🎙️ Voice is AI-generated. Inconsistencies may occur.

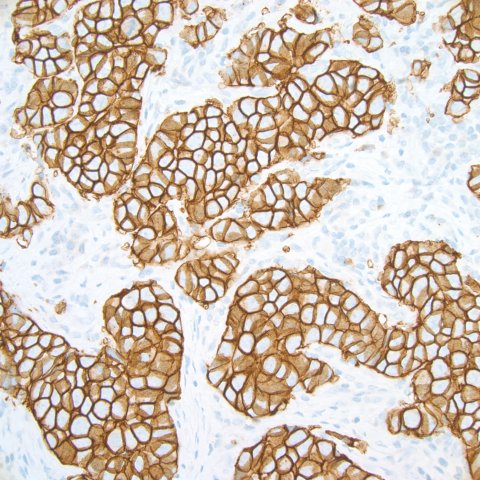

In the window of her office at Stanford University Medical Center, Dr. Kimberly Allison keeps a transparency of breast cancer cells. "Beautiful," she says, gazing at the tumor cells, each traced in a thin orange line and arranged in clusters resembling honeycombs.

Allison's job is to examine tissue samples for clues that can explain what exactly has gone wrong inside a person's cells. She began her career in the mid-2000s, right when medical researchers started to recognize that all tumors and cancers are genetically and biologically distinct. In other words, two women with breast cancer might have two different types of cancer with little in common other than that they both occur in the breast.

Suddenly, drugs that targeted specific types of cancer were hitting the market, and a pathologist's description of cancer became a powerful guide in determining which patients received the new treatments. The first of this class of drugs, Herceptin, made its debut in 2006 to treat women with breast cancer tumors that have abnormally high numbers of a cellular receptor called HER2 that stimulates growth of cancer cells.

Allison became a breast cancer expert, in large part because of the HER2 discovery. "It was exciting to me that you could make such a difference in a patient's treatment plan," she says. "You weren't just describing cancers. You were saving lives."

Then, in March 2008, at the age of 33, she felt a shelf-like formation under her arm and went to the doctor for a diagnosis. She had breast cancer. "It was completely disorienting," she says. She remembers thinking, "I look at this all the time under the microscope, but this isn't my story."

Slow-growing cancers appear almost like normal cells under a microscope's lens. But then, Allison says, there are "big, bad and ugly" aggressive cancers. Instead of being neatly arranged into structures, these cancer cells swell and lose their tidy alignment. That's what Allison saw when she peered through the microscope at her own cells. The cells' outer membranes also glowed orange—the color of a special stain adhering to HER2 receptors. Allison had HER2-positive breast cancer.

It's not often that scientists and physicians are stricken with the precise disease they study, but when it happens the shock is unsettling. Even after years of research, experiencing a familiar illness firsthand can make the disease suddenly terrifying. It can lend new urgency to tedious bench work that probes the molecular and genetic undercarriage of illness—but researchers tossed into the turmoil of life as a patient can also quickly lose sight of the neutrality they've developed.

In 1971, Ernie Garcia, a young astrophysicist turned radiologist at Emory University, developed software to allow cardiologists to peer into patients' hearts. His Emory Cardiac Toolbox includes a program that tracks a "tracer"—radioactive material injected through veins—into the muscle of a beating heart. On a screen, physicians can watch chambers light up in bright colors if blood flow is normal, or turn black if it's not. An abnormal reading indicates coronary heart disease, which can cause heart attacks and affects 15 million Americans.

Garcia spent the next three decades working with heart patients. But he missed the signs completely in 2008, when he had a heart attack. One night in April, after a pasta dinner—heavy on the garlic—he felt a sharp pain in his chest. He attributed it to heartburn. "The esophagus and the heart tend to share a lot of the same nerves," he says with a shrug. When he woke up the next day, his heart was racing. Colleagues at Emory University Hospital hooked him up to the toolbox he had invented to see how blood was flowing through his heart. Afterward, Garcia found his cardiologists just outside the door, huddled around a screen displaying his results. "They didn't even have to say a word," he says. The blackened sections showed that the sharp pangs he felt months earlier were signs of a heart attack caused by coronary heart disease, and the damage was severe. Twenty percent of the functionality in his left ventricle was lost forever.

Garcia's expertise had almost killed him. He dismissed his symptoms because over years of studying fatal heart conditions he had persuaded himself that he would never develop one. That psychological distance allowed him to treat others without fretting over the inevitability of his heart's decline. "It gets to the point where you have to put a wall up—thinking, I'm not getting that," he says. "Then, years later, that wall gets you when you think the symptoms are not real."

Garcia was lucky; some doctors end up having to live with serious consequences of a poor self-diagnosis. As a young gastrointestinal oncologist specializing in colorectal cancer, Dr. Dusty Deming found his dream job at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he would spend half his time caring for patients and the other half in a lab, developing treatments. But Deming was hiding an embarrassing problem: He had been bleeding from his rectum for nearly a year. Such bleeding is a classic symptom of colorectal cancer. Deming knew that, of course, but he also knew that the vast majority of people diagnosed with colorectal cancer are at least 55 years old. He was only 31. He assumed he had hemorrhoids, but he was reluctant to seek care for such an embarrassing condition.

It was only once the bleeding worsened and he struggled to have bowel movements that he finally signed up for a colonoscopy. During the exam, his doctor found a large tumor in Deming's colon. "We didn't even have to confirm it," Deming says. "As soon as they showed me the colonoscopy pictures, I knew what we were dealing with." Surgeons removed portions of his colon and inserted an ostomy, a permanent opening that leads directly from his colon to a pouch that he empties as it fills with waste. If he had visited a doctor when he first noticed the bleeding, he might have spared his colon.

But there is a silver lining. Deming says several of his patients who had refused surgery because they couldn't imagine life with an ostomy changed their minds after talking with him. "I actually can't think of a more rewarding thing," he says.

Deming now works with colleagues to develop treatments for specific types, or subtypes, of colon cancer. His lab uses genetically engineered mice to design personalized regimens for patients depending on the mutations in their cancers. He remains purposefully ignorant of his own subtype. "If I knew what subtype I had, that's probably all I would want to study," he says. "I think it's better that I not know so that we go where the science leads us and focus not only on curing my cancer but all patients' cancer."

Allison's personal experience with breast cancer also helped to orient her research—but in the opposite direction. As she underwent radiation, six months of chemotherapy and a double mastectomy, Allison continued to research HER2-positive breast cancer and to perform her duties as director of breast pathology for the University of Washington Medical Center. She also took Herceptin for a year. Not all women with HER2-positive cancers respond to the infusion, but Allison did.

She remembers well, though, what it's like to wait anxiously to see if a treatment will work. That's why today she is focused on fine-tuning the way that pathologists classify the 5 to 10 percent of women with cancers that have borderline or unusual HER2 test results. It's also why she keeps transparencies of her own breast cancer hanging in her office today. Every slide she creates, she says, represents a patient whose treatment is shaped by the decisions she makes.