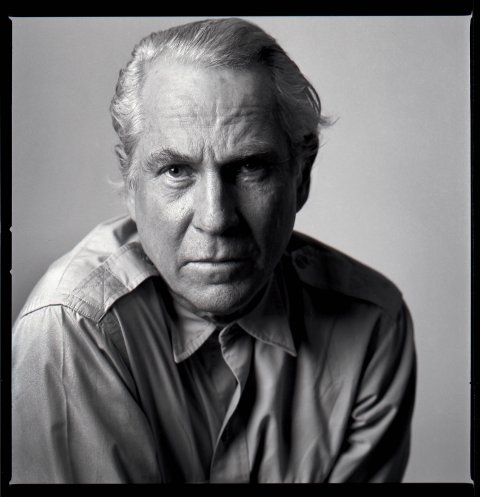

Gordon Lish is a traveler from a country no longer extant, a country where editors were princes and writers kings. A country where the publishing fiefdoms of Manhattan were proud castles in the sky, where the desperate flailings of The Real Housewives of Pittsburgh never made the gossip pages, but the seating arrangements at Elaine's always did.

In the 1970s, at Esquire, Lish was "Captain Fiction." He then spent almost two decades at Knopf, publishing the likes of Don DeLillo, Cynthia Ozick and Barry Hannah. With his risen cheekbones, flowing hair and linear mouth, Lish resembled one of the patrician squires he encountered at Andover, not a Jewish milliner's son from Long Island. He drank with the best of them and, when drunk, said things that were often cruel and sometimes true. Today, his refrigerator is full of Beck's.

"I live in the dark," Lish says by way of welcome. This is less a metaphor about senescence (Lish is 80) than a statement of fact. A chronic skin condition, psoriasis, keeps him indoors and out of sunlight; nearby Central Park is verboten. His apartment is a crepuscular chamber, largely unchanged since his wife died more than a decade ago. With his heavy knit sweater and wild white hair, which culminates in a braid, he wanders these rooms looking like some cross between an old fisherman and King Lear.

Yet the years have not dulled his edges. "How much time do we have to spend together?" he growled when I called to arrange an interview. A week later, we are drinking root beer as Lish recounted ancient skirmishes: how he has never forgiven Tom Wolfe for failing to blurb his 1983 novelistic debut, Dear Mr. Capote; how he sued Harper's, successfully, for reprinting a grandiloquent letter Lish sent to his seminar students; how he denied the future New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani a seat in his class at Yale.

Nor is he shy in waging battles new. Lish dismisses Philip Roth's assertion that literature has been eclipsed by a "voraciously consumed popular culture": "Roth is full of shit," he says without hesitation. Jonathan Franzen is undeserving of his reputation, as is Jonathan Lethem. The postmodernist Lydia Davis is "ridiculously overrated." Paul Auster, too: "I can't read him anymore." The subtle redesign of The New Yorker has been a "dreadful error." The upstart Brooklyn lit mag n+1 is a "crock of shit."

Thus spake a not-exactly-nice Jewish boy from Hewlett, New York, whose family owned a hat company in the Garment District of Manhattan. Lish worked as an errand boy, but was fired after a single summer. The ladies hat business recovered, as did the self-regard of young Gordon. He got into Andover and out of New York's Yiddishkeit confines. The colony of WASPs made him "thoroughly envious" when he saw them reposing on the school's lush lawns. "I looked upon these young men as creatures from elsewhere." He would behold with similar admiration, later, Paris Review editor George Plimpton, whose askew neckwear signaled an effortless grace.

Lish's sojourn at Andover ended after he fought a classmate who called him a "dirty Jew." More formative was a stint in the "bug house," occasioned by an adverse reaction to the hormone ACTH, intended to treat his psoriasis. At this Westchester mental institution, he met the ailing poet Hayden Carruth, who would become a mentor, according to Raymond Carver biographer Carol Sklenicka.

Lish attended the University of Arizona, only because he had already been sent to Tucson for his psoriasis. He later taught high school in Northern California, but incurred the administration's ire for "wearing a hat indoors, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance too quickly, allowing students to ignore duck-and-cover drills, having 'funny furniture' and abstract paintings in his house, and recommending the ideas of Emerson," writes Sklenicka.

It was in the wake of his departure from the classroom that Lish met Carver: The two worked across the street from each other in Palo Alto, California, the future editor toiling on a grammar tract and other texts for Behavioral Research Laboratories, the unknown writer then hacking away for Science Research Associates. They became bibulous buddies, but Carver left for Israel in 1968, while Lish was hired by Esquire to edit its fiction section in 1969, on nothing more than the strength of letter he wrote to editor Harold T.P. Hayes.

Thus a triumphant Lish came back East. Tom Wolfe recalled that the Gordon Lish of that time was "a very dapper and presentable fellow…and at the same time just the sort of maniac who is capable of perpetuatingEsquire's carnival of contrariness," as quoted by Esquire historian Carol Polsgrove.

"I was drunk all the time," Lish says now of the Esquire days. "I was looking for a fight." Lish declined to publish staples like Roth and Saul Bellow, writes Polsgrove in It Wasn't Pretty, Folks, but Didn't We Have Fun?: Esquire in the Sixties, while publishing the first major-magazine story by Carver ("Neighbors," 1971).

Thus began a relationship that has defined Lish's career, an association of which he once boasted but now cannot escape. He made the first two Carver collections (Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? and What We Talk About When We Talk About Love) far better than they had initially been, pioneering a style that has come to be known as "Kmart realism." But by some estimations, the next two (Cathedral and Where I'm Calling From), published with diminished influence from Lish, with less silence and more feeling, were even better.

By the time Carver died in 1988, he was regarded as the finest short-story writer of his time, studied like the catechism in fiction classes. But the question of Lish remained. I learned of him as the sort of purifying fire every work of fiction needs. In an undergraduate fiction seminar, a professor who had known Carver had us read "The Bath," about a young boy hit by a car on his birthday, alongside an earlier draft of the story, pre-Lish, which Carver called "A Small, Good Thing." Carver's version is bathetic and bloated, while "The Bath" buffets you with cross-currents of strange pain. The lesson was clear: Darlings were born to be killed by editors like Lish.

That wasn't how everyone saw him, though. A couple of years before I'd first encountered Carver, New York Times Magazine writer D.T. Max traveled to Indiana University, to whose library Lish had sold his papers. There, he found the fullest evidence yet of how deeply Lish's scalpel had cut. In 1981's What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, "Lish cut about half the original words and rewrote 10 of the 13 endings." Even though Max concedes that "some of the cuts were brilliant," the narrative of an alcoholic backcountry Chekhov hobbled by a domineering New York editor, only to regain his literary selfhood late in life, became the prevalent leitmotif of the Lish-Carver tango.

Lish is acutely aware of the controversy, and it still pains him. Carver's stories, he says, "were de-feebled by my exertions." Carver, he tells me, was "a fraud. I don't think he was a writer of any consequence."

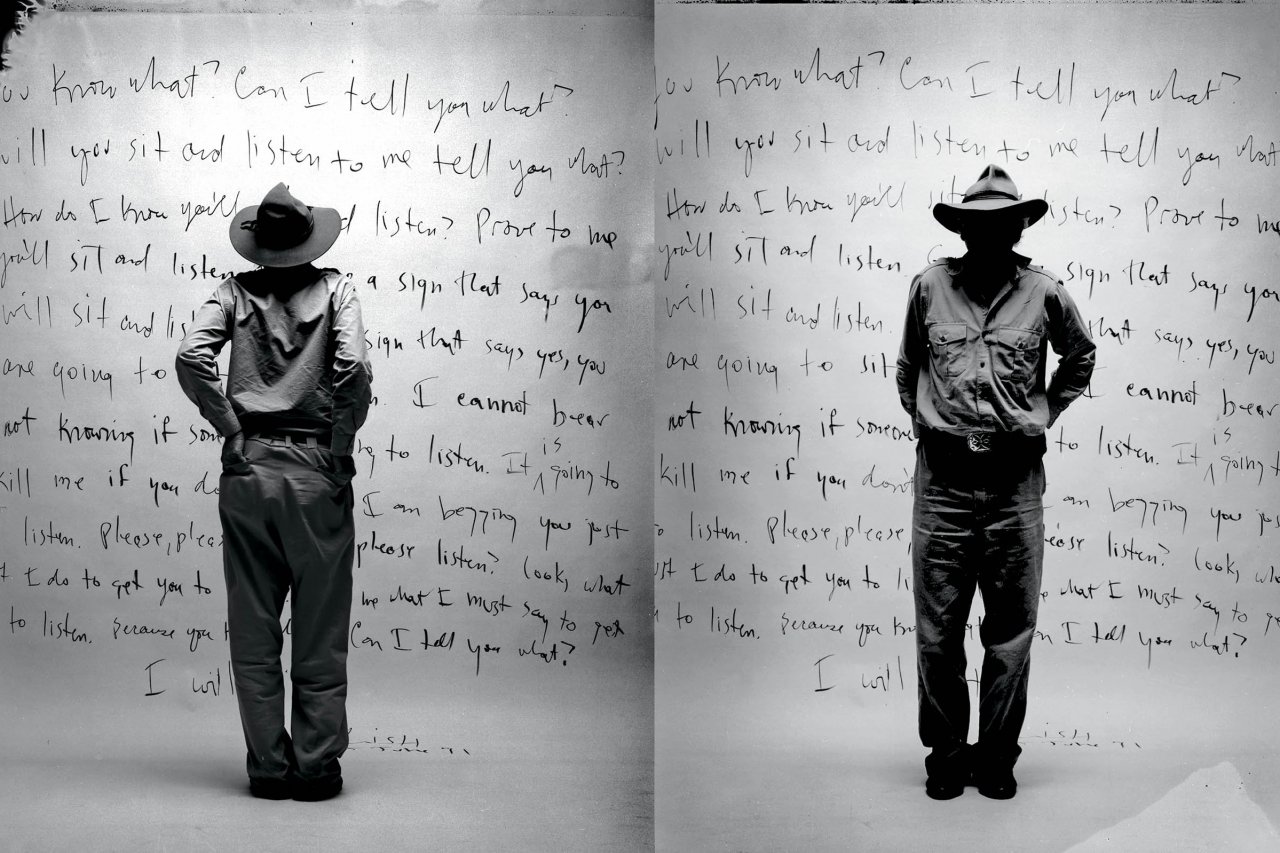

Whether Lish is a writer of consequence remains unclear. An editor at Knopf from 1977 until 1995, he is today persona non grata at the Big Five publishers, whose energies are largely devoted to finding new shades of grey. Nevertheless, Lish's short stories continue to be published by the boutique New York press OR Books, which released his Collected Fictions in 2010. A few of these stories have been formed into diamonds; some remain coal. Among the standouts is "For Jeromé—With Love and Kisses," in the form of a pleading soliloquy from J.D. Salinger's father to his inexplicably reclusive son. Others are inchoate, rife with voice—always the voice of Lish—but without the other qualities that make for great fiction.

The OR Books edition of Collected Fictions features a blurb from DeLillo, a longtime friend of Lish's. "What I find most impressive about Gordon is the work he did on his early novels," DeLillo told me. He laments that Dear Mr. Capote, along with the later Peru and Zimzum, are little read today. "I think those are very fine works of fiction," DeLillo says. "I don't think they got the attention they might have received" if Lish had not engendered so much controversy with his behavior. Then again, Lish dove into controversy the way a cormorant dives into oceans. It could have been no other way.

Younger littérateurs are curious about Lish the way you might be about a red-sauce joint that survives in some hip enclave. Jason Diamond, who founded the literary website Vol. 1 Brooklyn, says Lish is "one of the most important living figures in contemporary American literature." A recent article in The Guardianpraised Lish's "unique contribution to fiction…a wealth of avant-garde prose, worthy of the pioneers of literary modernism."

The Guardian also notes a third aspect of Lish's legacy: that of a writing teacher who nurtured talents as varied as the playwright Will Eno, the poet Victoria Redel, comic novelist Sam Lipsyte and experimentalists like Ben Marcus and Gary Lutz.

"Gordon Lish taught me to write," Lipsyte told me. "He would catch things in our prose we didn't know were there. He taught us to listen to ourselves." Redel was similarly effusive, countering the myth that Lish was "a guy always saying no, slashing paragraphs." He was, to her, "the great sayer of yes."

In a lecture delivered to writing students at Columbia in 2008 and reprinted in The Believer, Lutz said that Lish favored writing "in which virtually every sentence had the force and feel of a climax…a definitive inquietude." That Lishian strangeness lurks in the repetitive title he gave to Carver's first collection, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?

There are detractors, too, and not just in Carver's camp. Carla Blumenkranz, an editor at n+1, recently published a piece for The New Yorker's book blog called "Seduce the Whole World: Gordon Lish's Workshop." She concludes that Lish "asked students to write to seduce him, and when female students succeeded, he often took them to bed." Blumenkranz argues that Lish was better at discovering talent than nurturing it.

The New Yorker piece infuriated Lish. He told me that he slept with only one of his students, Amy Hempel, and that their protracted affair was no secret. Lish says he considered suing Blumenkranz, but decided against it. When I relayed these complaints to Blumenkranz, she said she remained confident about her research. But she added that he is a "fantastic storyteller" whose works teem with "extraordinary voices."

"I don't think there's ever gonna be a consensus on Lish," says longtime Doubleday editor Gerald Howard, who once worked on a Lish novel called My Romance, an ambitious but hapless project that sold poorly. Howard, who also had the unenviable task of editing David Foster Wallace, says the Carver cuts were both unforgivable and necessary: "He shouldn't have done it, but he did it, and it was wonderful."

The problem with Lish is that he is all over the place. That also happens to be the best thing about him. He was a brilliant dabbler, a studious dilettante. He knew everyone, tried everything. But his most lasting contribution may be the most troubling.

On July 8, 1980, after reviewing the manuscript for What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, an astounded Carver wrote a letter to Lish, essentially begging him to back off the savage cuts he'd made. Before that, though, he expends hundreds of words praising Lish: "You are a wonder, a genius, and there's no doubt of that….You've given me some degree of immortality already," Carver wrote. He was right about himself. Maybe about Lish, too.