Where the road turns right at the water tower and heads down to the hamlet of Gibret, a grain silo sits outside a large low-slung shack on a sunny hillside. There are commanding views of rolling valleys dotted with spinneys, rich fields of crops and smallholdings. A stream bubbles past as a common crane wheels lazily over the golden expanse of maize.

But this is a rural idyll with a difference. Open the shack door and the dim neon lighting illuminates the other windowless face of bucolic South West France, an hour's drive east of Biarritz. Once in the fetid heat, we quickly realise that the sound of the stream is an illusion caused not by water sussurating over a bed of pebbles, but by an old fan blowing through what looks like a giant car radiator.

Welcome to Bellevue Farm, a production line for the area's biggest business: foie gras. It is lunchtime on the day of our unscheduled visit. Farmer Vincent Dages' voicemail picks up our calls. No one responds to the ring on the doorbell or to the knock on the shack door, which is closed but not locked. It is, after all, lunchtime in the Landes, and lunch is still important here.

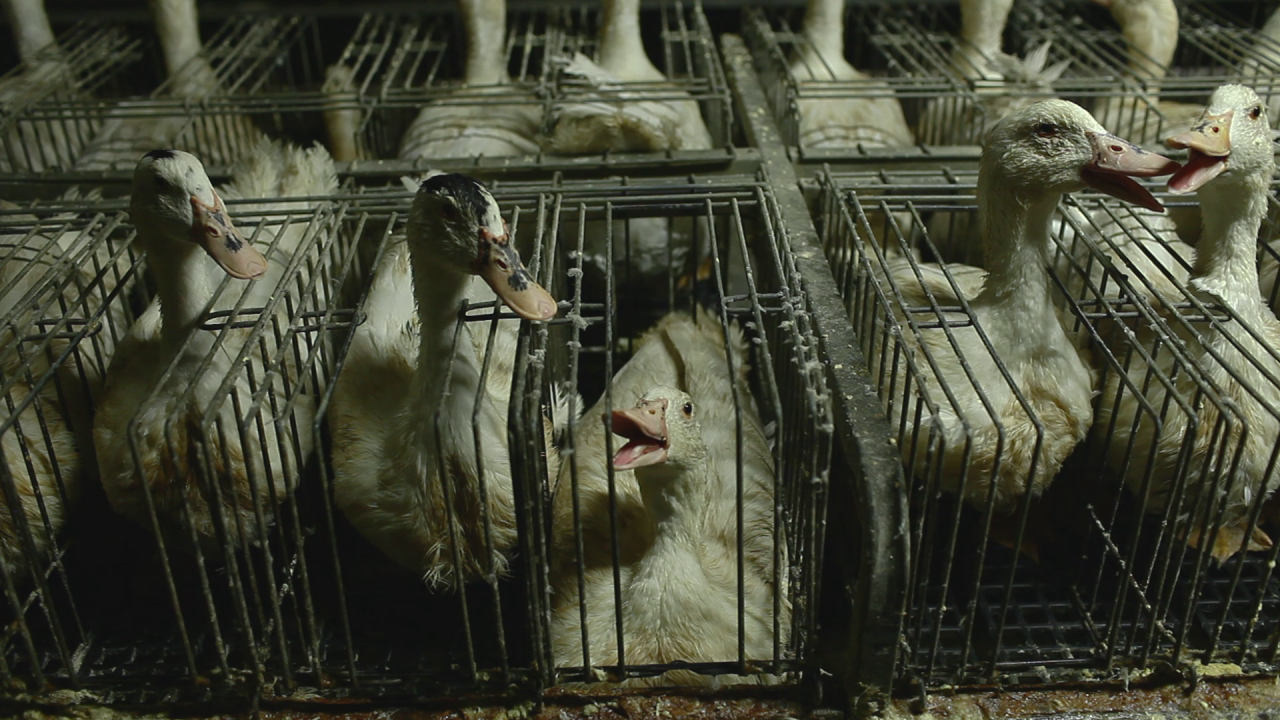

During the long summer months in this 50m long hut, the fan groans to keep the temperature below 25C, as 850 or so mullard ducks face the last days of force-feeding before the short trip to the abattoir. They are crammed into individual cages that have a gap just wide enough for their heads to be accessible to the "gaveur" – the man force-feeding the birds – who, in the space of two-three seconds, will cram up to a kilo of thick yellow mash made from boiled maize into the birds' gullets via a long metal tube, at twice daily intervals.

"This is like cramming 20kg of pasta into a human being, twice a day for two weeks," Brigitte Bardot, the legendary actress and animal rights campaigner tells us from her home in Saint Tropez. "Imagine the food being forced down a tube into your stomach while you are in a cage in which you cannot move."

Silence greets our entry, for these ducks are mute, like the other cross-bred mullards used for foie gras and duck meat production. They are also sterile, incapable of flight and often lame from foot infection due to standing on metal grilles during the gavage (the grilles are there so that copious defecations, caused by breakdown of the liver from the unfeasible volume of feed, can flow into the troughs below).

It is not a pretty sight. The birds are listless, they have turned from white to a yellow tinge and are greasy with oil produced to keep the water out. They are incapable of preening themselves because they are wedged in cages too narrow to allow much movement once their body weights have increased from around 4kg to 6kg, during the 12-day gavage. But if we view farmer Dages's web page on the site of Excel, which is one of the biggest producers of industrial foie gras, Bellevue is made to look like an idyllic place – something from the pages of Beatrix Potter.

Dages's operation is huge compared to the small traditional farmers who still operate in the Landes and Gers. But, in terms of the expanding industrial market, he is of little significance. He stuffs the livers of 17,000 ducks a year on behalf of Delpeyrat, one of several large firms furnishing the global market for what was once a seasonal local delicacy.

Nearby, in a leafy lane outside the village of Poyartin, is Christophe Muret's farm. He has three large gavage units, each capable of dealing with 1,500 birds, producing an estimated 60,000 fattened livers a year for another giant, Euralis. The sheds are firmly bolted and our arrival is greeted by a man in overalls who is unequivocal about showing us inside. "Non," he says firmly, handing over his boss's mobile number.

These are two of many local farmers close to the old rugby town of Dax who supply the food giants with the 38 million or so fattened duck livers the international market requires, despite recent bans on ethical grounds by more than a dozen countries, including India, Israel, Germany, Norway, Poland, Sweden and Switzerland.

This is also despite the ban imposed by Brussels on many of the industrial methods still deployed throughout France. Technically, people like Dages are operating illegally by using individual cages, but France has been given licence until the end of next year to sort this out. It might not be easy given that 95% of total foie gras production comes from the industrial giants.

According to Sébastien Arsac, a founding member of L214, a French animal rights organisation, the collective cages, which will replace the individual cages in 2016, are no better than the individual cages. In the collective cages five or six male ducks are crammed together.

"When it's force-feeding time, the metallic front side of the cage is lowered on the ducks by remote control. The ducks are crushed underneath making it easier for the "gaveur" to insert his tube into the gizard. Most ducks end up with multiple fractures at the end of a gavage, while mortality increases as the gavage approaches completion, usually after 12 days.

"These two types of cage were designed in the 1980s when foie gras production was industrialised. Prior to that, ducks were always force-fed in 3m by 1m enclosures. That's the solution that should have been chosen by the legislators, but the big industrial guys were not interested."

This video, filmed by the writers, shows force-feeding at a small 'ethical' farm in South West France where the birds are fed 200g of par-cooked maize. Although it may look brutal, it is nothing compared to the big industrial cages where up to 1,500 birds are fed at an average of 2.5 seconds per bird. During this time up to 1kg of gruel is blasted down the gizzard of the duck.

There is such anxiety about the forthcoming legislation that plans were hatched to move foie gras production to China, where animal rights are low on the agenda. The problem now is that the Chinese, having learned how to make foie gras from the French, want to run the show on their own. Imports from France were banned in April this year, and the Chinese are said to be planning to satisfy their own internal market, estimated at 130 million. This trend is horrifying animal rights advocates in the West, who say there will now be no ethical constraints on foie gras production.

In Paris, TV celebrity chef and former Masterchef presenter Yves Camdeborde, who is a great fan of foie gras, says the industrial production methods are a disgrace and a matter of national shame. "As soon as any product becomes industrial, it is the end. This applies to veal, pork, milk produce and many more things," he said. "The problem is that the agroalimentaires have enormous influence over the government and you just can't get anywhere. They have introduced a series of labels to make everything look authentic, but it is a mere smokescreen."

Camdeborde's supplier, Sandrine Lesgourgues, runs Paris Foie Gras & Confits from Pomarez near Dax. Her family has been in business since 1907. She and her husband, Maurice, a former trainer of the Biarritz Olympique rugby team, buy only from small local outlets which follow their guidelines on production to the letter. "We are having increasing trouble finding small, ethical producers and we fear for our business," said Lesgourgues. "The big boys are buying up the small producers and slowly squeezing people like us out. They want complete control.

Some 97% of foie gras comes from ducks, the remaining 3% from geese. And foie gras only comes from the males. Which begs the question: what happens to the female mullards? "They go into industrial grinders for destruction," said Arsac. "We are talking roughly 40 million ducklings who are thrown live in the broyeuse." The ground-up ducklings are collected by the processing plants which take care of the residue of the slaughterhouses. In these plants, organic waste is used to produce cat food or fertilizers but also for the pharmaceutical industry.

This video, filmed by activist group L214 on a foie gras farm in Landes, shows workers throwing female ducklings into a grinder to be turned into pet food. Foie gras is only produced from male ducks, so the females are surplus to requirement.

The British actor Roger Moore says he refuses to attend dinners if "torture in a can is on the menu". Moore's views on foie gras add considerable heft to the efforts of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta), whom he endorses heartily.

"Once upon a time, I ate foie gras, as was the fashion at parties and dinners, but that's when I was ignorant of just how it was produced," he says. "Force-feeding birds such an enormous amount of food every day causes their livers to swell to an enormous size and results in a disease known as "hepatic steatosis". The birds often suffer from internal haemorrhaging, fungal and bacterial infections and hepatic encephalopathy, a brain disease that occurs when their livers fail."

The Landes is the single biggest foie gras producing area in the world. On the outskirts of its préfecture, Mont-de-Marsan, is a shiny white citadel high security fences. It measures approximately 160,000 square metres and its ground space looks considerably larger than the Airbus HQ we can see from the Toulouse ring-road.

This is the headquarters of Delpeyrat, one of the market leaders. Again, a tour of the huge production line was not possible. It is the likes of Maïsadour, owners of Deylpeyrat, and Euralis who call the shots, and the French government which does their bidding. A tour of its building was denied to Newsweek and an email requesting information went unanswered, as did several phone calls.

"The only glimmer of hope can only come from consumer awareness," says Arsac.

One company leading the way in ethical production is Patería de Sousa from Spain, which has supplied food to the White House. They do not use gavage but instead allow their free-range geese to gorge of their own free will prior to winter migration before harvesting the livers. But there is a price for this: around €833 a kilo, before tax.

Marie-Pierre Pe, a spokeswoman for CIFOG, the Interprofessional Committee for Foie Gras, which represents the giant producers and works hand in hand with the French Ministry of Agriculture, says she objects to the use of the word "industrial".

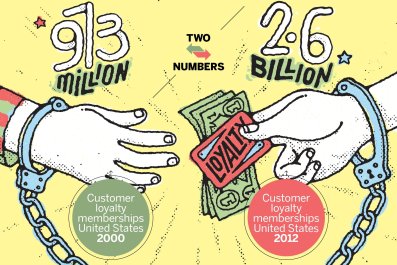

"It is pejorative," she says. "Whether the gavage area has 200 ducks or 1,000, the feeding process is the same: a one-on-one process between feeder and duck, a precise activity that has been going on for generations. There is no difference in procedure between the small and large producer." CIFOG says that the foie gras industry last year turned over €1.6bn.

Pe says the ducks are kept in the best possible conditions and that €100m has been invested in "upgrading" the cages from individual to collective, but that there were still 500,000 individual cages in use. She also denies that up to 4% of the animals died during gavage and said it was " more like 1-2%".

Opponents of gavage are "foremost a group of militant vegetarians and vegans who accord equal rights to animals and humans alike," she declares.

"We respect their right to hold that opinion but the anthropomorphic image they peddle is completely erroneous because ducks, while they are sentient creatures, are not human beings. For instance they have no gag reflex," Pe concludes.