No game is just a game, but cricket carries more baggage than any other sport. For all the nations mad enough to play the game seriously, cricket is inextricably intertwined with national history and national identity. That's doubly true in England, where they invented the game, even if it's claimed in India that cricket is an Indian game that was "accidentally discovered by the British".

Cricket is traditionally linked with certain moral virtues: duty and self-abnegation in the face of a common cause. When the Gatling gun's jammed and the colonel's dead, the troops on the borders of the Empire are rallied by a cry from the cricket field – "Play up! play up! and play the game!" – in the 1892 poem Vitaï Lampada by Henry Newbolt.

Cricket is linked with the Golden Age of English power and self-content, the idyll that supposedly existed before the First World War. Francis Thompson wrote of the time when "a ghostly batsman plays to the bowling of a ghost": nostalgia for an idealised and largely imagined past. That notion is as much a part of cricket as a leather ball.

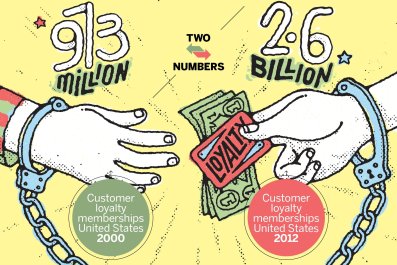

Moral virtue. Empire. A sense of place. Timelessness. A fully realised society. Above all, loyalty. Cricket was seen as an arena where the privileged and the less-privileged met in shared amusement and common cause. As the historian G M Trevelyan wrote: "If the French nobility had been capable of playing cricket with their peasants, their chateaux would never have been burnt." In cricket there was always a sense of the past flowing effortlessly into the present without losing its savour.

So, fast-forward a century or so and you find a media feeding frenzy. Kevin Pietersen, as talented a cricketer as ever picked up a bat, is at the heart of it. Earlier this year he was sacked from the England cricket team: earlier this month he published a book, KP: The Autobiography. Like Hamlet, it is as devoted to the concept of revenge, but the autobiographer lacks the prince's humility. Pietersen said a colleague who betrayed him was "worse than Judas", which can only mean that Pietersen seems to imply he's better than Jesus.

In reply, the England and Wales Cricket Board leaked some information to ESPN's Cricinfo website with counter-claims about Pietersen, alleging behaviour calculated to bring out the vindictive bitch in Mother Theresa and incontinent fury in Job.

Pietersen played for England but he came to England from South Africa because he was fed up with the quota system, which fast-tracked non-white South Africans into elite sport. He has an English mother, and, after a four-year qualification period, he was selected for the England team. He soon proved himself a batsman of unconventional brilliance, but he never entirely got the notion of the team – still less that of self-abnegation and duty.

Rock bands tend to suffer from LSD or Lead Singer Disease. The front-man gets so full of himself that everybody (a) hates him and (b) can't do without him. It's evident in the film The Commitments and the history of Guns N' Roses: the glorious beginning, the lofty peak, the break-up caused by "musical differences". It was exactly like this with Pietersen and England. Such tensions are found in all team sports, but top level cricket, requiring players to be in each other's company for months on end, has more scope for clique-forming, rows and feuds than any other.

Cricket's glory is, and has always been, with the international game, particularly Test matches, which take five days. But these days the big money is in the Indian Premier League, in which multinational teams play a version of the game that takes a single evening. No ghostly batsmen, no nostalgia: this is cricket as spectacle: tamasha, as they say in India. It is unrecognisable from the game in those poems. The players wear coloured clothing rather than whites, use a white rather than a red ball, adopt elaborate protective gear, swing huge hi-tech bats with pneumatic muscles to a background of loud music, fireworks, and cheerleaders accompanied by Mexican waves. The Edwardian ritual is gone, but there is serious money to be made here, and the players – Pietersen was always in the vanguard – are desperate to cash in on their fame and their abilities while their bodies hold up and the mad money is still sloshing about.

Money changes everything. In sport, it has shifted the power from the administrators to the players. In cricket, this process began in 1977 when the Australian entrepreneur Kerry Packer bought up all the world's best cricketers and set up a rival circuit. The players went willingly because he paid them in accordance with the rewards that came in from television. It was revolution: the old-school administrators found their châteaux burned. They had shown the foresight of Louis XVI, who said: "The French people are incapable of regicide."

Since then, cricket has become the incredible shrinking game, forever reinventing itself in ever-shorter formats to appeal to more people and make still more money. Five-day Tests still take place, but the more popular and profitable version of the game is played in a single day. Twenty20 cricket lasts less than half that.

The money, and therefore the power in the game, is now with India. India dominates in a manner unthinkable to those cricketing poets. England and Australia are now India's lackeys – and proud to be so, because that makes them a cut above the other seven nations that play top-flight cricket.

Everything changes. At least it does if it isn't dead, and cricket is thriving. But its radical changes are painful to many people. The Pietersen saga is a vivid demonstration of these changes. No loyalty, none whatsoever – not on either side.

Money trumps nostalgia, money trumps sentimentality. The admin's jammed and loyalty's dead. Pay up! pay up! and play the game!