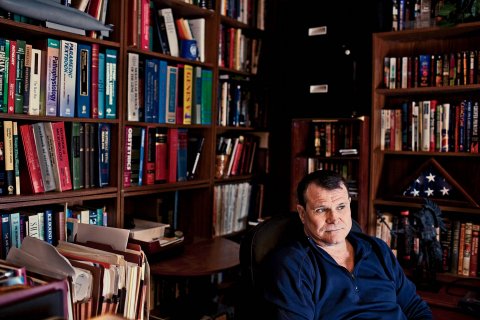

Steven Hatfill and I were sitting near a balcony overlooking a hangar of bomber jets arranged by war. We had wandered for hours across the vast aerospace gallery of the Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. Hatfill—doctor, ex-Army private, ex-expatriate—relished the chance to kill time among these engineering marvels, and the place seemed to activate his inner gearhead. After co-piloting a Wright brothers' flight simulator and exhausting the museum's exhibits, we moved upstairs for lunch. Leaning back in his chair, Hatfill pulled out a tin of Copenhagen tobacco and packed his lip. We got to talking.

"Let's make sure this is a nice article," he said, calmly.

Caught off guard, I stammered. "I—I—I can promise I'll be fair."

"I've been generous with you," he said. "And I've had enough shit."

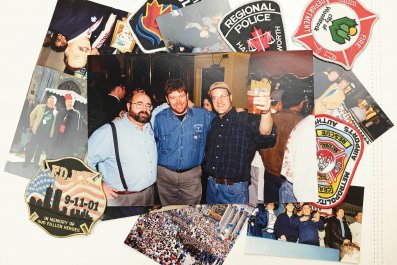

Hatfill had been generous, blocking out two days to guide me through his home and haunts in Washington, D.C. He rarely made time for reporters, and for good reason. A decade earlier, major and minor media outlets—dailies, glossies and obscure blogs—had falsely linked him to an act of domestic terrorism. The accusations sprang from government leaks, laced with post-9/11 paranoia. It took Hatfill a decade of lawsuits to settle the matter, but by the fall of 2010, he had begun sinking his legal winnings into a project that could wash away the libel and restore his reputation.

He had drafted schematics for a floating scientific laboratory of sorts, a ruggedized R&D ark that he called the Beagle III. Upon launch, the 126-foot-long riparian boat would journey to the Amazon or Borneo, where a crew of scientists would fan out across the rain forest and scour the soil and treetops for novel plant life. Then, aboard the vessel, they would catalog their samples, apply genetic rigor and—ideally—patent new drugs to combat emerging illnesses. "My life was interrupted, not by my own fault," Hatfill said. "This is a good replacement."

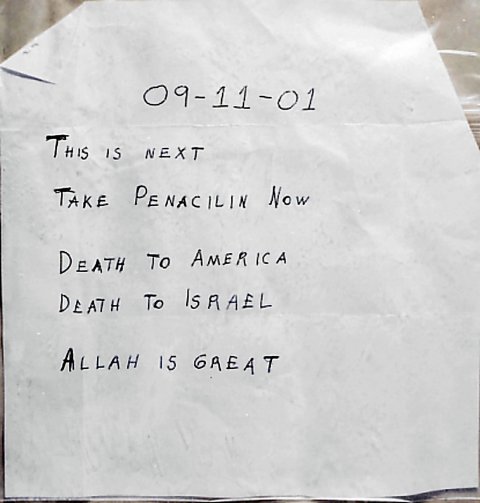

But that October, when I came east for a preview of his venture, the grievances of the past still hung in the air. In the wake of September 11, 2001, envelopes packed with a refined white powder showed up in the mailrooms of several U.S. news outlets and lawmakers. Some who handled the contaminated letters, which threatened "Death to America," developed blisters and skin lesions. For others, the spores dispersed like aerosol and clung to the lymph nodes before hitting the vital organs. When the dust settled, five people had died, and 17 others were sickened. To medical investigators, the symptoms smacked of anthrax, a weapons-grade bacterium, and the FBI began to short-list several government insiders as possible suspects. But on August 6, 2002, when Attorney General John Ashcroft went on CBS to discuss what the FBI had dubbed Amerithrax, he singled out only one "person of interest"—Steven Hatfill.

The surreality show was already well under way. Days earlier, reporters had camped outside Hatfill's apartment as the feds tore it apart. Quoting an anonymous law enforcement official, Newsweek reported with no apparent skepticism that bloodhounds with the scent of anthrax on their noses "went crazy" in Hatfill's presence. The FBI drained a pond in Maryland in pursuit of underwater evidence but found only silt. The language of forensics lent the coverage an air of empirical truth. But nothing quite added up. For one thing, Hatfill had never worked directly with anthrax. He wasn't a bacteriologist, after all; he was a virologist, an expert in hemorrhagic killers like Ebola and Marburg.

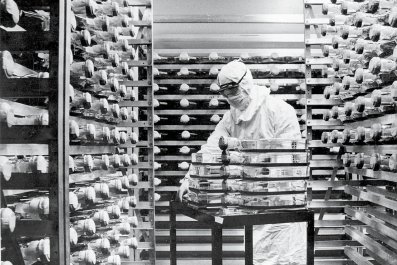

At the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), Hatfill had distinguished himself as an atypical bench scientist. To peers and the occasional journalist, he waxed dystopian about the threats of bioterrorism. At a conference in the late 1990s, he sketched out a concept for a network of triage trains that could shuttle victims and corpses out of a city under siege. He also wrote a novel, wherein a one-man sleeper cell unleashes a homegrown pathogen inside the Beltway. After leaving USAMRIID in 1999, he took a job at Science Applications International Corp., a private defense and intelligence contractor, where he designed training curricula for government agencies.

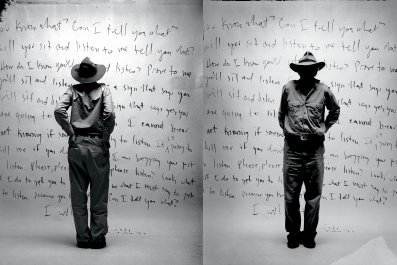

In the absence of evidence against Hatfill, stories about his past devolved into tales of questionable veracity. Nicholas Kristof spun out a series of columns in The New York Times that elliptically referred to Hatfill as "Mr. Z," a cipher from the "shadowy world of counterterror and intelligence." Don Foster, a "literary forensics" expert from Vassar, asserted in a 10,000-word Vanity Fair article that Hatfill was basically a "rascal" who palled around with bioterrorists. (At least one allegation survived scrutiny: a Ph.D. in biology Hatfill had claimed on a mid-'90s résumé turned out to be forged, one of his attorneys later confirmed.) And on the fringes of the online publishing universe, scraps of disinformation were used to flesh out elaborate conspiracy theories.

Hatfill mounted a vigorous defense. He recruited a boisterous talk-radio host named Pat Clawson to serve as his spokesman and suited up for two press conferences to declare his innocence. But his voice, scratchy and trebly, could not drown out the speculation, and his career was in tatters. So he turned to the courts, with mixed results. A judge dismissed his case against Kristof and The New York Times, and an appeals panel upheld the ruling, saying Hatfill had "voluntarily thrust himself into the debate." But in a $10 million libel suit implicating Foster and Vanity Fair he prevailed; publisher Condé Nast settled for a confidential sum, and the magazine printed a retraction (as did Reader's Digest, which had adapted Foster's essay). Former attorney general John Ashcroft also came to eat his words. In 2008, the Department of Justice officially exonerated Hatfill and agreed to pay him $5.8 million in damages.

But outside the media's gaze, a grenade thrower was still hiding in the shadows. Across a series of blogs and far-right message boards, someone going by the moniker of "the Real Luigi Warren" (a.k.a. "Luigi 'Anthrax' Warren") had operated a lurid rumor mill about Hatfill for more than a decade—promoting, in particular, hearsay about the years he lived and worked in southern Africa during the throes of apartheid. In 2010, after the aggressor surfaced in the comments section of theatlantic.com, Hatfill's lawyers made their move. They sent a six-page letter to the man they assumed to be the real Luigi Warren, a stem-cell researcher at Harvard Medical School named, not incidentally, Luigi Warren. They gave him 14 days to delete the online attacks or have his "reproachable conduct" exposed in litigation.

But Warren flipped the script. In fact, he had been a prolific post-9/11 commentator on his own woolly blog, The Hatfill Deception, where he posited that "the campaign to promote Steven Hatfill as a 'person of interest'…was a bureaucratic ruse or diversion to maintain a useful strategic ambiguity." But Warren said to Hatfill's attorneys that he was not the source of the latest diatribes against Hatfill; someone, he said, was impersonating him. In a quest to triangulate their way to the troll, whoever it was, Hatfill's attorneys roped Google into the lawsuit. The company eventually cooperated, handing over the IP address behind the "Luigi Warren" blogs, hosted by Google's blogspot. That numerical fingerprint—142.232.65.7—was traced to a computer in South Africa, at Stellenbosch University, where Hatfill had earned a master's degree and completed a medical residency in the early '90s. School officials reported that the machine in question belonged to a radiation oncologist named John Michie. The defendant agreed to a confidential settlement. (Michie did not respond to an interview request from Newsweek; Hatfill voluntarily dismissed Google from the suit.)

Money can buy poetic justice, but a trail of half-truths and innuendo doesn't disappear on its own—not from conspiratorial minds, and certainly not from the Internet. For the foreseeable future, Hatfill would have to live with being remembered for something he didn't do. Like Richard Jewell, Wen Ho Lee and other innocents caught in a net of false accusations, he would have to write a new story. His boat was just the beginning.

"I apologize for the mess," Hatfill said as we trekked through a hallway of boxes and detritus at his suburban D.C. apartment, the same place where the feds and reporters had come a decade earlier to hound him. "I'm in the process of moving."

We settled in the living room, where the taxidermied face of a lion stared from a wall in mid-growl. Light slivered through shuttered blinds, and Hatfill began explaining the origin story of the Beagle III. Holed up here in 2004, during the height of Amerithrax scrutiny, he came across an article in Nature about the state of pharmaceutical research. Officials from the World Health Organization on down had long warned about an impending "post-antibiotic era," when superbugs would run unfettered, fueled by evolving bacterial resistance to overused drugs and Big Pharma's reluctance to develop new arsenals of treatment. Hatfill stared into this abyss, he said, and saw a solution in the shape of a portable riverine laboratory.

By 2010, the anthrax investigation had come to an unsatisfying coda. A government scientist named Bruce Ivins, whose guilt the FBI had proclaimed with total certainty, ended his own life before charges could be filed. Meanwhile, Hatfill lowered his profile, finding solace in his family and his "tribe"—an around-the-world cadre of doctors and soldier types. He landed a position at George Washington University as an adjunct assistant professor of emergency medicine. The arrangement allowed him to escape for long stretches of time. He flitted between military bases, where he trained outgoing Navy SEALs and others in battlefield triage. And he increasingly decamped to Puerto Rico, where he had installed a kind of military Outward Bound in the rain forest. At the time, his professional life was fragmented and itinerant.

"When the present conflict ends," he told me in 2010, referring to the war in Afghanistan, "I can stand back with a good conscience."

Hatfill handed me a stack of documents marked "appendix." On the cover, a serpentine double helix shrouds a wireframe Earth, encircled by the acronym ABSOG—short for Asymmetric Biodiversity Studies and Observation Group, a not-for-profit trust Hatfill had established to support his pharmaceutical mission. I leafed through to find elevation maps, land surveys and blueprints for Hatfill's unbuilt, twin-diesel-powered boat. Inside the vessel's aluminum hull, he envisioned a plexus of laboratories, with DNA microarrays and other "space-age zuzu" for analyzing the genetic compositions of plants. Bedrooms would be equipped with video-conferencing systems and DVD players, and the executive cabin was modeled after the president's quarters on Air Force One.

For good measure, Hatfill had also thrown in a roof-mounted cosmic ray detector, which would switch on near the equator to capture data on "high-energy cosmic ray showers." An onboard chef from the ranks of Le Cordon Bleu would fuel a crew of scientists and trainees, and a 30-day supply of dehydrated food would hedge against disaster.

"What a great thing for a grad student," Hatfill told me. "Do some fieldwork, sit in a hammock, eat rice and beans."

But the expedition would be more than a semester at sea. Anticipating snakebites, dengue fever and other agents of death, Hatfill's schematics also include a surgical suite. The doctor emphasized that his E.R., staffed by a physician, would keep its doors open to people his crew encountered in the rain forest. He seemed sensitive to the appearance of colonialism, knowing his crew would be crossing into indigenous land. And this attitude seemed in line with his philosophy of counterinsurgency. "The military must establish loyalty with warlords, offering things that the enemy doesn't," he said. "But this requires the highest caliber of soldier, one who can be a friend of the villages and become part of their tribe."

Tribes came up frequently in our discussions, and in recruiting for his mission, Hatfill turned to members of his own. His initial hires for the Beagle III weren't scientists but veterans: an Army Ranger, a pararescueman, a "Selous Scout" from the formerly white-minority-ruled Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and a French Foreign Legionnaire. Their mission, according to Hatfill, would be "to keep scientists out of trouble and prevent them from getting lost."

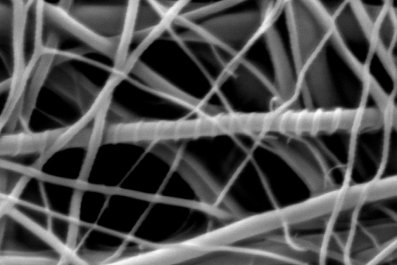

Wanderers from Colonel Kurtz to Percy Fawcett have lost themselves in pursuit of tropical grails. But Hatfill planned to go after something few others had sought—a class of organisms called endophytes. Dwelling in plants, these bacteria and fungi have shown medicinal promise for millennia. Three thousand years ago, Mayans treated intestinal ailments with a symbiotic organism on roasted green corn. In the late 20th century, biologists discovered that the bark of the Himalayan yew tree contains traces of a blockbuster chemotherapy drug, Taxol.

"There are at least a million unknown fungi in the Amazon, and more in Borneo," Hatfill said. "I need to go where bacterial World War III is being waged, where there's high biodiversity."

"It's either this, or retiring, getting Alzheimer's and dying," he added. So in lieu of a retreat, he was prepping for his WW III. Hatfill had allocated more than $1 million from his legal windfall to construct a full-scale "breadboard," or a prototype of the Beagle III—an idea he gleaned from a book called Out of This World: The New Field of Space Architecture. Then he would summon a shipbuilder to an undisclosed site in central Florida, down the way from a ranch where his parents once raised thoroughbred horses. Hatfill had purchased a colonial-style brick house in Marion County and was gradually moving his belongings from D.C. After nearly 20 years in the nation's capital, he was getting out.

Meanwhile, a cadre of Hatfill's soldier friends were awaiting a call to meet him in Puerto Rico. His property in the El Yunque rain forest sits in a gorge surrounded by mountains, shielded by a double canopy of trees. A lone dirt road snakes to the entrance, a few miles from the nearest town and a short drive to the world's largest single-dish radio telescope. Here, prospective Beagle III shipmates would soon come to learn essential survival skills. In July 2010, to test out Hatfill's curriculum, a group of businesswomen from the U.S. flew down for a "pilot course" led by some of Hatfill's guys. Among other activities, the trainees rappelled from a cliff and swam upstream through a rushing river.

None of ABSOG's board members—Hatfill's dad and three of his closest confidants—take a salary from their part-time work, according to copies of the organization's tax filings reviewed by Newsweek. But Hatfill has also established a for-profit corporation in Puerto Rico, called Templar Associates II. As his "appendix" puts it, Puerto Rico would serve as a wide-spectrum revenue generator, providing an "environmental testing ground for new tactics, techniques, equipment, and procedures for ABSOG's designated mission as well as for the U.S. military."

Hatfill was reluctant to go into details about the military side of his business, other than to say that the El Yunque is the most accessible rain forest in America's sphere of influence. For special operations forces, it's an ideal locale for jungle war games, for what used to be freely called Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape training before SERE became a euphemism for torture in the war on terror. (In response to a Freedom of Information Act request, the U.S. Special Operations Command said it had no open contracts with either of Hatfill's ventures as of 2012.)

On the Internet, Hatfill has managed to stay under the radar since the end of the Amerithrax saga. In 2011, he co-authored an article in the online magazine Small Wars Journal with his Selous Scout friend, outlining a Rhodesian counterinsurgency doctrine called "Fire Force." To future-proof against smear campaigns, he'd also parked himself on every imaginable Web profile site associated with his name. Why give bait to trolls, conspiracy theorists and free-range reporters? He'd had enough.

But in late 2013, Hatfill emitted a few new signs of life, in the form of a videotaped PowerPoint lecture called "Immediate Bystander" and a landing page for a series of novels he may be writing under the alias S.J. "Doc" H. By then, he had sued two of his original Templar associates for breach of contract, unjust enrichment, misappropriation of trade secrets and a host of other claims, after they allegedly used his camp and contacts to launch their own side business. And after my long hiatus waiting for a glimpse of his boat, Hatfill made it clear in October 2012 that I too had overstepped the boundaries. He asserted that everything we had discussed in person was off the record and directed all follow-up questions to his attorney.

Back in D.C., in October 2010, Hatfill and I were descending in an elevator at George Washington University, where he had just shown a class of premeds how to stanch wounds with tourniquets. Saying our goodbyes for the night, he reached into his pocket and offered to pay for my cab fare.

"Oh, no, that's not necessary," I said.

Hatfill looked up, holding his cash and smiling, and said, "At least let John Ashcroft pay for it."