Nobody should have been surprised when, on January 7, 1972, the poet John Berryman killed himself by jumping off the Washington Avenue Bridge, which spans the Mississippi River where it winds between Minneapolis and St. Paul. Self-slaughter is known to lurk in the genes; those with parents who killed themselves are more likely to attempt the same act. Like that other moody and bearded Midwesterner, Ernest Hemingway, Berryman had a father who took his own life. Hemingway père used a .32-caliber pistol from the Civil War; in the case of Berryman's father, the instrument of death was a shotgun, outside the 12-year-old's bedroom window.

Berryman's poetry touched upon that gruesome deed, while musing upon his own demise with such regularity that, after a while, it came to seem like an obsession he'd stopped trying to shake. "Death is a box," he wrote in one of the nearly 400 Dream Songs that, together, make up one of the most audacious (and intimidating) achievements in 20th century American poetry. Yes, Berryman means the pine confines that await all mortal flesh, but even a grade-schooler knows of that dread finale. More stifling, for him, is the psychic trap into which he fell after his father's death. Thoughts of oblivion, unlike oblivion itself, you actually have to endure. The early deaths of fellow poets—Sylvia Plath, Dylan Thomas, Randall Jarrell and Delmore Schwartz—from suicide or drink (or suicide by drink) made sure he stayed there, and neither the Pulitzer Prize (1965) nor unrivaled fame could coax him back into the light. Like a bat, his poetry yearned for darkness. He wrote in Dream Song #120: "I totter to the lip of the cliff."

Late this October, publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux will mark the centenary of Berryman's birth (October 25, 1914) by releasing a new edition of his selected poems, The Heart Is Strange, which includes a few works that haven't been published before, juvenilia from The Dispossessed (1948)—laden with debts to Auden, Yeats and Hopkins—and late stuff from Love & Fame (1970) and Delusions, Etc. (1972), which is blinding in its pathos, biblical in its despair: "I'm loose, at a loss." Also in The Heart Is Strange is the strange and difficult Homage to Mistress Bradstreet, the 1956 poem that the eminent critic Edmund Wilson deemed "the most distinguished long poem by an American since The Waste Land." At the same time, FSG is republishing the original 77 Dream Songs, the full Dream Songs and Berryman's Sonnets, written for Chris, a grad student's wife with whom he'd conducted an affair in 1947 (he withheld publishing the amorous poems for two decades, by which time his reputation as a lothario was beyond dispute). The publisher is also releasing the memoir Poets in Their Youth, by Eileen Simpson, who had once been married to Berryman.

The reissue of a writer's work on the anniversary of his or her birth or death is nothing more than a ploy. Sometimes, the ploy is odious. Here, it is necessary. Berryman has not been forgotten, but his gnomic revelations have less force than they used to. His drinking and womanizing, his unsoothable anguish, seem less the stuff of heroism than of mutinous neurotransmitters. I can all too easily imagine him today, sitting at a seminar table in Palo Alto or Iowa City, buoyed by a decent dose of Wellbutrin, listening as some regular contributor to the Northwestern Maine Quarterly Review piously instructs impious John to simmer down, center himself, drop the unceasing allusions to Shakespeare, find his voice and tell us how he really feels. And some of the jokes are a little silly, if we are going to be honest with each other in this space.

There is also the inescapable matter of poetry's declining relevance to a nation whose finest minds devote themselves to the question of whether one should recline airplane seats. "The larger public thinks of Walt Whitman as a shopping mall on Long Island," says Philip Levine, the former U.S. Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner, who studied with Berryman more than six decades ago. Berryman's cerebral irreverence is easy enough to enjoy without a doctorate in comparative literature, but you do have to be willing to devote more time than you would to a Snapchat message.

Very few are bold enough to try a feat similar to Berryman's today, and even fewer have actually succeeded in writing poetry that transcends the artless solipsism of workshop verse. In that rarefied latter category belong Patricia Lockwood and Michael Robbins, both of whom are young and profane and unafraid. Their forefather is Berryman, who in Mistress Bradstreet writes from the voice of a 17th century poetess; who in the Dream Songs lapses (too often, for my taste) into minstrelsy; who knows that if you're not writing about longing and dying, you might as well be composing infomercial jingles.

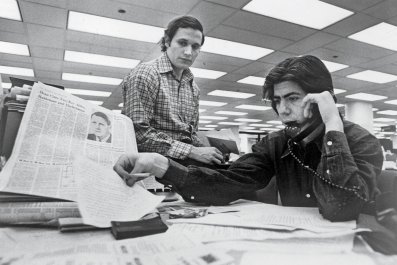

Berryman "seems pretty suited to the world right now" thinks David Orr, poetry columnist for The New York Times Sunday Book Review. It is a poetry of anxiety and attention deficit, as earnest as an episode of Glee, as revealingly scattered as the tabs left open on your browser. It is also surprisingly political for a poet who effortlessly channels Sir Thomas Wyatt's lyrical seductions, a poet who often seemed lost in the dim labyrinths of his own mind. Berryman was weirdly attuned to the chaos of the Cold War. In an essay called "Mine Own Berryman," published in the autobiographical essay collection The Bread of Time, Levine calls Berryman an "addicted reader of The New York Times," one who was particularly dismayed by the Communist witch hunts of that era. Once, in the midst of class (a graduate seminar at the Iowa Writers' Workshop), Berryman called Senator Joe McCarthy a "habitual liar," using one of the demagogue's statements as a lesson on the unruliness of language.

In "Dream Song #162," called Vietnam, he writes of a "war which was no war," confiding, frustrated, "Better would be a definite war with the dragon." Much as Auden had before him, Berryman understood how the fears of the day permeated the psyche. Here he is, for example, in "Dream Song #51":

—Are you radioactive, pal? —Pal, radioactive.

—Has you the night sweats & the day sweats, pal?

—Pal, I do.

—Did your gal leave you? —What do you think, pal?

—Is that thing on the front of your head what it seems to be, pal?

—Yes, pal.

Berryman "sounds completely like himself and nobody else," says Helen Vendler, the Harvard professor widely regarded as our foremost scholar of 20th century verse. She describes the sound of his poetry as "hesitation and jump." It can, indeed, be as furious as Charlie Parker bebop, full of what Berryman himself called "sad wild riffs." This is most evident in the first collection of Dream Songs, which please the ear even as they confound the cerebral cortex. Vendler thinks young readers might especially be enticed by the manic energy of the Dream Songs—perhaps the way they are by the same quality in, say, On the Road. "All you have to do with the Dream Songs is read them aloud to students," Vendler told me. "I think kids would love to read Berryman. He is so disreputable and rebellious, which is what they would like to be."

Fame came late to Berryman. He had wanted it badly, quickly. "I overestimated myself, as it turned out," he told The Paris Review in 1970, "and felt bitter, bitterly neglected." But fame could not save him when it finally arrived, first with Mistress Bradstreet and then, in spades, with the Dream Songs. He went to rehab. He found God. None of it worked. He wrote about trying to get sober in a late novel—his only effort at fiction, as far as I know—called Recovery, a painfully straightforward account of the drying out of one Alan Severance, who is even more obviously Berryman than is Henry, the protagonist of the Dream Songs. "I am at the point of death—physical mental spiritual," Severance says. "Highly promising. I have nothing to lose."

The late poems have a similar frankness, shorn of the madcap wit and mordant humor that mark Berryman at his best. Janis Joplin was wrong: Freedom's not the thing you're left with when you have nothing left to lose. These poems remind us less of unrestrained Parker than of the plangent, controlled Miles Davis of Kind of Blue (the more common comparison is of Berryman to Dylan, but jazz is more apt). Berryman has come to the end, and he knows it. A poem called "Damned" leaves almost too little to the imagination, and though Berryman disliked being grouped with the confessional school of poetry, it is hard to see the below as anything else:

I am busy tired mad & lonely old

O this has been a long long night of wrest.

You may hear, here, Shakespeare, Hopkins, Ecclesiastes. Or maybe just a man in Minneapolis who has lingered too often on Mississippi bridges. The only shade of the Berryman of old is the wrest/rest joke. The shade is faint. Daniel Swift, in his introduction to The Heart Is Strange, writes that in his post-Dream Songs work, Berryman "embraced the end."

Literary reputations are always rising and falling. Berryman's, once so high, has probably dipped below that of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, according to Times columnist Orr. "He's got a lot of bad work," Orr explains. "He's an erratic poet." His lapse into the demotic language of minstrelsy in the Dream Songs may turn off readers who have every right to be offended by lines like "yo legal & yo good. Is you feel well?" ("Dream Song #2") Some may want to pretend that the minstrelsy isn't there—as many have done with Henry Miller's contempt for women and T.S. Eliot's revulsion toward Jews—but current U.S. Poet Laureate Charles Wright says it remains a problematic aspect of Berryman's work and "undercuts his legacy a little bit."

Yet there is hope for Berryman. By the 1940s, William Faulkner had slipped into obscurity, to be rescued by the 1946 publication of Malcolm Cowley's Portable Faulkner, which made the case for the taciturn Southerner's immortality. It is not realistic to expect the same for Berryman in this Age of Bieber, yet perhaps the republication of his work will ignite interest among young people who long for more from the world than what flits across their screens. Paradoxically, the best of Berryman is so tangled and thorny with allusion, you can't understand the brunt of it and are thus allowed to enjoy the sound of the words, without worrying about any of the desiccated tropes that once made English class such a dreaded enterprise. To wit, the famous third stanza to "Dream Song #14" ("Life, friends, is boring"; you won't regret spending six minutes on a YouTube video of an obviously drunk Berryman getting to, and through, the poem):

And the tranquil hills, & gin, look like a drag

and somehow a dog

has taken itself & its tail considerably away

into mountains or sea or sky, leaving

behind: me, wag.

I have no idea what that means, but say the words and they simply feel right, the way a toddler's nonsensical babbling sometimes does. You could probably write a dissertation about "tranquil hills, & gin," or about the brilliantly insane syntax/diction of the last line. Reading Berryman is a reminder that poetry is sound, that it should be enjoyed as music, not words alone.

The British critic Al Alvarez once noted that Berryman had "a gift for grief." It was a gift that could morph into mordant humor, melancholy insight, unexpected piety or (at its least compelling) stifling self-pity. In the end, it was a gift on the order of the Trojan Horse, a psychic cancer that ravaged all his inner resources. He burned brilliantly, but all fires end in ashes. His tragic biography is so captivating that it threatens to upend the poetry. The best thing one can do for Berryman today is to forget him and to remember his poems.

Wright, the current Poet Laureate, says Berryman was the greatest of the midcentury poets, along with Theodore Roethke (who died at 55 in 1963, after a heart attack probably caused by drinking). Better than Bishop or Lowell, whose fame he coveted most of all. There is more in Berryman's work. Too much, sometimes. The cup runneth over. But even then...

"I hear brilliance," Wright says of the Dream Songs. "I hear everything."