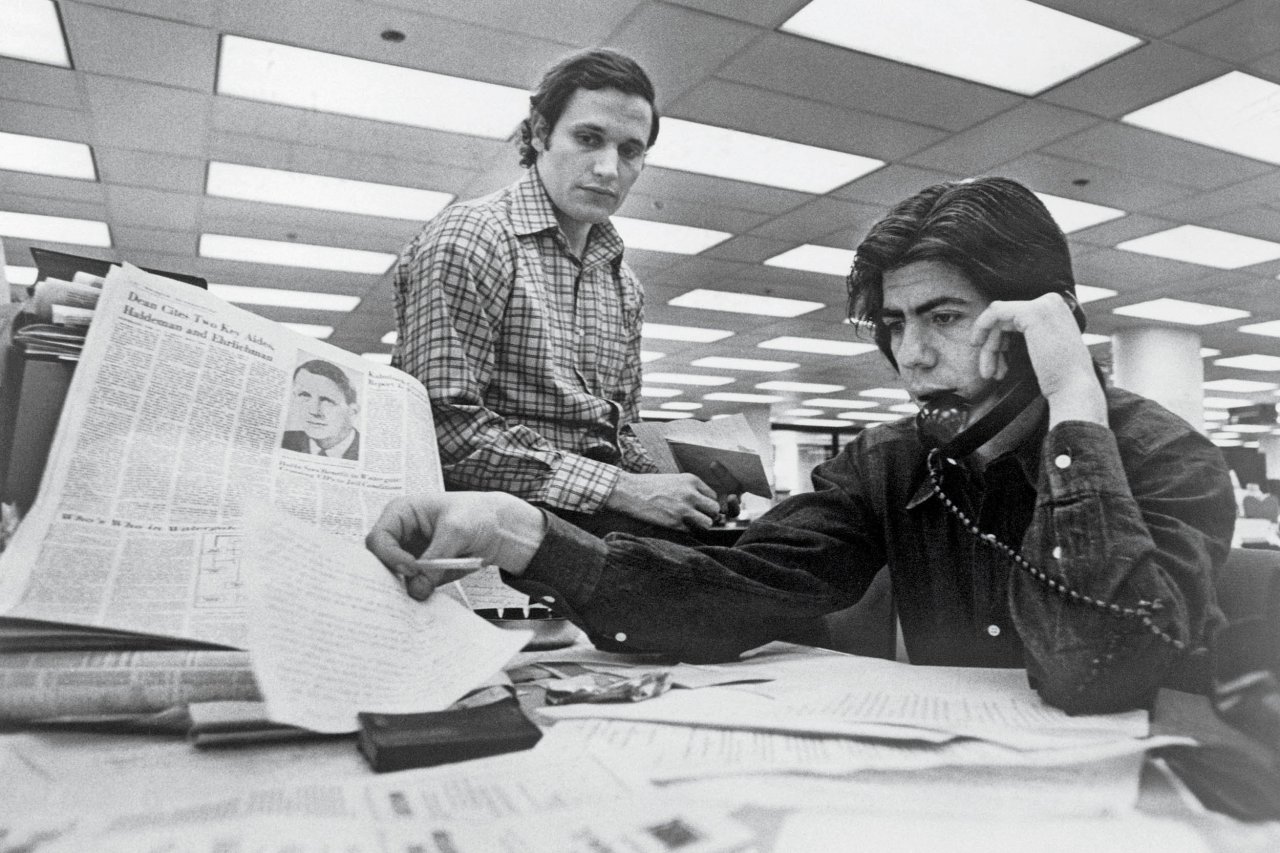

In 2005, W. Mark Felt came forward in Vanity Fair to identify himself as journalism's most famous secret source. The 91-year-old former FBI executive admitted—with a little push from his family—to being Deep Throat, the anonymous source whose information was vital to numerous scoops about the Watergate scandal written by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in 1972-73. A national guessing game that had been played for 31 years seemed over.

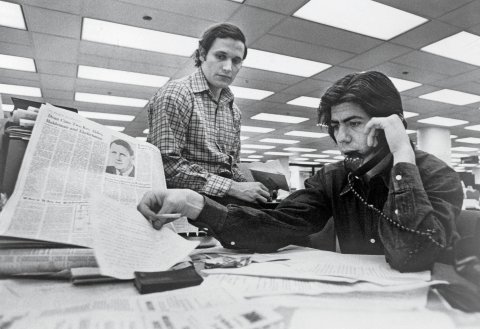

Yet the arrival of Deep Throat in the flesh created new complications, as media scholar Matt Carlson observed in 2010. A stroke-afflicted Felt was unable to speak on his own behalf; simultaneously, "Woodstein" (as the reporting duo were known internally at the Post) could no longer dictate the terms for how to think about Deep Throat. Speculation persisted, not only over how Woodward and Bernstein had used sources but also over what Carlson called "the overall accuracy of the Watergate narrative as retold by journalists," who have a vested interest in a self-glorifying version.

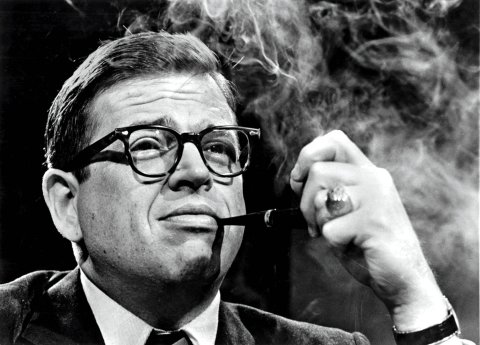

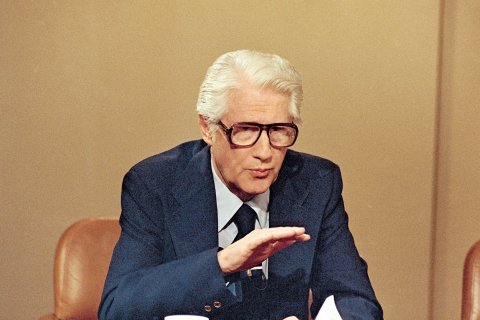

Nothing did more to stoke these doubts than a 2012 biography of Ben Bradlee, Woodward and Bernstein's fabled editor at the Post. In Yours in Truth, author Jeff Himmelman, a former Woodward disciple, described how he found an interview recorded while Bradlee was preparing his autobiography in the early 1990s. In it, the Post editor expressed doubts about Woodstein's portrayal of Deep Throat in their book on the investigation, All the President's Men.

"There's a residual fear in my soul that that isn't quite straight," Bradlee told the interviewer in 1990. Himmelman also found in Bradlee's papers a memo from Bernstein that described his clandestine encounter in December 1972 with a source identified only by the code name "Z." In All the President's Men, the information provided by "Z" was put on a par with disclosures made by Deep Throat. Himmelman put two and two together and realized "Z" was a member of the grand jury that had issued the original indictments against the Watergate burglars in September 1972—although in their book, Woodstein expressly denied getting information from anyone on the grand jury. One didn't have to be a skeptic to believe that Woodward and Bernstein were still withholding the full truth about their exploits.

Now a document has surfaced in an unlikely place that sheds sorely needed light on Woodstein's reporting while providing some perspective on the press's role in uncovering the scandal.

Oddly enough, the document—a draft of a Woodstein story from January 1973—was buried deep within the papers of Alan J. Pakula, director of the eponymous 1976 Hollywood film based on Woodstein's best-seller. Pakula, who died in 1998, deeded all his papers to the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—the people who give you the Oscars. The collection includes his copious research for All the President's Men, and in many respects, Pakula's papers are more illuminating about the book and the movie than Woodward's and Bernstein's own papers, which are housed at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas.

The 15-page draft article is an unprecedented guide to how the Post's reporting duo utilized the many anonymous sources they had painstakingly cultivated. For reasons unknown—Woodward and Bernstein have declined comment on this point—the reporters disclosed to Pakula the identities of some of these prized sources. The names are both scrawled in the corresponding margins of the draft and listed on a separate sheet of paper.

One of the six anonymous sources is the fabled Deep Throat, and he is no composite character, as skeptics have often alleged. Another is "Z," that grand juror. Three of the four others are surprises. They include one of the three original prosecutors in the Watergate burglary, a onetime lawyer for the defendants, and a Republican operative whose name is probably unknown even to those steeped in Watergate lore. Taken together and put in context, these sources reveal not only the true anatomy of a Woodstein story but also an important truth about the reporting that won The Washington Post a Pulitzer Prize in 1973.

'Is It All Going to Come Out?'

It's necessary to understand the complex backstory to this draft article before getting to Woodstein's anonymous sources and how they were employed.

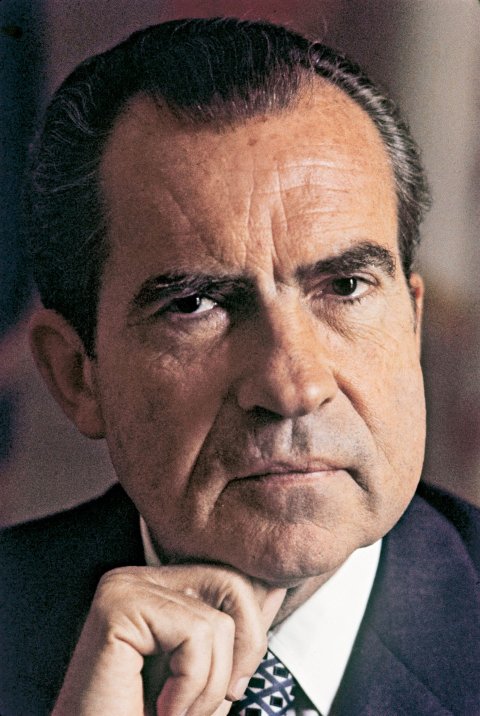

For several months following the June 17, 1972, break-in at the Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters at the Watergate office complex, all of what the late David Halberstam once called the media "powers that be" covered this unusual crime. Time, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times and the CBS Evening News all devoted significant resources to the story, though none was more dogged than The Washington Post. Still, the press wasn't having any more success than the FBI and federal prosecutors were in proving that someone higher up than the seven men indicted for the break-in were implicated in the crime, even though three of them (E. Howard Hunt, G. Gordon Liddy and James McCord) had worked directly for the Nixon administration or its campaign apparatus.

Even for Americans inclined to take the crime seriously—and many dismissed it as an election-year shenanigan—the break-in seemed to make no sense. Why would the White House sanction illegal intelligence gathering when Nixon enjoyed such a commanding lead in the polls? In any event, the caper (it was not yet a scandal) was having no effect on the election.

Following Nixon's landslide victory in November, media coverage dwindled to a dribble, including at the Post. Reporters still interested in the story anticipated the next break would come during the trial of the seven conspirators, scheduled to begin January 8. If there wasn't dramatic testimony or a breakthrough in Judge John J. Sirica's courtroom, interest in the story as news seemed likely to peter out entirely.

Midway through the 16-day trial, it became clear that nary a glimmer of new information was going to come out. Five of the defendants (Hunt and four Miamians of Cuban extraction) pleaded guilty at the outset, and not mounting a defense meant they didn't have to offer an explanation. Meanwhile, McCord and Liddy, who chose to stand trial, were uncommunicative after declaring their innocence—a plea that was especially perplexing in McCord's case, since he had been among those caught red-handed inside the DNC.

There was every reason to believe the most serious questions—chief among them: who ordered the break-in and why?—would never be answered. In the midst of the trial, Post Publisher Katharine Graham invited Woodward to lunch, an encounter described in great detail in All the President's Men because it was her first meeting with one of the reporters who was pushing her newspaper out on a limb. In a voice that barely masked her apprehension, she asked Woodward, "Is it all going to come out? I mean, are we ever going to know about all of this?" Woodward had to admit he and Bernstein weren't sure if the Watergate mystery would ever be cleared up.

On January 24, the day after Woodward heard Jeb Magruder testify in court—the only high Nixon campaign official to do so—the Post reporter signaled Deep Throat that it was time for their first substantive meeting since late October. Already in despair over how little the trial would yield, Woodstein had decided to write a story that would push the envelope, name names and get into print what was not being said in court—namely, that culpable Nixon campaign/administration higher-ups were getting off scot-free.

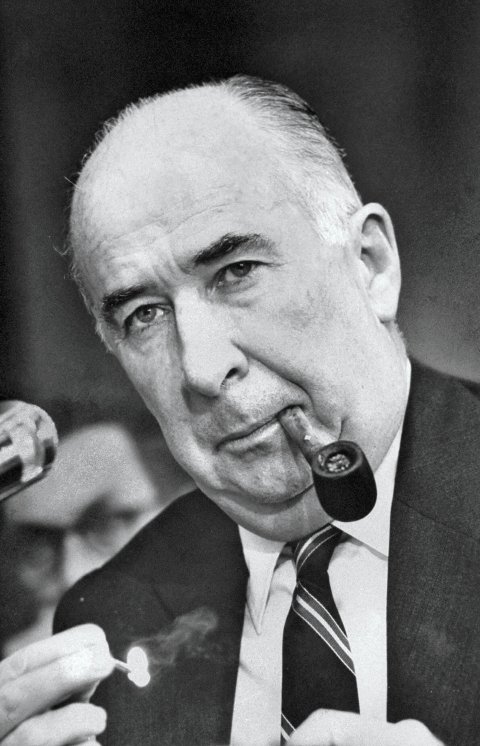

According to the account in All the President's Men, the meeting that evening with Felt was unusually frustrating. Despite the travesty of justice apparent in Sirica's courtroom, Deep Throat seemed cavalier and was infuriatingly vague, taking the position once again that he would respond only to new information and not proffer any. Woodward steered the conversation to former attorney general John Mitchell and White House aide Charles Colson, two higher-ups who had escaped prosecution and names Woodstein intended to name in the lede paragraph of their prospective article.

Felt, according to Woodward's typed-up notes, said that "there [was] not anything he would even consider circumstantial evidence to show that Colson and Mitchell [were] involved. However, it [was] the feeling of FBI heads and [Director L. Patrick] Gray that Colson and Mitchell were behind the operation—especially Colson, whose role was active. Mitchell's position was more 'amoral,'" Felt said, consisting of "giving the nod but not conceiving the scheme." If the FBI could not prove this "investigative assumption," Deep Throat later opined, he didn't think the Post could either.

Desperate not to leave the garage empty-handed, Woodward outlined the prospective story about Mitchell and Colson and bluntly asked Felt if he thought the Post had gathered enough for an article. That was for the newspaper to decide, Deep Throat responded, but Woodward noticed that Felt "didn't seem impressed with the story."

After conferring with Bernstein—at the time, the only other person who knew Deep Throat's identity and the extremely sensitive position he held—Woodward forged ahead, ignoring Felt's tepid reaction. Bernstein then reworked the draft three times. The lede graph was taken directly from Woodward's garage rendezvous with Felt on January 24:

Federal investigators concluded that former Attorney General John N. Mitchell and Charles W. Colson, special counsel to the president, both had direct knowledge of the overall political espionage operation conducted by the men indicted in the Watergate case, according to reliable sources.

The most critical "reliable source" in this rendering was Deep Throat, but Woodstein also wove in quotes from five other confidential, unnamed sources in the reporters' effort to produce a persuasive account of Mitchell's and Colson's roles.

The first anonymous source (other than Felt) mentioned in the draft is someone "whose name appeared on the witness list" for the ongoing trial. This person is quoted as saying that E. Howard Hunt told him that "typed reports [from the bugging] were going to Mitchell" and that Colson had approved the break-in "because he is an operator and realized these things are necessary."

This anonymous source, according to the guidance given Pakula, was Robert F. Bennett, then the owner of the Robert R. Mullen Co., an elite public relations firm in Washington. Hunt had worked at Mullen part time while also working as one of the White House "plumbers," the jocular name given to a secret unit that investigated leaks of classified information.

That Bennett (who later became a U.S. senator from Utah) was a Woodstein secret source has long been known. The much lesser-known House hearings on Watergate located a 1973 CIA memo disclosing that Bennett "has been feeding stories to Bob Woodward of The Washington Post with the understanding that there be no attribution to Bennett. Woodward is suitably grateful for the fine stories and by-lines which he gets and protects Bennett (and the Mullen Company)."

A second anonymous source, described as someone "who knows the four Miami defendants," is then quoted in the draft article to substantiate the point that Hunt told the defendants of Cuban extraction that the bugging operation "was for Mitchell" and that "Hunt [had] reported to Colson."

This source was identified in the margin as "Roth," a.k.a. Henry B. Rothblatt, who initially represented the four Miami-based defendants arrested at the DNC's Watergate headquarters.

In retrospect, Rothblatt's cooperation with Woodstein was not that surprising, as defense lawyers often try to make their case in the court of public opinion. But, more significant, by this time Rothblatt was the former lawyer for the Miami-based defendants. They had dismissed him weeks before, on the grounds that he refused to change their pleas to guilty. Rothblatt, who died in 1985, would later contend that the four men had been induced to change their pleas, and he eventually served as a prosecution witness during the trial of those indicted for the Watergate cover-up.

The next anonymous source cited in the draft—described as someone "familiar with the federal investigation"—is quoted as saying that Mitchell and Colson "got information about what was received" from the wiretapped conversations.

Woodstein revealed that this source was "EE," initials that stood for Elayne Edlund, the member of the Watergate grand jury who had been interviewed secretly by Bernstein in December.

Edlund's identity was supposed to be as closely guarded as Felt's. That's because grand jurors take an oath to keep secret the testimony given before them and their deliberations. As noted earlier, in All the President's Men Woodstein deliberately obfuscated the fact that "Z" was a grand juror, pretending she was a conventional source while asserting they had received "no information" from any grand jurors. Her true role became known only in 2012, when Jeff Himmelman found the memo of Bernstein's interview with her in Bradlee's papers. Even then, Himmelman shied away from naming Edlund, not knowing that she had died in 1991.

At this point in the draft, Woodstein turned to Deep Throat again—described as someone "who is familiar with the FBI investigation"—to reiterate their lede: namely, that "information in FBI files shows that 'Mitchell was involved and knew'" about the break-in, but that there was still a "substantial debate" within the bureau about Mitchell's involvement and "whether he had done anything illegal."

Felt/Deep Throat was identified as "Bob's Guy" (on the separate sheet of paper) or "Friend" (in the margin) for Pakula. Thus, Felt was the only source whose true identity was kept secret from the movie director.

The fourth anonymous source utilized is described in the draft as "one of the handful of people fully knowledgeable with the facts in the case." This source is cited as saying that "much of the federal investigation concentrated on Colson," widely reputed to be Nixon's political hatchet man, and that if an eighth defendant had been indicted, "that person would have been Colson."

This source, identified in the margin as "Glan" and on the separate sheet as "Glanzer," was, of course, Seymour Glanzer, one of the three U.S. attorneys prosecuting the seven original Watergate defendants.

Prosecutors are notorious for trying their cases in the press before or after trying them in court. But until now, it had not been known (though some suspected) that one of the Watergate prosecutors was apparently leaking to Woodstein. Glanzer, a colleague says, would vehemently deny making such statements to the Post duo, and there are ample grounds to believe that they stretched his words.

The last anonymous source Woodstein deployed has never been tied to the reporters. Even to persons steeped in Watergate minutiae, his role as a Woodstein source will come as a surprise. He is described in the draft as "one official at the White House who asked not to be named," and was cited to support the contention that "it was generally understood in the Executive Mansion that Hunt was working on secret projects for Colson dealing with the president's re-election."

The name "Fleming" is scribbled in the margin, and "Flemming" is listed on the separate sheet of paper. According to former White House counsel John Dean, that means he was Harry S. Flemming. His father, Arthur S. Flemming, was a well-known educator and civil servant who served as Dwight Eisenhower's secretary of health, education and welfare from 1958 to 1961. But Harry's profile was much lower. During Nixon's 1968 campaign, he was the liaison between the campaign and the Republican National Committee. After the election, he joined the White House staff as a special assistant for presidential personnel, leaving two years later. During the 1972 campaign, Flemming, who died in 2003, worked part time on the campaign and knew many of the key Watergate actors. Yet, as a second-tier official, he was barred from meetings when subjects like "electronic surveillance" were discussed, and his knowledge was generally secondhand.

The Biggest Scandal

Why was Pakula, known in Hollywood as a perfectionist who researched his films deeply, so intrigued by this one article, out of the dozens written by Woodstein during the fall and winter of 1972-73? Why did Woodstein not only show the director the raw draft but share the identities of all but one of their confidential sources? Ironically, all this came to pass because the draft article was never published in the Post.

As recounted in All the President's Men, the draft "produced the most serious disagreement between Bernstein and Woodward since they had begun working together seven months earlier." No matter how many times Bernstein ran the story through his typewriter, Woodward expressed reservations, saying "he didn't think it should run until they had better proof."

Woodward's doubts probably stemmed from Deep Throat's tepid reaction, and his comment that the Post was unlikely to succeed where the FBI had failed. Then, too, just two or three Watergate stories ago Woodstein had made a damaging mistake in a story about White House Chief of Staff H.R. "Bob" Haldeman. The White House had pounced on that error, and the shadow it cast over Woodstein's reporting left the duo thinking they might even have to resign from the newspaper.

Bernstein had no reservations, arguing that the Post didn't have to offer definitive evidence. The story was what investigators "thought," not what hard evidence showed, and on that basis the draft merited publication. The argument between the two reporters became so heated that on more than one occasion they retreated from the newsroom to the vending-machine area so they could shout at each other.

Their partnership—what J. Anthony Lukas later termed "a kind of journalistic centaur with an aristocratic Republican head and runty Jewish hindquarters"—never seemed closer to being ruptured. Bernstein accused Woodward of playing into the White House's hands, while Woodward accused Bernstein of trying to push a story into the paper that might lead to another, even more damaging attack on the Post by Nixon Press Secretary Ron Ziegler. Woodward did not want to reprise that episode, especially after his talk with Katharine Graham over lunch.

Pakula was making a "buddy" film—the odd-couple nature of Woodstein was what had prompted actor Robert Redford to buy the screen rights—and the Hollywood director undoubtedly wanted to know why they had argued so bitterly in late January 1973. In retrospect, Watergate was on the verge of metastasizing into the biggest presidential scandal since Teapot Dome and, soon, the first effort to impeach a president in 100 years. So the Post reporters gave Pakula the kind of access normally reserved for newspaper editors only.

After Newsweek showed them a copy of the draft article, Woodward and Bernstein acknowledged that it was "obviously authentic." But they said they didn't know how Pakula got hold of their never-published draft, and why (or if) he had been particularly interested in it.

They would not discuss the disclosure of their sources' true identities, partly because the handwriting in the margins of the draft article was not clearly legible and used abbreviations—i.e., "Ben" (for Robert F. Bennett) and "EE" (for Elayne Edlund). "Because it is not clear whose handwriting is in the margins (not necessarily ours) and the story may involve sources who are still alive," Woodstein wrote in an email, "we just can't comment."

It matters not one whit, of course, who scribbled the identities in the margins. There were only two people who could have revealed that information: one of them is Woodward, and the other Bernstein. They probably had little difficulty remembering who the abbreviations refer to, since they also told Newsweek that the draft story "shows once again that we had multiple sources for our work on Watergate, in and out of government, from many different institutions, individuals, and vantage points."

Besides this peek at how Woodstein constructed a Watergate story, the draft conveys an important historical truth that is frequently forgotten. The Watergate scandal, which played out over 26 months from beginning (the break-in) to end (Nixon's resignation in August 1974), was an extraordinarily complex saga. Yet because of All the President's Men and especially its film adaptation, the story is too often reduced to a convenient and appealing fable, the tale of two young and hungry reporters who brought down a president, wielding truth as their only weapon. Or, as the critic Wilfrid Sheed put it, "folks may be getting fuzzy about the Watergate details, but at least they remember the movie: a couple of nosy journalists and an informer, wasn't it?"

The draft explodes this myth. The document in Pakula's papers, together with the backstory, demonstrates that seven months after the Watergate burglars were caught, the press was in a position akin to the blind men and the elephant parable: still struggling to understand what it had its hands on. Woodward and Bernstein were no closer to revealing who approved the break-in than they had been in June, and even further away from exposing the obstruction of justice that followed the break-in. And it was the cover-up, after all, that ensnared Nixon and put in motion the ultimate political sanction of impeachment.

If there are more accolades to be awarded for cracking the case, they belong to the legal system, in particular, the three prosecutors—the aforementioned Glanzer, Earl J. Silbert and Donald E. Campbell—who inexorably closed the legal pincers until one of the original Watergate defendants, James McCord, finally broke ranks not long after his January 30 conviction. McCord's March 23 letter to Judge Sirica claiming that perjury, among other crimes, had occurred during the trial was a devastating blow from which the administration never recovered. Soon, everyone involved in the cover-up began to lawyer up—most significant, John W. Dean, the White House legal counsel—and the race to confess to prosecutors began.

The media, and most prominently Woodstein, deserve enormous credit for keeping the story alive, especially prior to the 1972 election, when the break-in was regarded with a combination of apathy and nonchalance. The dissonance between the suggestive stories in the press and the White House's dismissive "non-denial denials" before the election created an enormous credibility gap. Press coverage served as a prophylactic for prosecutors, allowing them to proceed steadily and without interference, in keeping with the legal adage that the "wheels of justice turn slowly, but they grind exceedingly fine." Ultimately, it was the work of the Watergate grand jury and these prosecutors—not the press—that produced a road map to all the criminal cases by the time a special prosecutor was appointed in May 1973.

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were only two of many actors in the Watergate drama, and perhaps not even the most important ones, notwithstanding Redford's extended effort at idolatry. (Last year he produced another Watergate film, this time a documentary, All the President's Men Revisited, which was really All the President's Men Repeated, as Yale historian Beverly Gage observed on Slate.)

Watergate will always stand as one of the news media's finer hours. But as the draft in Pakula's papers shows, even with all the anonymous sources Woodstein developed, credit for justice being served must be shared with the legal and congressional processes. The era of worshipping the reporting of Woodward and Bernstein should be brought to a merciful, and decisive, end.

A footnote: "Woodward now agrees that the story should have run," Bernstein and Woodward said in their response after seeing the draft article. Had that been the case, though, The Washington Post would have been sorely embarrassed. In its January 29 issue, Time magazine published virtually the same allegation about Mitchell and Colson—hardly surprising, since Mark Felt was also leaking like a sieve to Time's Sandy Smith. After Colson threatened to file a multimillion-dollar libel suit, however, Time quickly apologized and retracted the story. Colson did a lot of things, including participate in the cover-up. But there was never any proof he approved the break-in beforehand.

As for why Mark Felt was so indifferent about spreading bad information around, i.e., making Colson the principal higher-up rather than Mitchell…that is another story.