems. The plaintiffs chant or hold up signs reading "Putin—pomogi!" ("Putin—help!"). Notably, they address him as "ty"—the informal version of the Russian word for "you," also used when appealing to God or, in previous centuries, the czar. The most recent video was posted by teachers in the Kurgan region, some 1,000 miles from Moscow, who pleaded with Putin to intervene in a row over unpaid salaries. "This was a desperate act," says Vladimir Kocheulov, the teacher behind January's video. "Teachers in banana republics probably get paid better than we do." Yet Kocheulov was reluctant to blame Putin for his woes. "People in Russia have always relied on their kind batushka to solve their problems," he added, using a Russian word that means either "father" or "priest."

Putin's annual televised call-in has reinforced this image of the president as a dominant parental figure quickly able to resolve Russians' problems. Billed as a "conversation with the people," it frequently features Putin admonishing officials on air and instructing them to carry out housing repairs or build gas pipelines to remote areas. Once, he gave a dress to a little girl from a poor family and invited her to a New Year's party at the Kremlin. "[It's] Putin magic," says Trudolyubov. "In the popular imagination, [he] is responsible for everything."

For some Russians, the president isn't merely responsible for everything; he is everything. As Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of the Russian parliament, put it in 2014: "There is no Russia today if there is no Putin." Unlike in Western countries, where politicians are seen mostly as ordinary people, for millions of Russians, Putin is the living, breathing embodiment of the country. Which is why criticism of the "national leader" is frequently interpreted as criticism of Mother Russia. "I don't particularly like Putin or his United Russia party," a Russian celebrity once told me, on condition of strict anonymity because she supports the authorities in public. "But I would never dream of criticizing either of them because I am a patriot."

Attitudes such as these have led to heated conversations in homes across Russia. "You are a traitor to your country!" Olga, a 75-year-old woman in Voronezh, a city in central Russia, shouts at Svetlana, her 40-year-old daughter, after she criticized Putin. (Both women asked that their names be changed for this article because they didn't want publicity.) "I feel offended for Russia when you say bad things about Putin," explains Olga, who receives a monthly government pension of just 8,000 rubles ($142) and relies on financial help from her daughter to get by.

This devotion to Putin is reflected in popular culture. During Putin's first term, a female pop duo called Singing Together scored a hit with an infectious song. Part of its chorus: "I want a man like Putin, full of strength." Later, in 2015, Timati, one of Russia's biggest rap stars, released a track called "My Friend Is Vladimir Putin," which contained the lines, "The whole country is down with him/He's cool, a superhero." Now, as Russia gears up for the March presidential elections, a singer named Vyacheslav Antonov is stirring patriotic hearts with a rousing rock tune vowing to follow Putin into the "final battle" against NATO.

It's not just songs. There are murals, portraits, even statues of Putin, including a bronze bust near St. Petersburg that portrays the Russian president as a Roman emperor. All are manifestations of what critics say is a cult of personality around the longtime Russian leader that began to accelerate rapidly during the standoff with the West over Crimea.

But there are distinct differences from the more traditional personality cults that once existed in the Soviet Union and China, as well as in North Korea today. Putin is not remaking the country in his own image, says Sam Greene, director of the Russia Institute at King's College London. Instead, his personality cult is a symptom of the lack of institutions that could rival him for authority. "The parliament, the courts, the constitution, even the church," he says, "have been sapped of power in the service of a single arbiter, a single guarantor and a single symbol."

Furthermore, Putin's personality cult isn't driven by mass political repression, unlike the case under Stalin. Instead of gulags and summary executions, the Kremlin relies mainly on shadowy advisers who have carefully shaped and maintained his image. "This myth that Putin decides everything, that there is no alternative to Putin, we worked on constantly throughout his first two terms," says Gleb Pavlovsky, a former key Kremlin adviser. "Just as everyone knew the Soviet Union was Lenin's state, for the majority of Russians today, Russia is Putin's state."

Putin's popularity, Pavlovsky says, is largely founded on memories of the 1990s, when, under President Boris Yeltsin, salaries and pensions went unpaid for months. Those hardships followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, a period of colossal deprivation for millions of Russians.

The former KGB man's early years in office, however, coincided with a massive increase in the global price of oil, Russia's main export, and living standards rose dramatically. "You are dealing with a nation of survivors," Pavlovsky says. "People remember when they were barely able to feed themselves and their families. Although there is monstrous wealth inequality, people view what they have now as good fortune, rather than something that should be taken for granted."

Pavlovsky, a 66-year-old former Soviet dissident, worked for the Kremlin under both Yeltsin and Putin. One of the architects of Russia's "managed democracy," he was dismissed in 2011 for opposing Putin's third presidential term. "We enacted a whole story about a spy who had ensconced himself among the authorities and then suddenly emerged and went over to the side of the people," he recalls. "As if the Kremlin gates had opened up, and out of them came a people's president, one who—unlike Yeltsin and the Soviet leaders before him—spoke the language of the people. It was like a theatrical production, and Putin quickly learnt his role. He was like an actor who learnt and improved on the part given to him."

Although he is critical of Putin, Pavlovsky initially saw the Russian leader's rule as an opportunity to bring stability to a country that was in danger of disintegration during the chaos of the post-Soviet breakup. But the achievement came at a cost. "In the 2000s, during Putin's first term, we consciously stamped down on the political process," Pavlovsky admits. "We carried out the politics of managed democracy: If you had a major conflict, you had to come to us, to the Kremlin, to Putin, and we would help you resolve it. You couldn't appeal to anyone else. This was meant to be a temporary measure—a temporary therapy—people had to have the chance to recover from the horrors of the previous decade. But then it turned out that this was very convenient, not to mention very profitable, for the authorities. This is one of the things I feel responsible for, unfortunately."

Another strategy was to prevent Putin being personally associated with any failure. "That's why we didn't let him go to the scene of the Kursk disaster," Pavlovsky says, referring to deaths of 118 sailors on board a Russian nuclear-powered submarine that sunk in 2000.

Yet for all his Kremlin scheming, Pavlovsky insists the idea that Russians exist in a constant state of Putin worship is a myth. "This is propaganda—very powerful propaganda," he says. "The Russian state is very weak. This is not some kind of powerful government machine. It compensates for this with the methods that we worked out in the 1990s and the 2000s—media propaganda in conjunction with political manipulation."

Despite the chest-thumping of some of Putin's more enthusiastic supporters, it's unclear exactly how deep this devotion runs. The Russian president has never once taken part in a debate with a rival presidential candidate. For all his sky-high approval ratings, the Kremlin is unwilling, opposition figures say, to test Putin's popularity by allowing him to run against independent candidates such as Alexei Navalny, the anti-corruption activist who has been barred from the upcoming presidential elections. Although he is polling at just 2 percent nationwide, Navalny is the only politician able to bring Russians onto the streets, and his online investigations into high-level corruption have millions of views on YouTube. In 2013, the only time he has been allowed to stand for public office, Navalny took almost 30 percent of the vote at the Moscow mayoral elections, despite being banned from state television. Navalny compares Putin's approval ratings to those of Robert Mugabe, the Zimbabwean dictator who was removed from power in a military coup last year. "Despite his 90 percent approval ratings, where were Mugabe's supporters when he was toppled?" Navalny said recently. "They were nowhere to be seen. This is the usual story with dictators. Ratings are a fairy tale."

Numerous investigations by opposition journalists have revealed that the Kremlin struggles to get Russians to attend—at least voluntarily—rallies in support of the president, and is forced to strong-arm government employees or students to boost turnout. What would attendance be like if the authorities did not force people to go to pro-Putin rallies? That's what opposition activists in Tyumen, an oil town with a population of just over half a million people in western Siberia, decided to find out. On December 31, posing as Kremlin supporters, they staged a rally that was—on paper—in support of a fourth presidential term for Putin. The event was advertised in local media and online and was held in the afternoon, on a non-workday, in the center of the city. The attendance? Just seven people, reported Novaya Gazeta, an opposition-friendly newspaper.

Back at the "Super Putin" exhibition, the passion for Putin on display is also not quite as simple as it seems. Things in Russia rarely are. "For me, this exhibition is an act of coming to terms with the fact that Putin will be president forever," says Alexander Donskoi, a former opposition politician who dreamed up and financed the showing. The former mayor of Arkhangelsk, a city in northern Russia, Donskoi spent nine months behind bars on what he says were trumped-up fraud charges after announcing his plans to run for president in 2008. "Most people in Russia don't… think there is anything wrong with one person being in power for life, like the czar. They have an infantile belief in the authorities," Donskoi says. "The 'Super Putin' exhibition is a reflection of that. I asked around and found a person who really, genuinely loves Putin, and asked her to act as the organizer and censor for the exhibition."

That's one, albeit unusual, way of dealing with Putin's protracted period in power. Others take a more pragmatic approach. In January, when Putin's election campaign office opened in central Moscow, dozens waited in line next to a sign reading, "A strong president. A strong Russia." Many were waiting to plead for assistance with housing and other problems. "I'm hoping that Putin can help me," said an elderly man who gave his name only as Oleg. "But even if he doesn't, I'll vote for him all the same—I'm a patriot."

Natalia Shevtsova was also in line. She's a middle-aged woman—one of thousands who invested their life savings in apartments at a construction project in southern Moscow in 2006. The apartments are still unbuilt. Shevtsova says government officials have been unable—or unwilling—to help her get her money back. Her only hope now, she says, is Russia's longtime leader.

"I don't support Putin," Shevtsova says. "But who else am I going to turn to for help? This is a dictatorship. I have no other choice."