Henry L. Marsh III wanted to see President Barack Obama's second inauguration in person because, at 79, he figured he might not live to see another black president elected. So the Virginia civil rights lawyer spent January 21, 2013, in Washington, D.C., witnessing a part of history he had dedicated his life to making possible.

His presence at Obama's inauguration, however, set off one of the dirtiest political maneuvers in recent history.

Marsh is a Democrat in the Virginia Senate, a chamber that until last month was divided evenly along party lines, with 20 Democrats and 20 Republicans. But with Marsh 100 miles away in Washington, Republicans briefly enjoyed a 20-19 majority, if only for a few hours. In a power grab so brazen it caught even the GOP governor by surprise, Senate Republicans passed a bill redrawing the state Senate map to give them a permanent majority.

By the time Marsh returned, his colleagues had passed a redistricting bill that would have vastly undercut the political power of black Virginians. The new map crowded black voters into minority-heavy districts so that up to eight more districts would turn red, a strategy political scientists call "pack and crack," leaving Republicans with a 27-13 majority in Virginia for years to come. As if to pour salt on the wound, this all happened on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The plan never made it out of the Republican-controlled legislature. Two and a half weeks after the Senate passed the new map, the Republican speaker in Virginia's lower chamber, after much reflection and prayer, angered his own party by killing the map with a procedural move.

"Count that as a new low for hyper-partisanship, dirty tricks and the unaccountable arrogance of power," declared The Washington Post, echoing the widespread shock at the sly incident that made a mockery of democracy.

That attempt may seem extraordinary up close, but take a step back to look at the changing demographics of Virginia and the South more broadly and this power play starts to make sense. Two months before, Obama had won the state for a second time. For the first time since 1964, Virginia was on its way from red to blue.

Virginia's Republicans were seeing decades of political control melting away before their eyes. "They tried to seize power that they didn't deserve," Marsh said. "They got caught with their hand in the cookie jar."

SOUTHERN EXPOSURE

To understand why the Republican Party has come to dominate the South—and why that strength may now be waning—you have to go back to the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln and Northern abolitionists ran the Republican Party in the 1860s, while the Democrats drew much of their strength from the slave states. After Reconstruction, when the Southern states were left to their own devices, the Democratic Party ruled with an iron fist—and Jim Crow. Their reign lasted nearly a century.

The GOP in Dixie, political scientist V.O. Key Jr. observed in 1949, more closely resembled a cult or a conspiracy than a political party. In 1950, of the 127 members of Congress from the former Confederate states, just two were Republican.

But the Democrats' stranglehold on the South was already loosening. Perhaps no one embodied, or facilitated, the South's transformation from the Democrats' Solid South to the regional anchor of today's Republican Party as much as Strom Thurmond.

After Democratic President Harry Truman embraced civil rights ahead of his re-election bid in 1948, Southern Democrats broke from the party in protest. They wanted to send a message to Democrats in Washington: Either civil rights go, or the South goes.

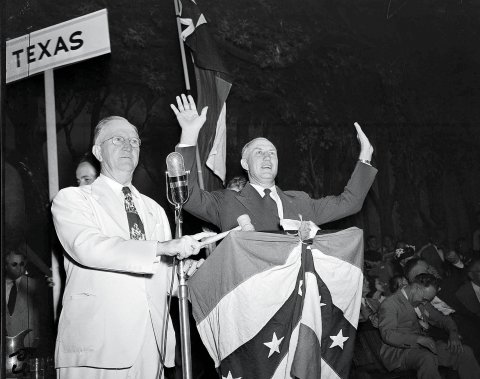

A group of Southern lawmakers formed the "Dixiecrats," who were devoted to states' rights, and nominated Thurmond, the former Democratic segregationist governor of South Carolina, for president. On a hot day in Birmingham, Alabama, Thurmond made his first speech to Southern deserters as their presumptive nominee.

"There's not enough troops in the Army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the nigra race into our theaters, into our swimming pools, into our homes and into our churches," Thurmond told them. That November, he won over a million votes and carried four states in the Deep South.

Thurmond and his fellow Dixiecrats weren't kidding around. Two months after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in July 1964, Thurmond, by then a U.S. senator, switched parties from Democrat to Republican. That November, five Southern states followed his lead and voted for Barry Goldwater, the Republicans' ultra-conservative presidential nominee. In 1964, more Southern whites voted Republican than Democrat for the first time. They never went back.

Johnson knew the landmark civil rights legislation would cost his party in the South. On July 2, 1964, he signed the bill, with soaring rhetoric about the moral imperative of the civil rights cause broadcast into Americans' living rooms. But that evening, according to historian Robert Dallek, one of his aides found him in bed, looking glum. "I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come," Johnson said.

Immediately after the Civil Rights Act, Southern states began to vote Republican in presidential elections. Led by the 1968 presidential campaign of Richard Nixon, Republicans came to the South with open arms, and white Southerners slowly accepted their embrace. Nixon needed the votes of the Southern Democrats who had defected to Goldwater four years before. But George Wallace, the segregationist former governor of Alabama and a former Democrat, was competing for those same votes as a third-party challenger. So Nixon turned to the man who could help him win the South: Thurmond.

Describing a meeting between Nixon and Thurmond in Atlanta in June 1968, historian Rick Perlstein described the "stark" choice before Nixon that day: "What kind of Republican Party would he propose to lead? One that was committed to the spirit of Lincoln? Or one committed to the spirit of Strom?"

The two came to an understanding: Nixon promised to stonewall school desegregation; Thurmond promised to back Nixon.

Wallace won five Southern states, but not enough to keep Nixon out of the White House. In 1972, Nixon continued his Southern Strategy and, aided by the absence of Wallace, who had been shot in May, won not just the South but nearly every state. When Democrat Jimmy Carter of Georgia won the South in 1976, it was the last time a Democratic presidential candidate would make real inroads there. In 1980, Ronald Reagan finished the job Nixon had started.

It was during Reagan's presidency that more white Southerners began to identify as Republican than Democrat. Soon, the South's preference for Republicans at the top of the ballot began to trickle to the bottom. In 1991, the Deep South was represented at home and in Washington by 27 Democrats and nine Republicans. A decade later, Republicans had an advantage of 24 to 12, much of the gains coming from packing black voters into a small number of districts. Of white Southerners who went to the polls in 2002, only 26 percent identified as Democrats. That helped Democrats maintain a lock on state legislatures in the former Confederacy from Reconstruction until the Republican-wave election of 1994, when the GOP took four statehouses. After Election Day 2012, Republicans seized all of them—save that pesky split Senate in Virginia.

THE OLD NEW SOUTH

At the moment Republicans fully realized their hold on the South, demographic change means the region's political future is once again in flux.

The South is undergoing rapid change. Five decades after the Great Migration, when 6 million blacks left the South for Northern cities between the end of World War I and the 1960s, African-Americans are steadily moving back to the South, and a growing number of Latinos and Asians are flocking there in search of jobs.

Between 2000 and 2010, the date of the last census, the black population in the South grew by 18 percent, to over 23 million. The South is now home to 57 percent of all black Americans, who make up at least 20 percent of the South's population. (The census defines the South as the 11 former Confederate states, plus the former border states of Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware, as well as Oklahoma.)

That decade also saw a dramatic rise in the Southern Hispanic population, which topped 18 million by 2010, while the Asian community hit 3.8 million, up 69 percent. While the South's minority population grew by 34 percent between 2000 and 2010, the white population grew by just 4 percent. By 2010, minorities made up 40 percent of the South's population.

This population boom has untapped political potential. As of 2012, there were more than 3.2 million unregistered blacks living in the former Confederate states as well as the former border states of Delaware and Maryland, alongside 3.3 million unregistered Hispanics and 759,000 unregistered Asians, according to a report by Benjamin Jealous, a former president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank.

These nonvoting minorities could shift the balance of power in nearly every Southern state if they register and turn out to the polls in significant numbers. That's because while white voters have increasingly migrated to the Republicans, minorities have gone to the Democrats. In 2012, Obama won 93 percent of the black vote, 71 percent of the Hispanic vote and 73 percent of the Asian vote. By contrast, he won just 39 percent of the white vote.

"There is no question that the South is going through a period of rapid and dramatic change—the demographics alone are just amazing," said Chris Kromm, executive director of the Institute of Southern Studies, a nonprofit research outfit. The question is no longer whether the South will change but how soon.

In South Carolina, registering 40 percent of that state's unregistered minority voters would mean enough new voters to upset the balance of power, according to Jealous's report. Up the road in North Carolina, registering just 10 percent could put Democrats in power. Georgia, Tennessee and Texas would turn blue if 60 percent of the unregistered minorities voted. "The future is really up for grabs," Kromm said.

In Georgia, Democratic state Rep. Stacey Abrams, minority leader in the House, is already reaching for that future. "The actual numbers say that the change is already here," she said. Now the goal is to "activate those numbers."

Earlier this year, Abrams started the New Georgia Project with the goal of registering the 800,000 unregistered minority voters. (GOP governors have won their last three races in Georgia with an average of just 260,000 votes.) The group's core staff of less than 10 registered 25,000 voters in the first three months., and the will try to register as many as possible before this November's crucial contest for the open U.S. Senate seat being vacated by retiring Republican Saxby Chambliss.

Among progressives, Abrams is a rock star. "Stacey in Georgia has been one who has demonstrated that she has a plan, she's been really focused, and she executed her plan while watching the state of Georgia transform," said Derrick Johnson, president of the Mississippi NAACP. "That's the only reason why we have a real contested Senate race in Georgia right now."

Abrams, Johnson, Jealous and their cohorts say that registering minorities is not primarily about helping Democrats retake the South but ensuring that all Americans are represented in Washington. But their project is inescapably partisan. Even half a century after the Civil Rights Act, as Democratic strategist Cornell Belcher put it, "you cannot have a conversation about the political South without a central part of that conversation being the understanding of race matters."

THE WHITE PARTY

In the era of the first black president, white Southerners have become even more Republican. In other words, as the South becomes more diverse, it has also become more polarized.

In 2012, a huge portion of the South saw more than 80 percent of white voters choosing Republican nominee Mitt Romney over Obama. When Republicans took most Southern statehouses in 2010, they used control of the redistricting process to cram minorities into a small number of districts, consolidating Republican control while drawing stark racial lines between the parties.

"In private discussions, Republicans in the South talk explicitly about their goal of turning the Democratic Party into a black party, and in many Southern states they have succeeded," wrote The New York Times's Thomas Edsall.

"African-American legislators make up the majority of state House and Senate Democratic caucuses in most of the Southern states."

Democrats need to stop "that retrenchment, that polarized digging in of certain swaths of the white electorate in order to be successful there," said Belcher, who worked on Obama's 2008 and 2012 campaigns. "It's not as though we've solved or put to rest the old ghosts that have historically haunted the politics of the South."

Perhaps nothing proves Belcher's point more than the flood of new restrictive voting laws enacted after 2010—voter ID requirements, registration restrictions, cutbacks on early voting days—that, studies show, keep minorities from voting. "Of the 11 states with the highest African-American turnout in 2008, seven have new restrictions in place," a recent report from the Brennan Center for Justice found. "Of the 12 states with the largest Hispanic population growth between 2000 and 2010, nine passed laws making it harder to vote."

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston set out to discover if the new laws really are a thinly veiled attempt to suppress the minority vote, as Democrats and civil rights advocates argue. They found that states with higher turnout among both minorities and poor people were more likely to pass restrictive voting laws, and that the rate of passage for these laws rose when the number of Republicans in the Legislature increased or when a Republican governor was elected.

"They wouldn't be doing this if they weren't very concerned about the impact that demographic changes will have on the power and the status quo from which they benefit," Jealous, the former NAACP leader, said of the Republicans. "We have to internalize what they understand, which is that every demographic trend for the next several decades is in our favor and that we are ultimately in control of how fast the future comes."

It's not just the future of the South that hangs in the balance. The South is increasingly the political center of gravity for the entire country, and it will push the entire country.

As the fastest-growing region of the country, thanks to the influx of minority populations, the South's political power is growing. After the 2010 census, Southern states gained seven congressional seats and seven electoral votes, while the liberal Northeast lost five seats and five electoral votes. Today, almost half of the 233 members who make up the GOP majority in the House of Representatives come from the former 11 Confederate states.

Control of the Senate this year is in the hands of Southern voters, who will decide close races in North Carolina, Arkansas, Louisiana and Georgia.

Democrats have made inroads in the South. Three former Confederate states have already trended blue in backing Obama: Virginia in 2008 and 2012, Florida in 2008 and 2012, and North Carolina in 2008. Pro-Democratic groups have begun turning Texas blue, largely by activating the state's huge Hispanic population. Optimistic Democratic operatives believe Texas could be in play by as early as 2020; pessimists think 2024 or 2028 is more realistic.

That's because changing demographics are not a magic bullet for Democrats or automatic death to Republicans. Without a massive influx of resources to register and engage voters, change could take decades, or never materialize at all. "Demography is not destiny. It merely points the direction the South is headed," Kromm said.

The Obama campaign invested in voter turnout, and it worked. In Florida, the NAACP registered 115,000 new voters before the 2012 election: Obama won by 73,000 votes. In North Carolina, the Obama campaign registered more than 250,000 before November 2012: Romney won by a hair.

The big question is whether the Democrats put massive resources into the South. In Texas, the large number of Latinos may make the state's political evolution seem inevitable, but connecting with voters and keeping them engaged costs millions.

"What we're not seeing is the Democratic Party saying, 'Hey, maybe forgo our umpteenth ad buy and invest in real organizing in the South," Jealous said. Running a presidential campaign in Georgia in 2016 will cost millions of dollars, and that money has to come from another part of the campaign.

"The conventional mathematics of Democrats' campaigns has to change," said Belcher, adding that Obama's campaign was not made up of the establishment types who prefer TV buys over registration drives. "More of those resources have to be moved toward expanding the electorate, which means also different infrastructures and vehicles for reaching and communicating with and touching that electorate have to be put in place and invested in."

Democrats seem to be waking up to this reality. Their committee responsible for protecting the party's Senate majority plans to spend $60 million this year on registration and turnout efforts in 10 states with close Senate races, including Georgia, North Carolina, Arkansas and Louisiana. "Yes, we have to be on TV," the committee's executive director, Guy Cecil, told The New York Times in February, "but we're not willing to sacrifice the turnout operation or the field operation to do that."

The Democratic National Committee released an innovative voter-registration tool in June that would allow state parties, campaigns and even third-party groups to locate unregistered voters in every precinct in the country. Meanwhile, much of the South is experiencing growing pains, with a younger, more diverse constituency clashing with the old guard currently in charge.

In Virginia, Senate Republicans failed to pull off their Martin Luther King Day ruse, but in June they took the majority when a Senate Democrat resigned. (Federal officials are investigating whether Republicans criminally bribed him to step down.)

In North Carolina, so-called Moral Monday protests at the capitol to push back against the Republican Legislature's ultraconservative agenda have become a phenomenon, spreading to Georgia and South Carolina.

"I think it's an exciting moment. You're seeing the renaissance of activism in this 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer," said the Reverend Raphael Warnock, a pastor at Martin Luther King Jr.'s church in Atlanta. Warnock and 38 other protesters were arrested at the Georgia state capitol in March for civil disobedience over Medicaid; the state's Republicans have refused to expand it under the Affordable Care Act.

The importance of this year's civil rights anniversaries makes the current moment one of optimism for the future. "I think quietly there is a movement waiting to be born," said Warnock. "That this year will be seen not just as a year that we looked back to see what happened 50 years ago, but we chartered a way forward."