What do you get when you cross the new Amazon Fire Phone with the rise of Etsy and the explosion of WhatsApp?

Big trouble for Coca-Cola. And, for that matter, misery for McDonald's, Ford, Gillette, Sony, Hilton, Calvin Klein, Kellogg's and every other mass consumer brand.

Brands were created to convey information about products at a time when it was hard for consumers to get information—before Al Gore invented the Internet. But our new hyper-networked and data-engorged era is killing the very reason for mass-market branding. This leaves big brands vulnerable to hordes of quirky little unbrands.

Today's technology gives the advantage to companies that have deep relationships with consumers, and there are two key ways to get those relationships. One is to gather so much data about your customers that you come to "know" them in a borderline-creepy automated way—that is the M.O. of platforms like Amazon or Google.

The other is to be small and intimate enough to connect with your customers on a personal level, like craft brands on Etsy or apartment owners who rent their places through Airbnb.

Coke, McDonald's, Ford and the like can't easily go in either direction. They're kind of hosed.

Relationships are why Amazon just introduced a phone when there are a lot of good phones out there. If one way to have relationships is through data, then more data equal better relationships. And that means a company like Amazon wants more ways to suck data in from customers. It flips the old mass-market brand model on its tuchus. Instead of broadcasting information out to as many people as possible, the best models today are like digital black holes exerting a mighty gravitational pull on information.

To Amazon, all those iPhones and Samsungs are a layer between Amazon and the data it wants. Worse, those phones might guide Amazon's customers to an app that's not Amazon, which means some entity like Google Play might get your data instead. Anybody who uses an Amazon Fire Phone will send so much data to Amazon, the company will know you like a long-lost twin. "Fire Phone puts everything you love about Amazon in the palm of your hand," Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos said at the launch. Actually, though, it puts you in the palm of Amazon's hand.

At least Amazon has a way to attack the problem. Most mass consumer brands don't. You buy Coke or Gillette or Calvin Klein from retail middlemen, so the brands have no idea who their customers are. You don't give McDonald's any information about your french fry habits. Hilton has your name and credit card but probably not much more. And these brands don't have many ways to change the situation. A McDonald's phone? A Coca-Cola membership? Again—hosed.

Etsy sits on the flip side of consumer relationships. After years of operating as an off-kilter craft site (purse made from men's tighty whities, $25), the company took off in recent years. It has 1 million global sellers who raked in $1.35 billion in 2013. To listen to CEO Chad Dickerson, the key is that Etsy's sellers remain small and quirky and the site encourages personal communication between buyer and seller. "It has the feel of a farmers market instead of a supermarket," he says.

Its strength is in the relationships. Little sellers on Etsy don't have Amazonian data, but they're small enough to have real relationships with customers. As a platform, Etsy grows because of the cumulative effect of millions of real relationships.

WhatsApp is yet another twist on how much relationships will matter. When tech finance legend Mary Meeker gave her annual trends report a few weeks ago, she made a big deal about the lightning rise of global messaging systems: WhatsApp with 400 million users, WeChat in China with 355 million, Line in Japan with 280 million. They are all about close relationships—chatting and sharing with small circles of people, not hundreds or thousands of "friends" on Facebook or Twitter. Meeker's point: The trend represents "the ascendency of the phone book over the friend graph."

WhatsApp is making even Facebook look like a broadcast medium. To sell to a consumer going forward, you'll have to be so intimate that you're in the consumer's phone book. No wonder Facebook bought WhatsApp for $19 billion. It's the future of marketing.

In fact, in this new age of consumer information and relationships, a big brand can be a negative. A brand conveys consistency and safety; it says a can of Coke will taste the same whether you're in Syracuse or Saskatoon. As we get better information about small-scale competing products, we feel safe seeking out the unique, the undiscovered, the unbrands. Hilton becomes vulnerable to Airbnb's one-of-a-kind dwellings. Tiffany becomes vulnerable to jewelry makers on Etsy.

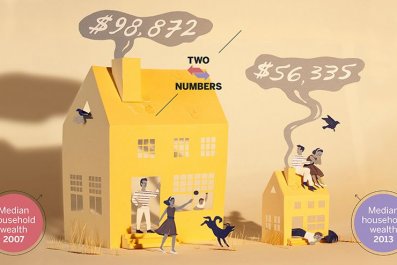

The result is a developing societal shift, as authors Itamar Simonson and Emanuel Rosen describe in their new book, Absolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in an Age of (Nearly) Perfect Information. We used to want the brands everybody else had. We're moving toward mass individualism, wanting stuff nobody else has.

Coca-Cola was the world's most valuable brand for decades. Last year, it fell to No. 3, behind Apple and Google. Coke is going to sink further unless the company can figure out a way to get the local bottler to pick up the phone when I call and customize a six-pack so it tastes like Mexican Coke with a hint of nutmeg. To borrow a line from an old competitor, next-generation Coke really needs to become the uncola.