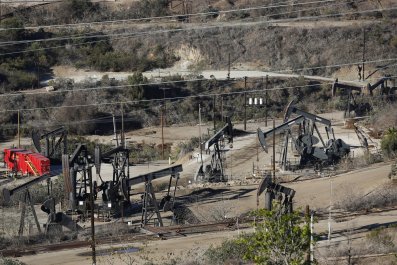

2014 is witnessing a proliferation of violence, or at least its threat. That's clear from the dissolving borders of Syria and Iraq, to the ongoing genocide in the Central African Republic, and from East Ukraine to the South China Sea.

Exactly 100 years on, the temptation, perhaps, is to explain this expansion in international violence through comparisons to 1914. That would be wrong, because war today is itself fundamentally evolving in the face of the information revolution.

To think about contemporary conflict through the traditional concept of war is often to follow a path that risks leading national security policies into dead ends. If we want peace, don't prepare for war; re-think it.

The traditional concept of war presumes that there are two sides, or two blocks of alliances, who present a clear enemy to each other to be defeated in battle. The idea of military victory makes sense in that context. Military victory sets conditions for the political settlement afterwards, marking a clear boundary between war and peace, geographically, chronologically, and legally. Armies know what their mission is in that context: to defeat the enemy.

But war has never been a static concept; it has evolved over time, mainly as a result of economic, social and political changes. The Industrial Revolution prefigured the industrialised warfare of the First World War. Today the information and communications revolution is shaping the two fundamental trends in modern wars away from the traditional model: first, fragmentation, and second, open-ended conflicts.

I

First, fragmentation: the general tendency is away from conflicts that are clearly one side against the other towards multiplayer conflicts in which several groups, ranging from the local to the international, kaleidoscopically compete against each other as much as participate in a two-way fight.

Fragmentation is not new, but its effects are radically catalysed by the speed and inter-connectivity of contemporary globalisation driven by the information revolution.

The information revolution encourages fragmentation because it simultaneously has the power to bring powerful networks together, and to break them up. Consider the Arab spring, in which a disparate range of people and of interests were drawn together by the simple and powerful desire to rise up against oppressive regimes.

But once formed, the information revolution catalysed the fragmentation of those networks once they started to disagree with each other, thus re-forming new groups. Look at how the Arab spring became the Arab winter; comrades in arms have been split by factional and religious differences.

Fragmentation profoundly affects any armed conflict that may well start as a relatively polarised fight, as people are drawn together under one cause – be it toppling Assad in Syria or Gaddafi in Libya – but soon fight amongst each other as much as with the original enemy; these confusing, complex, multi-layered patterns are replicated by each of the factions' regional and international backers. The convoluted evolution of who backs which of the mutating factions in Syria over the past three years, and now in Iraq, makes that clear.

The speed and ease of communications and of transport has radically changed how people in practice get to a war zone. That matters because it explains why the information revolution is about far more than the role of the media, or social media, in conflict.

Consider how easy it is for European citizens, for instance, to commute to fight in Syria via Turkey; all they need is a budget airline ticket, a smartphone, and a contact in one of the armed militias. People can participate in conflicts, directly or vicariously, as never before; they bring their own hopes and prejudices to the fight, swelling the ranks of one group, while others might branch off into a sub-faction.

Strategic problems arise when we treat conflicts that are actually fragmented as two-way wars, as we treat as a coherent enemy what are actually disparate groups, who cannot easily be defeated precisely because they do not fight, or fall, as one.

The war on terror is the classic contemporary example of a fragmented conflict. "The terrorists" actually turned out to be a series of franchise movements with no clear boundaries. In 2001 as in 2014, the agendas of jihadist groups vary significantly in line with local agendas.

In Afghanistan, for example, the idea that the terrorists were one "side" – with us or against us – led to a conflict in which the local political consequences of using force were obscured by the traditional idea of defeating an enemy in war: most of the "terrorist" Taliban turned out to be not a coherent force but a loose franchise of drug dealers and local tribes who were on their own side protecting their own interests, not al-Qaida's.

The strategic implication of fragmentation is that -conflicts which militarily and morally may initially appear clear-cut, like rescuing school girls in Nigeria, or simply bombing the Isis jihadists back from the brink of Baghdad in Iraq, rapidly become intensely complex decisions once the underlying tribal and sectarian complexity of any intervention becomes apparent.

II

Have politicians, diplomats, soldiers and policy makers grasped the consequences of fragmentation in war? It is hard to say. Look at just the past two months: there is plainly an inconsistency in the speed with which the US government rushed to declare Boko Haram a terrorist group, despite risking embroilment in the political quagmire of a Nigerian insurgency, and barely a month later, the restraint it showed in not bombing Isis because it realised that risked making an enemy of all Iraq's Sunnis, whom Baghdad have systematically marginalised since 2010.

More broadly, in fragmented conflicts the idea of a war's end point being marked by one side's victory starts to lose meaning, as there is no clear enemy against whom a victory can be defined. Rather, ongoing armed political rivalry between an evolving range of factions means that conflicts tend to merge into routine politics with no clear end point, as political competition does not end.

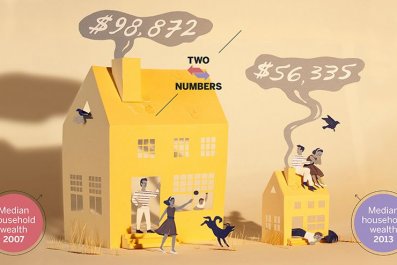

Take the war in Iraq during the US "surge" of 2007-08. Part of the campaign involved defeating al-Qaida, a clear enemy that was attacked and defeated, mainly in the suburbs of Baghdad, by coalition special forces. The outcome of that aspect of the campaign can legitimately be understood in terms of enemy killed or captured, consistent with the traditional military idea of defeating an enemy.

But the wider campaign was not trying to defeat an enemy, but to use both military and political action to stabilise Iraqi politics, particularly to bring the main Sunni groups within the ambit of the Iraqi government. The outcome of that campaign was not the body count but polling figures (or their equivalent).

As the outcome of the US surge was ultimately a given configuration of Iraqi politics, as politics doesn't end, that configuration was liable to evolve in an undesired direction, as it quite spectacularly has done in 2014.

Thus the line in fragmented conflicts between when a war ends and the peace starts is very hazy, as we see in Iraq today: it's not clear if the Iraq war is over or not.

When a war's outcome is better measured by political polling figures – how far the various Sunnis factions in Iraq support Baghdad's rule, for example – not body counts, there is little distinction between the use of violent and non-violent actions in a conflict. The risk is plainly that -military and political activity merge and, by consequence, war and peace also merge, encouraging open-ended -conflicts.

That applies not just to insurgencies, but state on state conflicts too. The situation in Ukraine is a case in point. The Russian leader, Vladimir Putin, has not been defining his outcomes in terms of defeating an enemy militarily.

Rather, Putin has been engaged in a conflict of coercive communications in which the success or failure of actions, both violent and nonviolent – be they Russian troop movements on Ukraine's border or Putin's TV statements, as well as violent actions by the pro-Russian groups on the ground – are measured more by shifts in polling figures and attitudes than casualty figures amongst the people the Russians seek to influence (primarily the various factions in East Ukraine, and governments in Kiev, Washington and European capitals, not to speak of his domestic audience). Call it armed politics.

The obvious question this raises for national security policy makers is how to maintain peace in conflicts of armed politics, given that despite the absence of war, the situation in Ukraine can hardly be characterised as peace.

The actual US response to the Ukraine situation helps answer this question. Resorting to clear-cut military action to defeat an enemy – the traditional form of war – to counter armed politics is an option. But it tends to raise the stakes to an extent that the risks rapidly outweigh the rewards; indeed, the US and Nato have not resorted to military force to counter Russian actions in Ukraine. The alternative is then to do nothing (the position, more or less, of some EU states); or to counter with armed politics of one's own, or similar methods of coercive communication, as the US has done in the form of sanctions to influence the behaviour of Putin and his inner circle.

III

The paradox and the danger of using armed politics, or its equivalent, is that it blurs the very line between war and peace that it seeks to uphold.

Why? Because war has much clearer geographical, chronological, and legal boundaries, which are based on where the military fight takes place. That allows for a distinction between military activity in war that aims to defeat the enemy on the battlefield, and subsequent political activity in peace. In this way war limits international violence and more clearly defines where and when states use violence against one another.

Conflicts characterised by armed politics, on the other hand, have blurred boundaries, because coercive actions, be they military or nonmilitary – the movement of tanks on the border, or TV statements, or sanctions – all too easily merge into routine international politics.

The risk is that if the scope of such conflicts is not limited by what is genuinely in national interests, the results are expansive conflicts that occupy a grey zone between war and peace, which set no clear limits to international violence, or at least its threat.

So for national security policymakers to maintain peace in conflicts of armed politics that by their very nature blur the line between war and peace is no easy task. The most common way to deal with international aggression outside of war is to mirror it, but with the caveat that without clearly limited goals, one risks being drawn into endless conflict that ultimately unhinges the very peace one seeks to establish. A hard balance to strike in practice: political leaders in such conflicts are all too easily accused of doing too little, or of overreacting.

While the information revolution is a fundamental evolution in contemporary conflict, war in its traditional form still exists. That is obvious from recent experience, whether we look at the Russian-Georgian war, fought with tanks, or the Sri Lankan civil war.

Nor is the nature of contemporary conflict entirely new, but merely a radical development born of the information revolution. Take the Cold War: as the name suggests, it was neither war nor peace; it lasted a long time because there was no clear distinction between the conflict and normal international politics.

Neither is the use of armed politics new. Terrorists planting bombs don't expect to defeat a state's army militarily, but rather to send a message that immediately achieves a political result; that has been the case for centuries. In term of states using armed politics in war, the most obvious 20th-century example is the Tet Offensive in Vietnam in 1968, which attempted to send a direct political message to the US public to give up the fight.

The link between armed politics – the blurring of lines between military and political action – has historically given rise to conflicts that occupy a grey zone between war and peace, as it does today. Think, for example, of the long periods of the 19th and 20th centuries during which Britain considered itself to be at peace. It nonetheless regularly engaged in gun-boat diplomacy or punitive campaigns to coerce local leaders: this would not have seemed like peace for those on the receiving end of actual or threatened imperial power.

Or take, for example, the British attempt to keep in check the Pathan (now known as Pashtun) tribes on India's North-West Frontier with Afghanistan. There was hardly a single year between 1849 and 1947 without one or more military campaigns in the region. Each campaign was intended to reach some kind of political settlement with the various tribes; force was used with an admixture of money and threats to maintain a delicate political balance for almost a century.

This was armed politics, and the outcome was defined in terms of an ongoing attempt to achieve political stability, not in terms of the defeat of an enemy and the end of a war. While successful in a sense of continuously managing the problem, the long-term fusion of military and political activity had destabilising consequences: this century-long grey zone between war and peace ultimately encouraged Islamic fundamentalism to take root in the region, and never dealt with the root causes of the problem.

The difference with the present is that during the century the British Indian Army manned its outposts on the North-West Frontier, the world was less interconnected, both in terms of individuals and states, so an ongoing conflict of armed politics on India's North-West Frontier was a regional, not an international issue.

IV

The comparison of the North-West frontier to the war on terror brings into relief the fundamental catalysing role of the information revolution in one final area, which is the way contemporary globalisation, by linking international to local issues, blurs the idea of peacetime action in a criminal jurisdiction on the one hand, and wartime action against an enemy in war on the other.

The idea of the criminal enemy expands the scope of conflict because it's an open concept. Anyone can be an enemy by committing a proscribed act. That enemy identity is hard to lose, because criminal status endures until punishment or amnesty.

Is someone who "likes" an al-Qaida post on Facebook the enemy, or someone who once fought for al-Qaida but is now passive still the enemy – who knows? That ambiguity, and the consequent ambiguity about the collection of information and potential targeting of that individual is what blurs the line between war and peace, by expanding the scope of who the enemy might be.

Ultimately it also expands the scope of the conflict.

The developing tension over industrial cyber espionage between China and the US reveals the vexed relationship between criminal identity and the boundaries of a wider conflict. Is the US Department of Justice's criminal indictment of Chinese military officers really aimed only at them or, more likely, at the Chinese state? The US move is likely deliberately ambiguous. China will likely retaliate through coercive communication of its own, such as economic pressure Beijing can leverage over Washington. So is this a conflict or not, and if so, what are its boundaries that compartmentalise coercive activity from peacetime relations? That's not clear, and that's the point.

When a conflict is less about defeating a clearly -identified enemy than about using a combination of violent and nonviolent action to enforce a norm in the minds of a fragmented set of groups – whether it be not supporting al-Qaida, supporting the Iraqi government, not destabilising Ukraine, or not engaging in industrial espionage – we encounter the paradox of contemporary armed conflict: that violence outside the traditional concept of war, as armed politics, is proliferating because it's effective in a highly networked world. But armed politics breaks down the boundaries between war and peace, and so requires different ways to think about peace than simply the absence of war.

In that light, if there is a legitimate comparison to 1914, it is that, as in 1914, nobody knows if there will be another world war in the near future; bets either way are just -speculation.

We need to deal with international political violence as it is, in order to compartmentalise it and not have it contaminate international politics; that means ultimately limiting goals and having restrictive concepts of the enemy, not permissive concepts that expand conflict by treating a fragmented set of groups as single enemies, and conflating the enemy with the criminal.

Perhaps the better comparison is not 1914, but 1919, when at Versailles the Kaiser was branded a war criminal and Germany was forced to pay reparations to compensate for its "war guilt". As we all know, this was peace that led straight back to war. ?