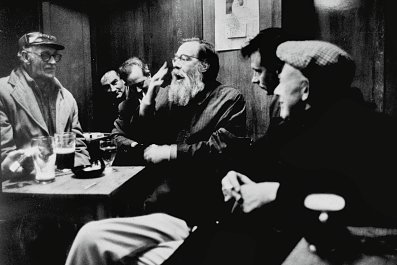

For many years, a 200-word instruction set, best known for its twelve-step programme, has held a virtual monopoly on the treatment of alcoholism. But many drinkers want to keep drinking – without all the problems.

Wim van den Brink wants to help and he believes the prevailing view is wrong. "There's only one way: that's total abstinence for the rest of your life," the spirited Dutch psychiatrist with a flop of white hair and glasses, told an audience recently. "People look for total abstinence. But it's heroic and dangerous and it doesn't do anything."

It was 11 o'clock on Tuesday morning and he spoke before a crowd of researchers in Vancouver. Even for a city that is home to North America's only supervised safe-injection site for heroin addicts, Van den Brink's proposal represents a radical departure: he wants to help alcoholics go on drinking.

According to the World Health Organisation, the European region has the world's highest proportion of illness and premature deaths caused by alcohol abuse yet medical needs to treat alcoholism are unmet.

In the United States, an estimated 17 million have an alcohol-use disorder; nearly four million show a dependence and yet only one million are in treatment.

Alcoholics Anonymous generally frowns on the use of prescription drugs because they "threaten the achievement and maintenance of sobriety". The programme can and does work for some, but, despite its prominent role in culture and its prevalent use in court-mandated rehab, it's not for everyone. In fact, the vast majority fail to stick with the programme. In 2006, a review of alcohol treatment studies by the Cochrane Library, concluded: "No experimental studies unequivocally demonstrated the effectiveness of AA or TSF [twelve-step facilitation] approaches for reducing alcohol dependence or problems." According to The Sober Truth, a book published earlier this year, Dr Lance Dodes and his son Zachary Dodes reviewed the literature and concluded that the overall success rate of AA was only 5 to 8%.

Van den Brink strongly believes that reduced drinking is a viable treatment goal for alcohol-use disorders. If addicts who have 100 drinks per week can stop at 25, he says, then they may also regain control of their lives. There's some precedent: harm-reduction has been shown to be effective in treating heroin addicts.

Reduction could be exactly what many of the 92 to 95% of AA dropouts need. Robert Swift, a professor of psychiatry at Brown University in the US, believes abstinence is usually the best option to treat alcoholism. But he also believes that "one size does not fit all. So there may be people who really cannot drink even one drink, and then there are people who can go back to social drinking."

Swift said he had regularly treated a patient who has trouble staying abstinent between Thanksgiving and New Year's. "He comes in to take medication just those three months," he said. "That's the targeted approach. The rest of the year he's fine, but just there's too much alcohol around during the holidays."

The key for those who don't respond well to abstinence-only interventions, Van den Brink, who co-founded the Amsterdam Institute for Addiction Research, believes, is a pill to curb drinking. The drug is called nalmefene, and it acts as an alcohol antagonist. Simply put, the drug binds to opiate receptors in the brain and reduces the rush of pleasure associated with alcohol. (It has also been tested, with less success, to treat compulsive gambling.)

In one double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, sponsored by Danish drug manufacturer, Lundbeck A/S, Van den Brink and his colleagues studied 604 people who took the drug as needed.

"We say, 'Just take the medication in case you go drinking. Actually, you can even take it the moment you start the first drink.' This brings some of the responsibility back to the person."

Over six months, they found that those taking the drug reduced the number of heavy drinking days from 19 to 8 days per month. Van den Brink admits there is also a profound reduction in consumption with the placebo, which nearly halved daily drinking (from 85 grams to 45 grams) – but the effects were amplified with the nalmafene tablet, which cut drinking by two-thirds (an average of 84 grams to 33 grams per day, or the equivalent of drinking a large glass of wine instead of an entire bottle). Two later studies, published in European Neuropsychopharmacology and Journal of Psychopharmacology, had similar results.

Today, the drug, sold as Selincro, is currently available in Europe. In August, a clinical trial began enrolling patients for a similar US study.

Nalmefene is part of a growing number of pharmaceutical options. For instance, a review paper published in JAMA earlier this year by Daniel E Jonas, a researcher at University of North Carolina, highlighted the effectiveness of drug interventions. Two other opiate antagonists, naltrexone (Revia) and acamprosate (Campral), have been approved since 2006 and help patients refrain from drinking. Jonas found that, overall, these medications remain under-used; they face long-standing scepticism; primary care doctors can be reluctant to prescribe – either because they're not aware the drugs exist, they're not comfortable prescribing, or they've been taught to refer patients to specialists (who aren't available in many areas).

The new approach not only runs up against an entrenched model but some critics contend the latest research on nalmafene found modest, incremental decreases in heavy drinking days – at great financial costs. (A month of treatment costs $140.) In a recent op-ed published in the British Medical Journal, Des Spence, a Scottish doctor, argued that the drugs are little more than a commercial venture taking advantage of the most vulnerable.

Van den Brink takes the criticism in his stride. He says the studies have gone through peer review and been deemed cost-effective by health agencies.

"It's an effective medication that is going to help some people. And it's going to bring some change in our thinking about the treatment of alcoholism. We don't have to use too big words, but there is a paradigmatic shift there."