It is midnight during Ramadan and my two elderly aunts are preparing a meal, their evening disrupted by a stream of relatives coming to see me, my husband and two daughters. I had come to Germany from the United States to be reunited with a family I had not seen for two decades – 14 aunts and uncles and 60 near and distant cousins, the older generation part of the diaspora of six million people that fled Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion.

With around 130,000 other Afghans, they settled here in the early Eighties, keen to maintain a bourgeois lifestyle and educate their children away from an oppressive regime. Yet here in her tidy Hamburg apartment, tensions are evident, newspaper headlines reflecting concerns about the spread of Islamic State and the young Germans who wanted to join them.

It has proved impossible for my relatives to completely escape the tentacles of radicalism, then or now. Though most of the children born to those who fled have thrived in the workplace and professions, one of my distant relatives was jailed in 2011 for fundraising and recruiting al-Qaida members in Berlin; another killed in Syria this year, and the wider family constantly argue about the various shades of mystic Islam the older generation cling to versus the radical Islam of younger members.

On this July night, my paternal aunt Nazanin prepares green tea and sets out nuts and sweets on the coffee table. The doorbell rings and I open the door to my 45-year-old cousin Ali and his 35-year-old wife Aisha. She is wearing a black headscarf and a long abaya. I hold out my hand to Ali but quickly realise shaking a woman's hand makes him uncomfortable. His wife kisses me on the cheeks three times – an Afghan custom.

Nazanin fixed on Aisha's clothing: "So why are you wearing this Arab headscarf? You didn't even wear a headscarf before. If you were going to take on the headscarf, why not wear it like her?" says Nazanin, 71, pointing to my Aunt Shamsia, 82, who wears a colourful headscarf knotted loosely, with greying strands of hair peeking out. "Isn't that modest enough? Why do our young people think that if you follow Arab culture and style, you have become true Muslims?"

Aisha, caught off guard, tries to explain. "It's modest but I think only the hands and face should show, not any hair. We must follow Islam correctly."

A healthcare worker with three children, her family had travelled to Germany from Afghanistan when she was 13. Frequent visits to Hamburg mosques had convinced her of the importance of the revival of the Caliphate, persuaded her that these elders didn't understand there was only one true Islam, its essence not open to their many interpretations.

My aunt was furious. She had heard these arguments before from her nephews, members of a generation of hundreds of young German Muslims who were turning to an Islam she regarded as rigid and intolerant. Nazanin fasted, prayed five times a day, had completed the Hajj pilgrimage, and gave more than enough alms but somehow, in the eyes of born-again Muslims like Aisha, she wasn't devout enough. She had seen younger Afghans joining banned political groups, some travelling to fight in Syria and Iraq, nearly all of them evangelists.

Their exchange was typical of conversations in homes across Europe. Afghans represent only a small proportion of radical Western Islamist recruitment but more than 450, including women and German natives, have left Germany for jihad over the past two years, says Pamela Müller-Niese, a spokeswoman for the German Interior Ministry. Since the dramatic military conquests of ISIS this summer, radicals raised the group's black flag in support on German streets.

On July 12th, the flag was flying high in central Berlin among the 800 people demonstrating against Israeli strikes in Gaza. The estimated 1,500 Salafist Islamists have been accused of committing the most violence and disruption in North Rhine Westphalia. A group of six men, including one German convert and six ethnic Chechens, were arrested after a fight broke out in a Yazidi-owned restaurant with knives and bottles on August 7th in Herford. The 31-year-old restaurant owner and a 16-year-old Yazidi boy were injured in the fight.

Lower Saxony and North Rhine Westphalia are home to an estimated 60,000 Yazidi immigrants, a religious minority ISIS has been persecuting in Iraq. A few hours after the restaurant attack in Herford some 300 Yazidis rallied against the violence but a band of hooded men clashed with them.

It took about 100 German police officers to control the mob. Then in Wuppertal, on September 3rd, 11 Salafists dressed in orange shirts imprinted with "Sharia Police" patrolled nightclubs and gambling halls telling patrons not to drink alcohol or gamble.

The leader of their group Sven Lau, a German convert to Salafi Islam, told the press he was just riling up a debate about Sharia law in Germany. The publicity stunt worked as discussions about Islamic radicalism and Sharia or Islamic law seized German airwaves.

Germany has been lucky to avoid a large-scale attack: in December, 2012, a bomb planted in a Bonn train station detonated yet failed to explode. Passengers noticed an abandoned bag holding the explosive and alerted police. Marco G (last names are not given in full because of German law), a 27-year-old German convert to Islam, was arrested and is on trial in Düsseldorf currently for the attempted bombing. He's also being charged for an alleged foiled assassination attempt against Markus Beisicht, leader of the rightwing Pro NRW party, with three other men Enea B, 44, Koray D, 25, and Tayfun S, aged 25. All four men, arrested in March 2013, are radical Salafists, according to German court records, and are facing allegations.

In response to the insecurity, German authorities are banning Islamist groups, including support for ISIS, and trying to prevent Germans from joining jihadist groups in the Middle East. Authorities are seizing passports and planning to mark German identity cards of individuals suspected of travelling to Syria or Iraq so that European border agents can stop them. The government is considering revoking German citizenship of those with dual nationalities.

"If and when there is information suggesting that Islamists intend to leave the country to take part in fighting abroad or to otherwise support jihadist endeavours, the German security authorities do all they can under German law to prevent their exit," Müller-Niese said.

About 60 German citizens have been turned back from travelling to Syria and Iraq. Kreshnik Berisha, a 20-year-old jihadist who returned from Syria, is the first German to go on trial for allegedly fighting for ISIS, now deemed a terrorist organisation. Germany, like France and the United Kingdom, is on a high security alert. The German public is clearly afraid – particularly moderate Muslims who fear a backlash and suffer overt discrimination. Five German mosques were torched in September.

The majority of the 4.5 million Muslims who live in Germany do not share extremist views and last month thousands of the apolitical members of Germany's 2,000 mosques demonstrated against radicals in seven German cities. Among the demonstrators were 50 worshippers from the Ibrahim Khalilluah Islamic Centre, the largest Afghan mosque in Hamburg. It's here that Nazanin and many of my relatives come together for Friday prayers and special events, meeting old friends and reminiscing about Afghanistan.

"We wanted to show Germans not to be afraid of us. Islam is a religion of peace. We also wanted the extremists to know that they are a minority and we will stand up to them," the mosque president Basir Azizullah tells me.

My aunts and uncles are fearful, convinced their families are under surveillance by the German police. Talking to those cousins who have become radicalised, it's clear the attractions of radical Islam vary from one individual to another. Some have suffered racist jibes at school; others are attracted to the idea of fighting a jihad because they have a sense of injustice about Western policies in the Muslim world. Many of their parents, however, suspect Western forces are behind their children's radicalisation. They believe that ISIS is a group covertly supported by Gulf Arab states and the US to kill Muslims and defame Islam in the West.

Most of my extended family escaped the unrest in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion in the early 1980s and settled abroad – the majority finding asylum in Germany. My father's younger brother Fazel Ahmed Ahrary, a university professor, was killed by the communist leadership. My parents, Fazul and Sayed Nawa, packed up their belongings and with my 16-year-old sister and I, then aged nine, walked six hours across the desert from Herat to Iran in 1982 after my school was bombed by the mujahideen. I witnessed my classmate die and later watched a stray bullet shatter our living room windows.

My father was an administrator for the National Fertiliser Company and my uncles worked in government posts in Herat and Kabul. Many of my female relatives were teachers and poets. Some of my uncles initially joined the communist movement while others sympathised with the mujahideen. But they abandoned those beliefs when the reality of bloodshed and war hit home.

None of us were around for the Taliban era in the late 1990s when women were banned from public life. More than a million Afghans died in the Soviet-Afghan war. Pragmatism replaced ideology after they migrated to the West.

"These ideologies were dictated by outside powers – Saudi Arabia, the US and the Soviet Union – in Afghanistan," says Rind, my mother's brother and an engineer in Hamburg.

"At first, I was impressed with a rigid form of Islam. I used to come home and yell at my sisters and younger brothers to pray. Then I was impressed with the force of communism. But I evolved and life experience showed me that the best way to live is to be practical and inclusive. What these young people here do not understand is that their hardcore practice of Islam is also being dictated by some of the same external powers again."

Rind, 65, and his wife Donia, 48, have lived in Germany for 32 years. All their four children, aged 7 to 27, were born here, but the couple struggle to raise them with their own values. His family's story is an example of the complex generational and religious divide rocking the families of immigrants and converts in Europe.

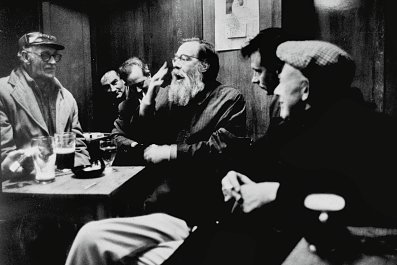

When Rind comes home, he seeks refuge in the basement he built as an artist haven for fellow Afghans. He loves to hold parties there. On one side of the wall, he painted a circle of musicians from different faiths playing their instruments and creating harmony. In the midst of their circle, my uncle inscribed a Sufi poem that encapsulates his faith.

"Religion for me is inclusive, whether it's Islam, paganism, Judaism or Hinduism. I have respect for all the religions and anyone who has a pure heart, empathy and love for music should come and join us. They have a place in my heart and home," he says.

Rind's oldest son Amin, 27, has learned to play the harmonium and sing in Farsi, our native language. Amin, a postgraduate student, flirted with Islamic conservatism when he was a teenager but as he travelled and met people with different beliefs, he found comfort in a more liberal lifestyle. Yet he understands the attraction of hardcore Islam.

"As a foreigner, you don't have respect, you're not accepted in their society, you're without a nation. There's a hole in your identity, and for some, this extreme Islam fills that hole," he says. "I still struggle with discrimination, but I don't use it as a crutch. The Islamist agenda is to use that discrimination as a tool to fuel radicalism and separate from society," Amin says.

But Rind's middle son Karim, 25, chose the strict interpretation of Islam and joined Hizb-ut-Tahrir, a political Islamist party banned in Germany but still active there. Karim considers his father's parties, where men and women mix, the women rarely wear the headscarf and some of the guests drink alcohol, to be sinful. To him, Islam is about rationality and logic.

When Karim was a teenager, he lost three friends: one committed suicide, one was hit by a motorcycle and one was hit by a car. He began to ponder existential questions like "what is the purpose of this life, where do I go after this?" Some of the answers could be found amongst discussions with Hamburg's Islamists Hizb-ut-Tahrir (HuT). He read the Koran in German, English and Arabic and, he says, found the light. "It's not because we're confused or bitter or want vengeance that we believe this. It's because it's rational. We believe in change through intellectual debate," he says, stressing that his party members are non-violent in Germany.

The party, active in 40 countries including the UK, calls for the return of the Caliphate and Islamic law in the Muslim world. It rejects democracy and Western influence. All these tenets appeal to Karim, who's active in distributing literature and informing other young people about the organisation. He's so persuasive that his friends' parents complain to Rind. "They say I brainwash their kids . . . I just tell them the truth," Karim says, smiling.

The tipping point for my uncle and aunt was Karim's triumph in convincing his younger sister Hanifa, 14, to pray and wear the headscarf secretly at school. Donia noticed the change in their daughter – her grades were falling and she was reading religious books instead of her school books. They told Karim to leave the house and got him an apartment. "We thought it would be good for him to be on his own. He might change," she says.

Since then Hanifa, who feels caught between her parents' rules and her brother's ideology, has given up the headscarf but she continues to pray and fast. She said she values God and spirituality while her German classmates don't. She's reading more about Islam so she can make her own decisions. The thoughtful teenager says her parents are so afraid that she will become like Karim that they do not even like her practicing any form of the religion.

"I'm not interested in politics and parties. They are afraid of religion altogether, and I say it's separate," she says.

Karim still visits his parents but avoids political discussion. He felt a bond with Hanifa but the eviction from his house to separate him from his sister hit him hard. "Families I know have accepted gay sons, but my family will not accept me for my beliefs," he says. Karim also feels judged and estranged from the Islamophobic German mainstream. In 2012, he was giving a speech in front of the class at the private college he was attending when a medical back belt he was wearing under his shirt came loose. The students feared Karim had explosives on him. Half of the students didn't show up to the class the next day and the school administrators called the police to interrogate Karim.

Müller-Niese of the Interior Ministry says HuT party was banned in 2003 for being intolerant toward other faiths, anti-Semitic and supporting violence to achieve political goals yet members of the party, who boast at least 2,000 German-Muslims, met openly in study circles at Hamburg's Ibrahim Khalillulah mosque and recruited members until five years ago, when the authorities asked the mosque to kick them out. The mosque is funded by donations from its members and small real estate investments. Mosque leaders agreed and now the mosque has become active instead in trying to deradicalise young Muslims but they don't appear to be having much luck.

Azizullah, a native Afghan and the mosque president, said the only way to convince radicals to leave the violent path is to call on Islamic scholars from Afghanistan who have experience in dealing with militant mentalities. He claims he has invited Afghan scholars, including Nabiullah Manawi, a cleric who preaches against radicalism inside Afghanistan, but German immigration has rejected their visas. "We do not have the expertise to keep these young people from extremism," he says. "We want these scholars to show through the Koran and Hadith how the Prophet Muhammed lived with other religions in harmony, including Jews. These young people need to learn about the tolerance of the Caliphate."

Islamist recruiters approached my cousin Karim to fight in Syria but he refused because of the infighting among Muslims.

Not all of my relatives shun violence. Uncle Rind warns Karim not to become like Maqsood Lodin, a notorious distant cousin few of us have met in person. Lodin, my maternal aunt's nephew by marriage, was convicted and sentenced to six years and nine months in prison in Berlin for fundraising and recruiting for al-Qaida in 2011. His parents declined to speak because they do not want to relive the painful moments that resulted from their son's mistakes. Lodin and his lawyer, Linke aus Karlsruhe, refused to comment.

In 2009, Lodin's parents reported him missing to the Austrian police. In the two years Lodin disappeared, he befriended Yusuf Ocak, the suspected founder of the German Taliban Mujahideen, and traveled to Waziristan, Pakistan where al-Qaida allegedly trained them to use weapons, explosives and digital encryption programming, according to German police reports.

Germans arrested Lodin in May 2011 in Berlin, where he had returned to recruit in the Muslim community and had already collected money for al Qaida. Police found a memory card and storage device containing pornography. After it was decoded, 46 pages of documents about the terrorist group's future operations were revealed.

When my relatives discuss Lodin, they are relieved that he is alive in jail and not blowing himself up in a terrorist attack. But another distant cousin's son, who grew up in Frankfurt, was allegedly killed in his quest for jihad. Friends of Hakim who were with him in Armanaz, Syria told his parents that he was killed in an attack in a house on March 4th this year.

They sent his family photos of the 22-year-old, unconscious, injured and bleeding on a shawl. These friends who were fighting against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's regime reported that Hakim was buried in Binnish, Syria, a stronghold of ISIS and where the late American journalist, James Foley, was kidnapped.

His mother Fatima was so distraught, she initially didn't believe these friends were telling the truth. "These groups try so hard to break apart families, I wouldn't be surprised if they were just lying to us to keep him away from us."

Fatima, 47, asked me to find out if her youngest child was really dead. The Syrian Tracker, an organisation that records names of those who die in the war, do not have his name on their roster but two unidentified men killed from gunshot wounds in the Idlib region on March 4th are listed. I wonder if either were Hakim. But finally, it's Hakim's father Tarek who confirms that his younger son has been "martyred". His wife is simply in denial.

Hakim was a member of a unit of 120 young men from Germany who do not align themselves with any specific group in the Middle East, Tarek says. Their goal is to fight against the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad and that day in Armanaz, they had raided a house with government officials when a tank was fired at the house and Hakim was fatally hit.

His mother can't stop thinking about Hakim and what went wrong. Tarek fought as a mujahideen against the Soviets. Even when they immigrated to Germany in 1994, Fatima kept her headscarf on and encouraged her children to learn about Islam. But she insists that their religious teachings encouraged acceptance, not violence. She said the biggest mistake they made was to move from a small village in southern Germany to Frankfurt where many uneducated, broken Muslim families with "oqda", a bitterness that leads to need for vengeance, lived. The children of those families became her son's friends.

She doesn't cry but she wonders if her empathetic son was saddened and driven away by the excessive materialism and immoralities he saw in Germany, or was he just brainwashed by his peers in the mosque?

She knows he was bitter and angry at the videos he watched online showing the atrocities of the Syrian government against rebels and civilians. "He insisted we couldn't live comfortably and ignore the injustice. He said this is true jihad and it's mandatory for Muslims. I tried to stop him."

At first, she was happy that Hakim, a political science student at university in Frankfurt , was going to a local mosque to pray, but in just four months, he changed dramatically. Like Lodin, Hakim altered his style of clothes, joined a group of radicals and went to the mosque for every prayer. The mother asked the mosque's imam to talk about these changes. But Hakim quickly changed mosques and worked to raise money for his trip. With his German passport and mobile phone, he flew to Turkey. His parents contacted him on his mobile, then they reported their son's departure to the German police.

Fatima said the Islamic State had not emerged as a terrorist group yet and German police told them they could not bring back their son. Tarek flew to Turkey and met his son in Antakya on the Turkish-Syrian border. They spent the weekend together. "He was reading his religious books and said little about what he was doing in Syria. He just told me that he and his group of friends were helping victims of the war," Tarek says. "He said he was happy and didn't want to spend another second in Europe."

The father, a taxi driver, failed to convince his son to come home so he returned to Frankfurt while Hakim headed back to Syria. Less than a month later, his parents heard Hakim was dead through a text message sent to their older son Daud by one of his comrades. The entire journey had lasted 25 days.

At his memorial service, Hakim's friends showed up to console his family but they pulled Daud aside and persuaded him to replace Hakim in Syria. His mother was mortified when her now only son wanted to leave. She pleaded with him. "I told him that if you go, I will no longer be your mother. It's Muslims killing Muslims. Pretend you're killing me, that I'm one of them," she says.

When Fatima handed Daud the phone to talk to me, the 25-year-old said he will not fight in Syria because ISIS is a Western-supported group working against Islam. Then he paused and changed his tone: "My brother did the right thing. I support his martyrdom. You can't pick and choose what you want to follow in Islam. When Muslims are being killed unjustly, we have to stand by them. No need to cry and make a scene because he's in a better place than us."

I live among 60,000 Afghans in California who aren't as polarised or politicised as European Muslims but I see the schisms even here. Young men and women refusing to allow music and mixed genders at their weddings, rumours of men who have travelled to Yemen for jihadi training and the evangelism inherent to born-again Muslims who have found themselves and feel compelled to convert others.

My husband and I are careful to teach our daughters, aged three and six, about the pitfalls of extremism. We hope they will learn to love God and appreciate different religions and cultures, that they will not turn back the clock to live in a Caliphate but rather be part of a community that envisions a future of pluralism.

Some of the names and details have been changed to protect identities.