In May 2014, measles was at a 20-year high in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that there were 288 identified cases—and counting. This is particularly dismaying news since the highly contagious disease was declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000.

However, citizens of two states need not worry that the dangerous illness would infiltrate their communities: Mississippi hasn't seen a measles outbreak since 1992; West Virginia can count back to 1994. That's because neither state permits children to enroll in kindergarten without getting their full roster of vaccines—no matter their parents' personal or spiritual beliefs. Critics of the states' unusually strict school vaccine mandates regard them as unfair, and the ensuing debate often boils down to a constitutional battle between religious freedom and equal protection for all. So it's a little ironic that two of the most conservative Bible Belt states in the country are the outliers here.

Measles—and other vaccine-preventable diseases like whooping cough and tetanus—periodically surge in communities where high percentages of parents decide not to fully vaccinate their children. That's why health officials and pediatricians all over the country eye Mississippi's and West Virginia's draconian vaccine mandates with envy. "People assume we must be wrong since the other 48 states allow [nonmedical vaccine exemptions]," says Jeff Neccuzi, the director of West Virginia's immunization program. But, he argues, they're the ones who have it right.

Mississippi's and West Virginia's strict requirements were instituted in the late 1970s, when West Virginia prevented any children from entering kindergarten without vaccines, except for rare medical exceptions. In Mississippi, a state Supreme Court judge did not mince words in 1979 when he overturned a short-lived exception granted to parents ideologically opposed to immunizations: "To the extent that [vaccines] may conflict with the religious belief of a parent, however sincerely entertained, the interests of the schoolchildren must prevail."

Meanwhile, other states began to permit exemptions. As health officials fearfully watched their states' kindergarten immunization rates drop over the past few years, some have pushed to make exemptions more difficult to obtain.

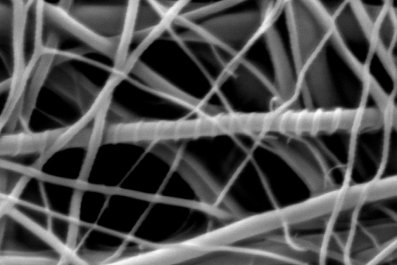

In Washington, where until 2011 parents only needed to sign an exemption form, up to a quarter of children in some counties opted out of vaccines. After the law was changed so that the form required an authorized health care provider's signature as well, the state's exemption rates immediately decreased by a quarter. Health officials in Colorado have proposed a requirement that would force parents to obtain a doctor's signature, or complete an online education course, before they say no. Thus far, their attempts have failed. The state has one of the highest exemption rates in the country. Whooping cough was found to be 90 percent more common in Colorado and other states with easy ways to opt out of vaccines than in places with stricter policies.

Zero tolerance for exemptions of belief, as is the case in Mississippi and West Virginia, might solve the problem of unvaccinated kids, but Walter Orenstein, associate director of Emory University's Vaccine Center, says "it has the potential to backfire and trigger even more anti-vaccination sentiment." The Association of Immunization Managers, based in Rockville, Maryland, agrees, recommending that states with exemptions for personal beliefs work to restrict them, instead of abolishing them.

So why didn't rigid mandates backfire in Mississippi and West Virginia? For starters, inertia. While communities of parents who opt out of vaccines have grown in other states, they never really got off the ground where exemptions for belief weren't allowed. What's more, there's a long history of public health involvement in the Deep South.

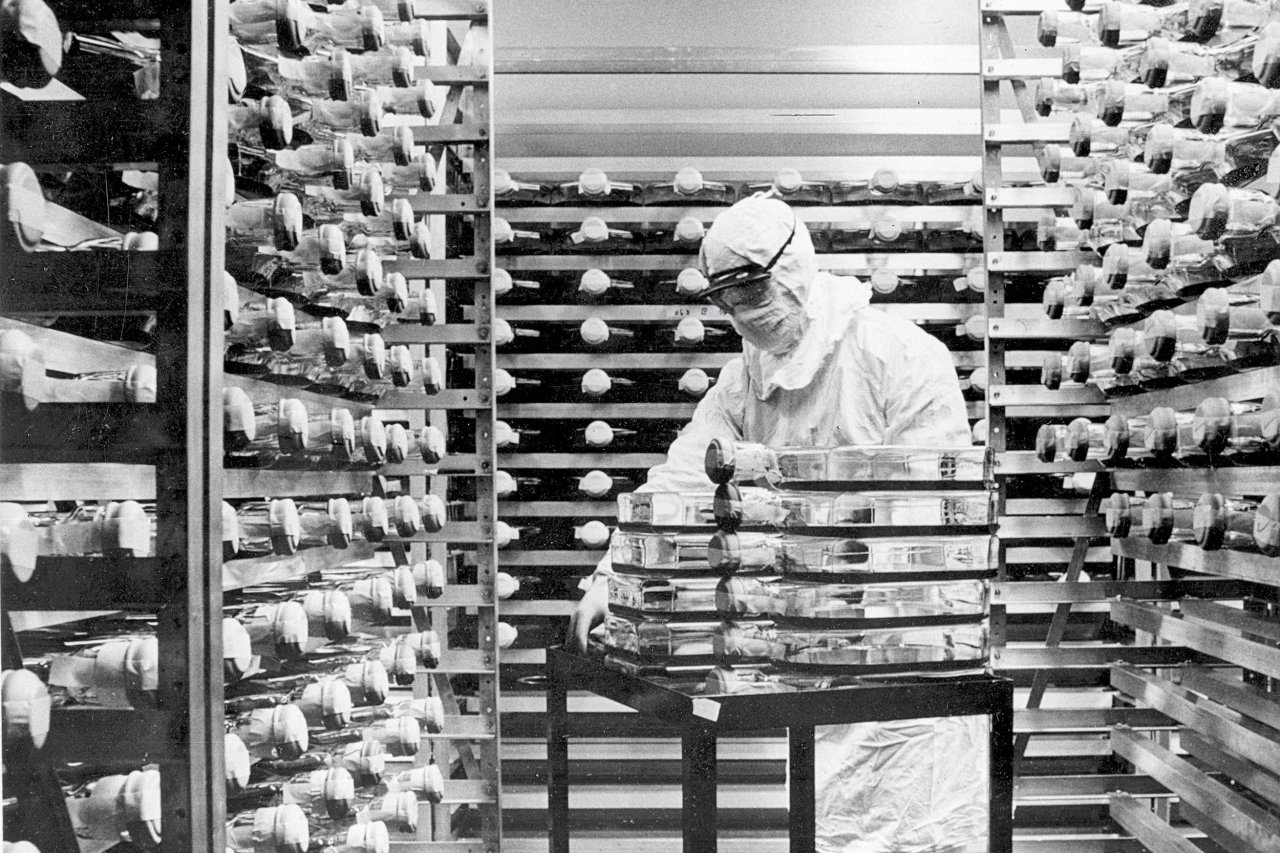

With high rates of poverty and a hot and humid climate ripe for plagues like hookworm, state governments sponsored numerous public health efforts to control epidemics throughout the first half of the 20th century. In Western and Northeastern states, health care was more frequently offered through a patchwork of private providers. The partnership between health departments and legislators in the South persisted through the 1970s, when most school vaccination mandates were launched. Alton Cobb, the state health officer in Mississippi's public health department between 1973 and 1993, says he worked with politicians to ensure that even the most remote, poverty-stricken families—"children in every little hamlet"—got the shots they needed. "We'd present legislative leaders with information to show the need and justification for a program, and we gained the necessary legislative action."

Meanwhile, at least eight states relaxed their vaccine requirements in 1999, following medical researcher Andrew Wakefield's infamous report that blamed autism on the MMR (mumps, measles and rubella) vaccine. Wakefield's study was shown to be fraudulent and retracted, but states did not reverse their laws.

Today, Mississippi has the highest rate of vaccination in the U.S., with 99.9 percent of kindergartners receiving their MMR. West Virginia's at 96.3 percent, above the national average, 94.5 percent.

However, West Virginia's rate for 19- to 35-month-olds is the worst in the country, at 84.6 percent. That may be because some people in the state live far from clinics, so when the vaccines aren't required by law, many parents skip trips to their doctor because they don't have the money, time or inclination to travel, Neccuzi says.

Poor access to health care also means that outbreaks fester before they are contained. They move swiftly even in affluent communities like those in San Diego, where 75 percent of the children who contracted measles during a 2008 outbreak were intentionally left unvaccinated. Many counties in Mississippi and West Virginia would likely require heavy federal assistance if an outbreak hit, because the states rank among the poorest, says Neccuzi. Cost is one of the arguments he made when promoting West Virginia's strict mandate in the face of proposals to change it.

Yet the lawsuits from parents who wish to opt out keep coming, and so do bills to introduce exemptions. Lindey Magee, a mother in Mississippi, has written bills (with help from the National Vaccine Information Center, an anti-vaccination advocacy group) that, if passed, would allow personal belief exemptions; Magee's bill died for the second time in the House this past April. She says, "We will fight harder than ever next year."

Magee homeschools her two children because she has to; they have not received all of their immunizations. Her personal belief—which would get her an exemption in many states—is that the full course of some vaccines could harm her children more than the diseases they prevent. Like many parents reluctant to immunize their children, Magee trusts her intuition (and information she finds on the Internet) over the advice of pediatricians. "I saw the Disney movie Bears, and if God gave bears instincts to survive their harsh reality, then human beings certainly have the instinct to protect children," she says. "Mumps, measles and rubella do not scare me," she adds, despite having heard that measles kills about 450 people each day around the world.

Pediatricians and epidemiologists in Mississippi and West Virginia worry that their states' high level of protection from vaccine-preventable outbreaks will diminish if parents can opt out. Magee counters that most parents will not take advantage of exemptions, but that hasn't been the case in other states, where the number of people who apply for them grows. Although the vast majority of parents in the U.S. continue to vaccinate their children, exemption rates doubled between 2006 and 2011.

Yet 2014's measles revival may also be a tipping point in vaccine exemption laws. Although the public outcry for opting out is louder than ever, most legislators aren't bending. Of the 31 proposals to expand exemptions presented in the U.S. last year, zero were enacted into law. Meanwhile, three of the five bills that make opting out more difficult passed. Raheel Khan, president of West Virginia's American Academy of Pediatricians, vows to fight bills that would loosen enforcement in his state. "I don't want to go through the experience of other states, where they are now seeing outbreaks," he says. "It's not a civil liberty to drive 100 miles per hour; that puts other people at risk. Vaccination is also a public safety issue."