A few years ago, Isabel Huerta, a mother of two living in Valencia, would never venture into a branch of Spain's leading department store, El Corte Inglés, on a Saturday. "It was always so crowded," she says. "You couldn't even get inside the changing rooms." Not any more. Nowadays, you can drop into any of the four stores in the city on a Saturday afternoon and browse in peace. The aisles, she says, are almost empty. Assistants pursue the few customers that do bother to show up around the shop floor, doggedly chasing an increasingly elusive sale.

Even for the undisputed royalty of Spanish retailing, these are humiliating times but the travails of El Corte Inglés serve as a reminder that no one is immune from the chill that has descended on the country's consumers. According to Spain's official statistics office, the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, in 2008 the average Spanish household spent €31,711. Over the following five years that figure fell consistently, dropping to €27,098 last year.

That's a pretty steep decline, but it tells only part of the story because these figures take no account of inflation. Prices in Spain went up about 9.5% between 2008 and the end of 2013. This means that simply to keep up with rising prices a person would, in theory, have needed to spend nearly €35,000 in 2013 to buy the same quantity of goods and services that €31,711 would have bought in 2008. But instead of going up by 9.5%, household spending dropped by 14.5%. After allowing for inflation, Spanish households spent very nearly 22% less in 2013 than they did five years earlier.

Averages, of course, are not necessarily very informative. They capture a huge range of data from the wealthiest families to the poorest, and churn out a middle-ground figure that reflects everybody to some extent and nobody completely. But when an average falls that far that fast, it is a safe bet that very large numbers of people are cutting their spending to the bone. And when we consider that, thanks largely to the collapse of its construction boom, Spain now has adult unemployment of about 25% – three times the level in 2007 – and joblessness among the under-25s of nearly 54%, it comes as no surprise.

Very similar things are happening right across the southern part of the Eurozone, but nowhere more brutally than in Greece, where adult unemployment stands at about 27% and youth unemployment is double that. Again, however, those figures do not tell the whole story, according to financier Andreas Zombanakis.

"You have to look at the 1.5m headline unemployment number in a different way because you have a theoretical workforce of about 4.5m people in Greece, of which the wider public sector including the electric company, for example, makes up about 1 million. The public sector has had no redundancies, none, zero. So the private-sector workforce is about 3.5m people, and out of that 3.5m you've got 1.5m unemployed – you're looking at almost one in two. And then you've got the other mind-blowing statistic, which is that 400,000 families today in Greece have no one in employment."

Shocking though such statistics are, they are not new. People across the southern Eurozone have been feeling the economic screws tightening on them for a long time. The biggest falls in output and sharpest rises in unemployment were in fact a couple of years ago when the Eurozone crisis was at its most acute. Back in 2012 and early 2013, retail sales in Spain were falling at up to 10% year-on-year. Now the decline has slowed to less than 1%.

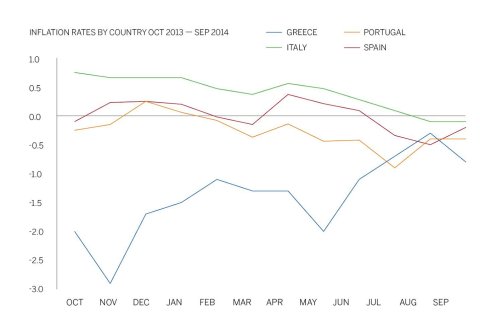

But even as the pace of collapse has moderated during 2014 and perhaps even bottomed out, something else has changed. Inflation rates have fallen steadily across Europe and, more recently, attention has focused increasingly on a new threat: deflation.

The prospect of inflation turning negative for any length of time is one that alarms the great and good of the world economic order, so much so that few of them like to speak openly about it. In January, Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, broke ranks, warning that the threat was growing. "With inflation running below many central banks' targets, we see rising risks of deflation, which could prove disastrous for the recovery," she told an audience at the National Press Club in Washington DC. "If inflation is the genie, then deflation is the ogre that must be fought decisively."

The Genie and the Ogre

When Lagarde made those comments, inflation in the Eurozone had already fallen to 0.8%, well below the European Central Bank's target of "below but close to 2%". Since then, it has more than halved to 0.3%. If deflation really is the ogre that Lagarde suggests, its footsteps seem to be getting louder.

In some places, it has already arrived. Greece's inflation rate has been slightly negative for more than a year; in Portugal inflation has been negative for 10 of the past 12 months; inflation in Spain weakened significantly about a year ago and has been bouncing around zero ever since, with the most recent monthly readings the weakest so far. Italy, meanwhile, now seems to be heading down the same path, recording its first negative year-on-year inflation figure in August, at -0.09%.

Why does the prospect of deflation get policymakers so worried? The explanation is that deflation is a symptom of extremely weak demand. This leads to a slowdown in economic activity and less investment by companies, which see no point in expanding and creating jobs. Profitability and wages therefore remain subdued and the result is lower trend rates of economic growth that have, in the past, proved extremely hard to reverse.

So far, so gloomy. The real problems, however, stem from the effect that this process has on our ability to deal with our debts. When prices are rising at more normal rates incomes usually follow suit with the result that, over time, our ability to support a given level of debt – whose value is fixed – gradually improves. By the same token, periods of very high inflation can quickly erode the "real" value of debt, making it much easier to repay.

Deflation puts that process into reverse. Prices and incomes decline and this means that, relative to our income, the value of our debts gradually goes up. Where inflation lightens our burden, deflation makes it heavier.

Philippe Legrain, who was independent economic adviser to the former president of the European Commission, José-Manuel Barroso, argues that it is Europe's debt levels that make the present situation particularly worrying.

"The existential threat is the huge debt, both private and public," he says. "The focus tends to be almost exclusively on public debt but, actually, everywhere apart from Greece and Italy private debt is much more substantial. If you look at the combined figures for public and private debt, there's been a significant reduction in the US and some in the UK, but there's basically been none at all in the Eurozone and in fact in some cases there's higher debt now than there was seven years ago.

"So we've had seven years of crisis and no progress in tackling the underlying problem, which is why I laugh when officials say the crisis response is working." Their error, he says, is to highlight the current, slower, rate at which debt is accumulating, rather than concentrating on the huge pile that has already been accumulated. "Until you're in a position to bring down that debt Europe is going to be in big trouble and vulnerable to much worse."

Deflation is part of "a continuum of problems", says Legrain. "If you have very low inflation it makes it much harder to bring down debt and if you have deflation it's harder again, but I wouldn't fixate on whether inflation is plus 0.2% or minus 0.2%," he says. "With the huge mountains of debt we have now even very low inflation makes it extremely difficult to grow out of the problem."

The Mileuristas

To many people, Legrain's analysis accords with the reality they are experiencing – fractions of a percent either side of zero makes no difference to everyday life. Ximo Barranco teaches economics in a Spanish secondary school and, even though he's aware that Spain's inflation data suggest prices are falling, he hasn't noticed any obvious signs of this for himself. What he has experienced, however, is one of the harbingers of deflation – wage cuts. His salary has been cut twice over the past couple of years, once by 8% and once by 5%. When people are learning to live on significantly less income, the cost of living will still feel prohibitive even if the official data says prices have stopped rising. Ximo says that even though he is earning less than before, he is now making greater efforts to save and that many more people he knows are doing unpaid overtime than used to be the case.

Like many others, however, he is happy just to have a job. Working for less money beats unemployment in a country where, once unemployed, the chances of staying that way are high. At the end of 2007, less than one in five of Spain's unemployed had been jobless for more than a year, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. By the end of 2013, it was more than 50%. In Greece, it was more than 70%.

Between 2009 and 2013, "real wages" (i.e. after taking inflation into account) fell 2% a year in Spain, just over 2% a year in Ireland and Portugal, and 5% a year in Greece. The OECD recently warned that this trend posed a growing threat. "Any further reduction of wages risks being counter-productive because then we would run into a vicious circle of deflation, lower consumption and lower investment," said Stefano Scarpetta, the organisation's director for employment. One telling sign of the shift can be found in the Spanish term mileurista. Back in Spain's boom times, this was a slightly disparaging label for someone who earned €1,000 a month, implying pity that they couldn't get a better job. Nowadays, people tend not to use the word in that way – many Spaniards today would be happy to be called a mileurista.

Anthem For Doomed Youth

Conditions like these are prompting pronounced shifts in behaviour and attitudes in the "crisis countries" that make it more likely they will continue on the path they seem to be on. Jorge Martin, an analyst covering Spain for the consumer research company Euromonitor, argues that one of the surprising things about the country's downturn has been the relative lack of social unrest that has accompanied the crisis. The buffer in Spain and elsewhere has been the strength of family ties, which have seen most young people give up on the idea of moving out of their parental home and many older offspring move back in. And the young are not the only ones returning, says Martin.

"A lot of people are taking their elderly relatives from retirement homes and bringing them back to live with them in order to be able to live on their pension and to support the expenses of that household." State pensions, he points out, offer a guaranteed source of income to families that are struggling.

Andreas Zombanakis says that in Greece similar things are happening, although, because urbanisation was a more recent phenomenon, the process has brought with it an added layer of dislocation and disillusion. "The generation that hit adulthood in the 1960s and 1970s probably did six years of school and then went to work on farms but as they got wealthier they wanted a better life for their children." Many of these youngsters remained in education and progressed to trade schools or university, but, since the crisis, huge numbers of the jobs they went into have disappeared.

"Suddenly these people are returning to the land because they're unemployed," says Zombanakis. "They're going back to their villages in order to survive because in the village you can eat so at least you won't go hungry. Now that generation is being forced to take on jobs as farmers, so you have two generations that have had their dreams and their efforts come to nothing. You have the electrician or the carpenter or the bank employee who is now back doing what his parents did. And you have his parents, who made all these sacrifices to educate their kids and who suddenly see that all this effort was for nothing. You've shattered the dreams of two generations."

For many younger and better qualified people, moving back in with their parents is only a stopgap. Ultimately, a growing proportion of them will leave the country in search of better pay and greater opportunity.

Felipe Rueda graduated from a Spanish university in summer 2013 and, like almost all his contemporaries, found it impossible to land full-time work of any sort. Along with several of his friends, he registered as self-employed and found that this enabled him to start earning, albeit at very low rates.

"It seems to open more doors than if they have to give you a contract and pay your social security," he says. "A lot of the people in my year, on my degree course, are self-employed for that reason. You have to be a bit cunning. There are people who won't give contracts to friends of mine but they tell them, 'Look, register as self-employed, invoice us for half and we'll pay you the other half on the black.' I know of several cases like that. They're getting €6 or €7 an hour but they're happy because they're working."

Rueda has set his sights on escape. He is attending language school to improve his English and says his girlfriend has already looked into securing visas for the US. "I accept it as a positive thing, like an adventure," he says. "If my country won't offer me work, well maybe there are other countries that want me."

Emigration from Spain is rising quickly. Having seen an enormous inflow of immigrants mainly from South America in the decade or so to 2010, the country's population is officially forecast to shrink by about 5% over the coming decade largely as a result of immigrants returning to their countries of origin. Leaving alongside them, however, will be a growing number of younger Spaniards like Rueda and, unfortunately for the Spanish economy, they will often be university graduates with high earning potential – the next generation of middle-class professional taxpayers.

If large numbers of unemployed migrants leave, that may be a blessing in the short term if it eases the burden on overstretched welfare systems. But losing well-qualified members of their workforce will naturally make it harder for crisis-hit economies to return to the kind of growth rates that will help them to stabilise, and eventually reduce, their huge debt burdens. Even before the financial crisis, Europe was facing a looming problem thanks to low birth rates and a growing number of elderly citizens who will rely on the taxes paid by a shrinking band of younger workers to fund their pensions. The economic disaster that hit countries such as Greece, Spain and Portugal has tilted the balance further towards the danger zone.

No More Babies

The statistics on numbers of live births tell a worrying story across all these countries. Between 2008, when the number of live births reached a short-term peak in Italy, Greece, Portugal and Spain, and 2013 the number of babies being born each year went into a dramatic decline. In Italy, the total dropped nearly 11% and it looks likely that within the next year or two, fewer than 500,000 babies will be born per year in Italy for the first time since reliable records began. Spain saw its total number of live births drop 17.9% over the same period, Greece fell 20.4% and Portugal 20.8%.

"Most of my friends don't think they will be starting families in the near future because they don't have stable jobs. They're worried and they think they will have to wait for a long time," says Cathy Camarasa, a 32-year-old Valencian with a four-month-old daughter. She expects to return to work shortly, since her maternity pay runs out after 16 weeks.

The collapse in birth rates across the southern Eurozone stands as the clearest indicator of how profoundly the economic crisis has changed the way people think and behave. "It's a sign of a sick society when people are afraid and don't want to take on the financial burden of a baby," says Legrain. "I think it's quite a rational reaction. You saw the same thing with the break-up of the Soviet Union." And this change is likely to have a long-term effect on these countries, further reducing the potential of their economies to grow and escape their debt burdens, and deepening the problems that lie in wait within their pension systems.

The Informal Economy

People's belief in the ability of the state to help and support them has already been severely undermined, partly because governments have cut services and pushed up taxes in order to repair their own threadbare finances. To some degree, increases in taxes such as VAT temporarily pushed up the rate of inflation by increasing the prices of goods and services, in the process ratcheting up the pressure on stretched household budgets.

By common consent, this has increased the size of the black market in these countries. Money that should go to the state to finance public services instead goes under the table – employers are only willing to take on people like Rueda and his friends if they can hire them as self-employed contractors, thereby avoiding employers' social security contributions, and can pay half their wages in cash. That makes the financial position of governments worse but it helps to cushion the austerity for some people at least.

"If they thought tax evasion was bad before the crisis it's worse today and that in a way for me explains why life on the streets is better than the official statistics show, because the black economy is still big," says Zombanakis. "And the reason I say that is when you've got a country where the vast majority of businesses are very small, tax evasion is high because it's in the nature of the small trader. So when the plumber comes to your house to fix your toilet cistern and he asks for €100 in cash or €123 with VAT, you'll give him €100 in cash. That's a rational response. He saves money on his income tax and you pay less VAT."

Similarly, Yannis Palaiologos, an Athens-based journalist and author of The 13th Labour of Hercules, a recent book on the Greek crisis, says that many Greeks who are able to get away with it, avoid paying pension contributions.

People have more immediate uses for their cash and, in any case, there's a widespread assumption that the Greek pension system is bust and therefore will not be able to support them when the time comes. However, he adds that over the past 18 months government efforts to improve collection rates and reduce levels of black market employment have been making inroads.

'Goldilocks Deflation'

Of course, a major part of the reason that governments in the Eurozone's crisis countries have been pushing up taxes such as VAT is that they are under acute pressure from the authorities in Brussels to cut their borrowing and bring their huge budget deficits under control despite the obvious risks of increasing taxes at the same time as wages are falling and unemployment is high. This, however, is part of the Eurozone's policy for dealing with its problems.

In January, the president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, wrote to the Dutch MEP Auke Zijlstra, that "very low or negative inflation rates for some countries reflect the necessary temporary adjustment and rebalancing processes", assuring him that deflation "is not something we see or expect to see at the euro area level". Others, particularly in Germany, are even more candid. Hans-Werner Sinn, head of Germany's influential Ifo Institute for Economic Research, wrote recently that "deflation is not a danger for southern Europe but an essential precondition for restoring competitiveness".

Draghi's letter, however, begs some crucial questions. How can anyone be sure that this period of ultra-low inflation in southern Europe will turn out to be a "temporary adjustment" and that things will pick up again once the "rebalancing processes" are complete? And how can they be certain that it won't spread northwards and encircle the Eurozone?

In the years before the financial crisis, economists used to talk about a Goldilocks economy that was neither too hot and therefore at risk of excessive inflation, nor too cold and at risk of recession. Implicit in the remarks of figures such as Draghi and Sinn is the idea that it is possible to have "Goldilocks deflation" – enough to cure the patient without killing him – and that it will be possible to reverse the process when they judge it has gone far enough.

This belief lays bare perhaps the greatest risk to the future of the Eurozone economy – that officials trying to guide its course are subject to the "illusion of control", a well-documented psychological bias that leads us to believe we can shape processes that are in fact immune to our influence.

And they may be encouraged in this belief by the strange phenomenon of so-called "inflation expectations". In judging the risks of inflation or deflation, economists tend to rely on indicators of what people expect inflation to be in future, derived either from prices in the bond markets or from surveys of consumers.

The problem is that both are proving extremely unreliable.

Anchors Away

Bond market measures of inflation expectations have provided no early warning of the steady fall in inflation that the Eurozone is now witnessing. Instead, they have continued to signal a belief that prices will rise at around 2% a year. The consistency of this message has been important to Eurozone officials and has been taken to indicate that there is little imminent threat of deflation. Inflation expectations are said to remain "well anchored", in the jargon, although recently market forecasts have belatedly started to weaken.

Surveys of consumers give very similar results. For example, an inflation expectations survey carried out quarterly across several countries for M&G, a UK asset manager, consistently shows that consumers expect inflation to be roughly what it has been over the past few years. In August 2013 consumers in Spain said they expected inflation one year ahead to be 2.8%. In fact, Spanish inflation in August 2014 was -0.4%. When asked the same question in August 2014, they forecast that inflation in a year's time would be 2%.

All in all, putting any degree of faith in inflation expectations to tell us whether we're on the right track looks pretty unwise.

"The fall in inflation over the past year happened without anyone expecting it," says Philippe Legrain. "Obviously, if people start expecting deflation and that shapes their behaviour then it is harder to get out of it, but you can still get stuck in deflation without people anticipating it in the first place.

"Expectations can be lagging – they don't need to anticipate. If you're an economist you think they anticipate but that's because economists take a different view of the world than most people."

In effect, that means that by the time people start saying that they expect deflation it will already be well advanced because their expectations are shaped by the recent past, not by any particular insight into what is going to happen.

One possible – even likely – future for the Eurozone, according to many commentators, is that it will follow the path that Japan has trodden for the past 20 years, since the aftermath of its own financial bust in 1989.

"My baseline scenario is Japanese-style stagnation – i.e. a prolonged period of very low growth, very contained price rises and bouts of deflation, and underlying that a failure either to write down excessive debts or to tackle once and for all the problems in the banking system, which of course are linked to the extent that those debts are owed primarily to the banking system," says Legrain. The worrying aspect of this parallel is that once deflation set in, Japan has found it all but impossible to bring it to an end and even decades later is still struggling to escape it.

Rather than paying attention to what people think will happen to inflation, anyone looking for clues about the immediate future in the Eurozone should take a look at what people say when asked about matters rather closer to home – what they expect to happen to their own net income over the next 12 months. Everywhere we turn the vast majority think they will be getting the same or less a year from now. The most recent data for France is particularly striking: 48% of people are expecting a pay cut in the coming year, by far the highest proportion in the M&G survey.

Confining the ogre to southern Europe might turn out to be harder than we thought.