"Women, you have to treat 'em like shit." —Donald Trump, New York magazine, November 9, 1992

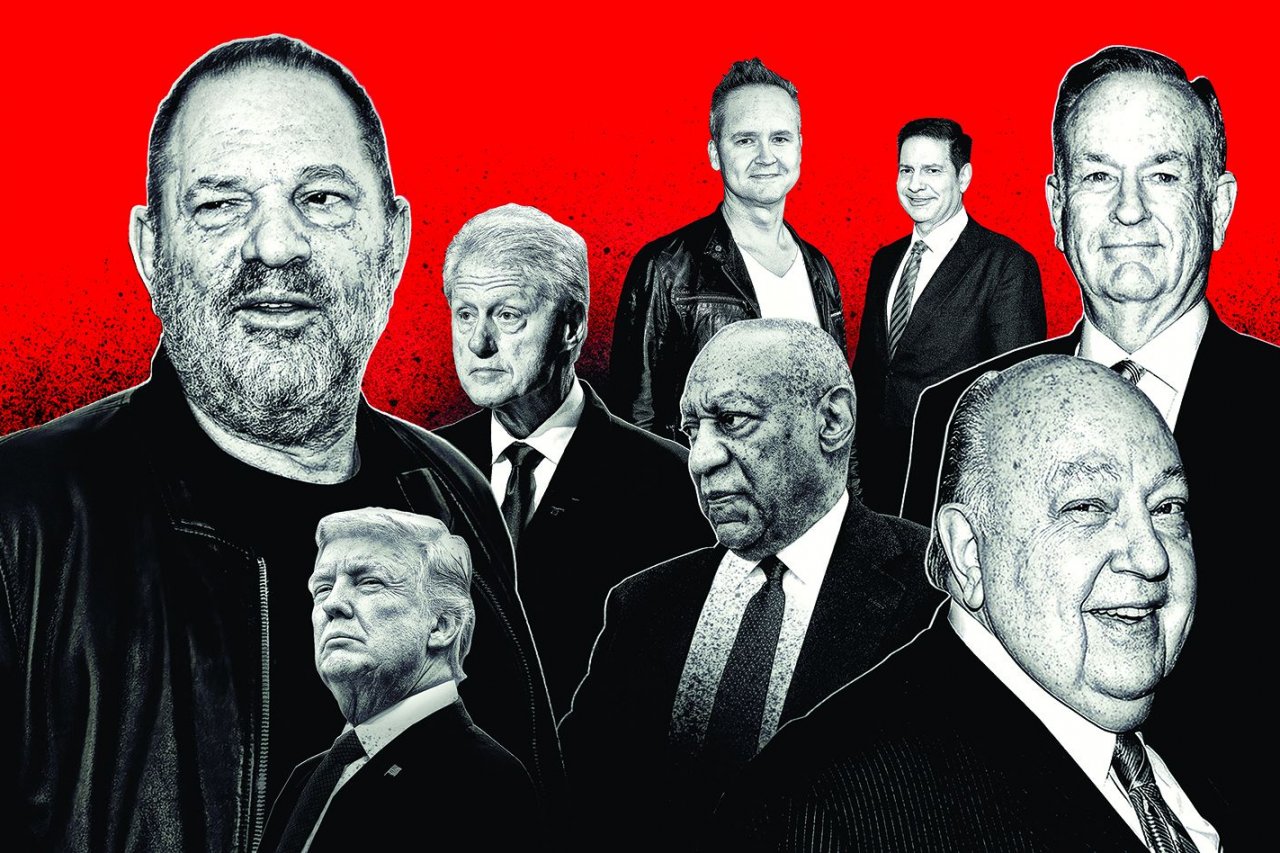

After centuries of indifference to or even tacit (and sometimes open) sanctioning of sexual harassment, abuse or assault, we are suddenly in the midst of a cock conflagration. Powerful men in Hollywood, politics, journalism and many other fields are being pilloried, sacked or jailed for piggish or even criminal behavior toward women.

To understand how this bonfire started, we must speak frankly about the Garden of Dicks, a mythical place in the caveman lobe of the male brain. Like that other primeval paradise, the Garden of Eden, men have tried for millennia to create it here on Earth.

The Garden of Dicks is a Hooters. It's an NFL locker room. It's the Vatican. It's the Rolling Stones' private jet. It's Harvey Weinstein's suite at the Tribeca Grand Hotel.

It's a top modeling agency in New York City run by a man who, after years of preying on his models, was disgraced for having sex with underage girls. He excused himself by saying, "I'm a man, and I have urges."

It's a corner office at Fox News decorated with the memorabilia of great power—including a brick from Osama bin Laden's compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan—inhabited by a muttony executive who relentlessly propositioned female colleagues, grabbed kisses, demanded sexual favors for jobs and said things like, "You know, if you want to play with the big boys, you have to lay with the big boys." And, "Well, you might have to give a blow job every once in a while." Down the hall, that executive's pasty star was allegedly sending gay porn, jerking off on late-night calls to female underlings and making numerous other unwelcome sexual advances.

It's an online "review board" where an estimated 18,000 men, many of them reportedly white-collar tech workers, ranked the sexual skills of trafficked Korean women.

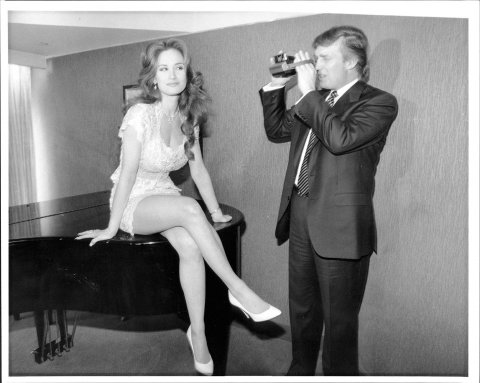

It's a beauty pageant afterparty, where a 1997 Miss USA contestant met the pageant's owner. "He kissed me directly on the lips," Temple Taggart told The New York Times about her encounter with the man who is now president of the United States. "I thought: Oh my God. Gross. He was married to Marla Maples at the time. I think there were a few other girls that he kissed on the mouth. I was like, Wow, that's inappropriate."

In the Garden of Dicks, the sense of entitlement regarding female bodies is so massive that many men assume women will "let you do anything," as Donald Trump has suggested on more than one occasion. "They'll walk up, and they'll flip their top, and they'll flip their panties," he once told radio host Howard Stern.

In the Garden of Dicks, a man can say something like that and believe it, because there's always a Stern or a Billy Bush to snicker and egg him on. "I moved on her like a bitch, but I couldn't get there. And she was married," Trump said to a fawning Bush on a hot mic en route to filming an Access Hollywood segment over 10 years ago. "And when you're a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything."

Then there was the Republican presidential debate in March 2016—four men on a stage—when Trump boasted on live, prime-time TV about the size of his penis.

In the Garden of Dicks, it's always about the dick.

In the Garden of Dicks, plausible deniability is taken for granted. When 17 women came forward during Trump's campaign last year to allege he had done that pussy-grabbing, forced-kissing, tongue-down-the-throat thing to them, he called them all liars. "The events never happened. Never. All of these liars will be sued after the election is over," he said during a speech in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, weeks before he was elected. His fans roared like beasts.

Trump still hasn't sued those "liars." Perhaps because he was so busy moving into the Oval Office, where he immediately set up a Rose Garden of Dicks. His former chief adviser, Steve Bannon, called House Speaker Paul Ryan "a limp-dick motherfucker," and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell "a spineless cocksucker." Unofficial adviser Roger Stone lost his Twitter account for calling Trump critics "cocksucker" one too many times. And Trump installed a communications director who exited shortly after calling a New Yorker reporter and saying, "I'm not Steve Bannon. I'm not trying to suck my own cock."

In the Garden of Dicks, women come and go, working, serving and servicing—trying to earn a living wage, searching for a husband or a job, looking for venture capital or just a good time, seeking an advanced degree or a part in a movie. Often, we have no choice. We enter a room and instantly know: Oh, it's that place. There's always something unnerving in the air, like the men there have just laughed at a joke we aren't supposed to hear.

And, eyes averted, we carry on.

Coming to a Head

Trump's victory in November was an insult to all the women who had accused him of sexual assault or harassment and been called liars. It was also a nightmare made flesh for the millions of women who heard echoes in Trump's degrading remarks about women of the harassment or assaults they've endured. Many called his triumph a repudiation of feminism. And yet, a year after his ascension, his pungent brand of misogyny is besieged. For the first time in history, powerful men in a multitude of fields are being smacked off their perches because of their rapacity, while women all over the world are finally speaking out.

This uprising has been a long time coming. Forty years ago, legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon wrote a seminal paper for a law school class called "Sexual Harassment of Working Women." In it, she argued that sexual harassment violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the federal law that prohibits employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of sex, race, color, national origin and religion.

In 1986, the Supreme Court ruled that sexual harassment can be an actionable form of sex discrimination and that harassment can include creating a hostile work environment through rape and other unwelcome sexual aggressions. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) defined sexual harassment as "unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature."

After that ruling, women filed more and more cases claiming they'd been harassed in the workplace. Corporations responded by offering diversity training, and a whole new legal subculture developed to sue and to defend the accused. Along with that came forced arbitration, which dramatically lowered the number of cases that went to trial. Good for men, bad for women.

Thirty years after the Supreme Court's ruling, sexual harassment remains rampant and under-reported. The vast majority of incidents—75 percent—are never reported because of fear of retaliation, a fear that, according to surveys and the responses to women who have accused public figures like Trump, Weinstein and Hollywood director Brett Ratner, is well founded.

During the decades when sexual harassment law was being framed in the courts, Trump was crafting his persona as a preening predator. He demeaned women in public forums and bragged about sexual assaults. (For some, that is part of his appeal.) He also backed fellow harassers. He hired the disgraced and deposed former Fox executive Roger Ailes as a campaign adviser. "Some of the women that are complaining, I know how much he helped them," Trump said on NBC, as sexual assault allegations against Ailes started piling up in July 2016. While massively popular Fox host Bill O'Reilly was being pushed off the air amid revelations that the company had paid tens of millions to settle sexual harassment claims against him, Trump told The New York Times, "I don't think Bill did anything wrong."

There is one sexual predator Trump has not stood up for, though: The man whose attacks on female celebrities and young underlings were so numerous and so familiar in style and substance that he spawned an online revolt, hashtagged #MeToo. Harvey. And just like that, Weinstein and the million-strong #MeToo movement baked up the perfect cake to serve on the anniversary of the election of the nation's first Pussy Grabber in Chief.

'Don't You Know Who I Am?'

The women come and go, talking of sexual harassment.

Is it fair to focus on Trump during this #MeToo spring, when our Twitter feeds and news feeds and coffee breaks are teeming with vile misdeeds by so many other bold-faced names? After all, he's not being investigated by the New York Police Department for rape, as Weinstein is. He's not been forced to resign, as NPR's head of news, Mike Oreskes, was. He hasn't even felt compelled to apologize for his treatment of women, as Alec Baldwin, Dustin Hoffman and former President George H.W. Bush have. But it is fair to put him in the witness box, because he is the president, and because he is revered by millions of men and women, and because he is unrepentant.

Seventeen women have accused Trump of sexual misconduct, claiming he touched them sexually without their consent—actions that fit the legal definition of sexual assault in most states. None of these women knew one another when they came forward, but they described similar acts, revealing a pattern of behavior that spans decades.

To put Trump's history in perspective, while Bill Clinton was seducing a White House intern in 1996, Trump was at a New York City restaurant allegedly having women walk across a table, while looking up their skirts and commenting on their genitalia with model agent John Casablancas (who had brought five or six models along for Trump's inspection). While special prosecutor Ken Starr was investigating Clinton for having sex in the Oval Office with that intern in 1997, Cathy Heller was attending a Mother's Day brunch at Mar-a-Lago when she met Trump. She says he immediately kissed her on the lips and struggled with her when she pulled away. The same year, teen pageant contestants recall him wandering into their dressing rooms. As Clinton's impeachment loomed in 1998, Trump allegedly touched the breast of Karena Virginia while she waited for a car outside the U.S. Open. "Don't you know who I am? Don't you know who I am?" she said he told her after she recoiled.

Beauty pageant contestants have accused Trump of going into their dressing rooms unannounced and uninvited in 1997, 2000 and 2001 while the women were in various stages of undress. Trump has not denied it. On the contrary, he bragged to Stern that he could "get away with things like that." (Stern sniggered that he was "like a doctor.")

Creepy DMs and Casual Debasement

Most men aren't predators, and most women who complain about them aren't man-haters, but too few men have been willing to risk exclusion from the powerful boys' club to call out the pigs. That wall of male omertà now seems to be cracking in a few industries—Hollywood, politics and the news media. After reading actress Annabella Sciorra's account in The New Yorker of an encounter with Weinstein that she says was a rape, director and screenwriter Brian Koppelman (Ocean's 13, Showtime's Billions) tweeted that the story "made me almost physically ill." He added: "I've written before about how complicit all men are in the casual debasement of women at poker tables, on golf courses, and etc."

Not that women are waiting to be rescued by their menfolk. After Weinstein was filleted on all media platforms, anonymous female journalists crowdsourced "Sh**ty Media Men," a now-widely shared list of dozens of working journalists, mostly in New York, Washington and L.A., accused of sexist behavior ranging from "creepy DMs" to "rape." The list led to some women publicly putting names behind accusations. Hamilton Fish, president and publisher of the progressive stalwart The New Republic resigned in early November, and a former editor of The New Republic, Leon Wieseltier, lost funding for a new project after admitting that he'd committed "misdeeds" against female colleagues.

Take My Humiliation, Please

In the Garden of Dicks, there is one peculiar fear: a loss of power; castration by other means.

In his book Trump: The Art of the Comeback, the future president of the United States wrote: "Women have one of the great acts of all time. The smart ones act very feminine and needy, but inside they are real killers. The person who came up with the expression 'the weaker sex' was either very naive or had to be kidding. I have seen women manipulate men with just a twitch of their eye—or perhaps another body part."

And you never know when one of these "killers" has blood coming out of her "wherever."

One of the more astonishing allegations regarding Weinstein is that he masturbated into a potted plant in front of a female TV reporter. When the avalanche of Horny Harvey raunch crashed over us in October, his puzzling proclivity for whipping out his genitals in mixed company seemed like a sui generis vice. Then, thanks to the #MeToo campaign, female journalists publicly accused Mark Halperin, a top political journalist, of sexual assault and harassment, including the claim that he once masturbated in front of a young woman at work. According to dozens of accounts from female Fox employees, Ailes also liked to drop trou when a pretty young thing happened into his office suite.

Powerful men exposing themselves to subordinate females doesn't shock James Gilligan, a psychiatrist and author who has spent decades working with rapists and has written books on male violence, including Violence: Reflections on a National Epidemic. Gilligan believes sexual harassment is related to men's shame and humiliation over their perceived lack of sexual or worldly power. "The purpose of this kind of behavior is for a man to try to undo his own feelings of inadequacy by transferring that onto the woman by humiliating her," he says. "One of the ways you can most deeply shame somebody is by attacking their genitals or exposing your genitals to them. There is no more humiliating thing you can do than to sexually overpower somebody, to subject them to unwanted sexual activity."

Gilligan's research with rapists over a 10-year period in a San Francisco prison led him to believe that fear of impotence—in the literal sexual sense and in the figurative sense of worldly power—lurks behind all acts of sexual aggression, from harassment to rape and other kinds of violence. "What underlies this compulsive male sexual aggression is the fear that one is not sufficiently potent," he says. "What I've observed from working with violent offenders is that the will to power is exaggerated in proportion to how impotent the person feels."

Trump, says Gilligan, "is a perfect example" of the type of man who feels humiliated and must cast off that shame onto women. "No one wants to humiliate others unless they feel humiliated. Not only the 'pussy grab,' but the 'small hands' discussion at the [first primary] debate. Here is a man running for president of the United States trying to assure people that his penis is big enough. We've never had a president so obsessed with his own inadequacy."

Alternate Reality Show

Trump's time in office has been filled with an outpouring of outrage from women, first in the form of the Women's March in January and now the #MeToo movement. The frequency of the term "sexual harassment" nearly doubled on Facebook and Twitter in 2016—the year of Trump's candidacy—from 3.8 million mentions the year prior, to 6.6 million—according to social media analytics firm Crimson Hexagon. This year, that number rose again, by a million, according to the same analysis—even while news media mentions of "sexual harassment" dropped in 2017 compared with 2016.

The anger and expiation has spread to Europe. British Prime Minister Theresa May had to replace her party's defense secretary after allegations of sexual harassment, and at least two other prominent U.K. pols are scrambling to save their careers after accusations from women. "The dam has broken on this now, and these male-dominated professions, overwhelmingly male-dominated professions, where the boys' own locker room culture has prevailed, and it's all been a bit of a laugh, has got to stop," declared Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson.

Gretchen Carlson, a journalist who sued Fox and won $20 million over Roger Ailes's harassment when she worked there, believes this revolution is surging. "In the news cycle, we don't keep talking about things, even when we should. But news outlets are hungry to find out more stories from women, and that says to me it's a tipping point."

Some scarred veterans of the gender wars are less optimistic. They know the pattern for the women's movement has too often been one step forward, then two steps backlash. They also know that hashtag campaigns come and go. After Elliot Rodger killed six people and injured 14 others in a California rampage in 2014 that was fueled by misogynistic rage, a #YesAllWomen hashtag campaign drew forth millions of stories of hatred and violence against women, and churned up more social media conversation than #MeToo. The outpouring revealed that the United States was suffering from a public mental health crisis, with millions of women being victimized.

That hashtag burned bright, then flickered out.

Speak, Mammary

For years, it has almost always played out like this: A woman accuses a famous man of harassment, and that famous man calls her a liar. The media reports it, expensive lawyers rush in to also call the woman a liar and maybe a gold digger and maybe worse, and then both parties slink off to mediate the case behind closed doors. The woman—previously unknown, usually—fades from view, sometimes with payoff and a nondisclosure agreement or a court-ordered gag stitching her mouth shut for life.

When women spoke out, they invariably became unwilling contestants on an alternate reality show. An anonymous Weinstein accuser told New Yorker writer Ronan Farrow she didn't want to attach her name to her story because stepping forward "is like choosing a different life path." Powerful men with access to media influencers could always maintain control of the narrative longer (and louder) than their accusers, and those women usually found themselves portrayed as shrews or schemers or psychotics. And so they ate their pain.

Last year, New Yorker Jessica Leeds told The New York Times about an incident on an airplane in the early 1980s, when Trump, seated next to her, groped her during the flight. Trump later crowed from the podium of a campaign rally that she was too ugly for him to have done what she described. On election night, Leeds was invited to a party to celebrate the first female president. "About 10 o'clock, I folded my tent," she recalled. "To pick up the newspaper the next morning was like a punch in the stomach."

But in fall 2017, the harassers and abusers and rapists can no longer assume their prey will scurry back into the forest, doe-eyed and out of sight. Women have wrested the cudgel of public humiliation from the criminals, and the media is no longer the pliant tool of the wolves and pigs it once was. Trump's election was a powerful blow to his accusers, and they were all ghosted by the media. They receded into history, except for Summer Zervos, an Apprentice contestant who said Trump kissed her aggressively and touched her breast during private meetings. She is suing the president of the United States for defamation for calling her a liar.

On the anniversary of the release of the Access Hollywood tape, UltraViolet, a women's group, set up a 10-by-16-foot screen near the White House and showed the video continuously for 12 hours. If President Trump spied it from his terrace, he didn't say anything. And why would he? He has the presidential bully pulpit to label live women "fake news." At a Rose Garden press conference in October, he replied to a question about the accusations: "All I can say is it's totally fake news. It's just fake. It's fake. It's made-up stuff, and it's disgraceful what happens, but that happens in the world of politics."

Journalist and author Natasha Stoynoff is professionally trained to stick to the facts. After Trump's Access Hollywood tape was released, Stoynoff wrote in People magazine about an incident at Mar-a-Lago in 2005, where she had been dispatched to interview Trump and his wife, Melania, on the eve of their first anniversary. Stoynoff wrote that while his pregnant new wife was in another room, Trump led her into a room, then pushed her against a wall and stuck his tongue down her throat, telling her they were going to have an affair. Stoynoff had corroboration: She told friends, family, her colleagues and a journalism professor about it at the time. But she didn't make a public accusation, and the magazine published her story about the Trumps' impending bundle of joy.

During the campaign, Trump denied her accusation with a characteristically degrading flourish, announcing at a rally, "Look at her…. I don't think so."

That galled, but Stoynoff was stunned and soothed by the many people who contacted her to share stories of sexual assault and harassment after she published her article. "So many men had no idea this had happened to so many women—I didn't know either! That's what the #MeToo movement has done. There is power in numbers."

This past year, Stoynoff has been working on an unrelated book and publishing a text and video series for People called "Women Speak Out." She is optimistic in spite of being one of the many women the most powerful man in the world has branded a liar. "Whatever damage this administration does to women today, I'm confident we'll just fix it as soon as this administration is gone. Even if they want to grab us by the hair and drag us to their cave, they are a mere blip in the history and progress of women, and they will never undo the knowledge we've gained or the progress we've made. Never."

Catharine MacKinnon has been fighting this fight for 40 years. She's now 71, still an avid anti-porn feminist, still teaching law at the University of Michigan. Her advice: If women (and men) want real change, they should fight for more codified rights, in the form of an Equal Rights Amendment.

She also says the #MeToo-ers should prepare for a bilious backlash. "Don't assume that the women who have come forward—the real drivers of this awareness—won't be assailed and reviled. Don't assume that because there are so many of them, the awareness they are creating is irreversible. Don't assume that a lot of sympathy won't be generated for the consequences to these men for their voluntary behavior. White male supremacy didn't get where it is today by allowing reality to win."

Update 3/23 6:30 p.m.: We have removed Matt Taibbi from this article. The prior version of this piece included a reference to him and his book eXile. Several reviews from 20 years ago said the book was satire. Grove Publishing marketed the book 20 years ago as non-fiction and in 2017 added clarification saying: "This book combines exaggerated, invented satire and nonfiction reporting." Grove said the book was categorized as such because it contained a mix of fiction and non-fiction.