Dr. Senga Omeonga, a surgeon in Monrovia, Liberia, and an Ebola survivor, waited a week after he fell ill in August to be given a bed in the only Ebola Treatment Unit in the city. Liberia, a country the size of Tennessee, has seen nearly 4,000 Ebola cases. But the treatment unit in its busiest city only had capacity for 40 beds. Omeonga was vomiting and running a high fever, quarantined with others awaiting care.

"They were giving priority to health care workers. but even still I had to wait one week," Omeonga says. Between the lack of beds and not enough protective equipment for health care workers, he says, many Ebola patients are refused treatment. "But then [the patients] go back home, and infect their communities. It's a big problem."

The Ebola epidemic has dealt a crippling blow to West Africa's health care infrastructure. As international aid comes into Ebola-stricken regions in shipping containers, what if rapidly deployable Ebola Treatment Units could be in those containers too?

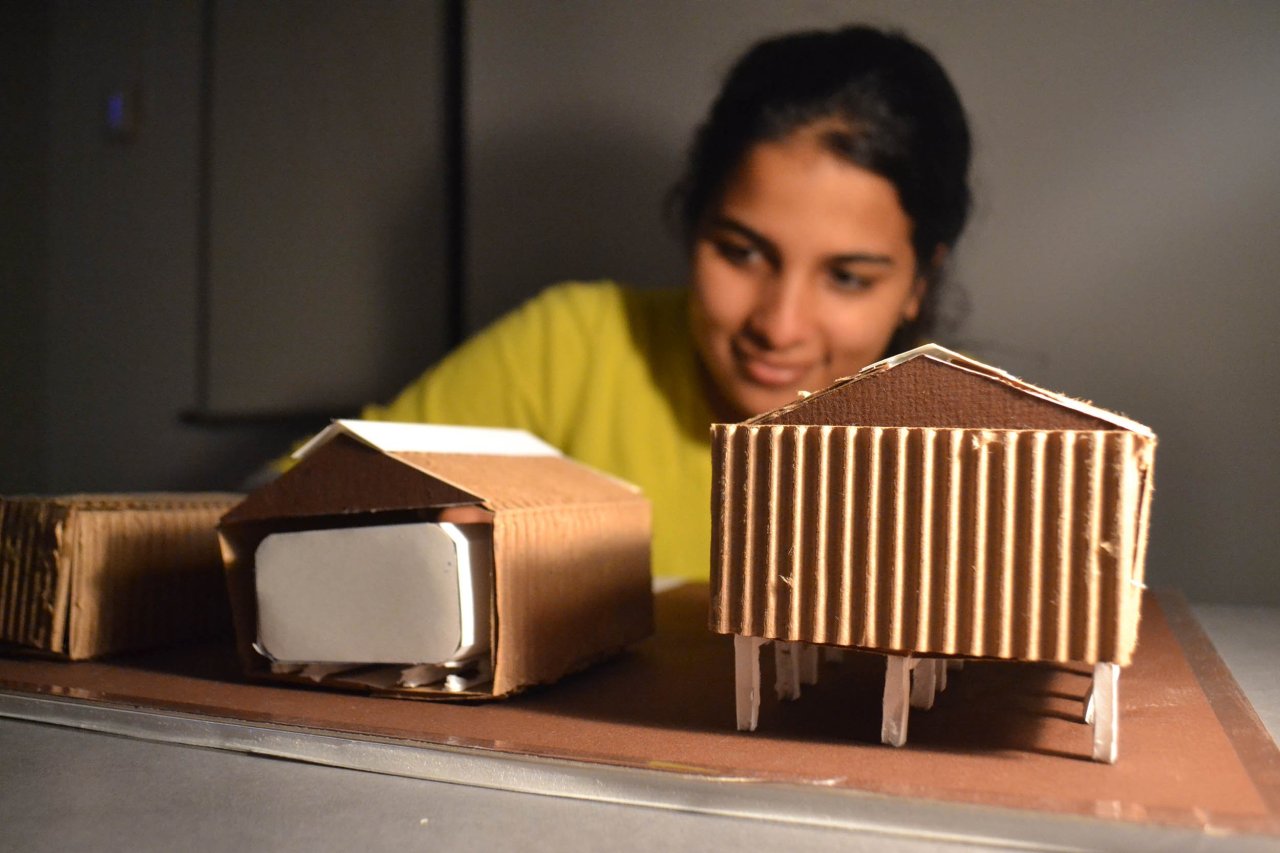

For 13 days, master of architecture students at Texas A&M University worked day and night to design prototypes for such units.

Advised by experts such as retired Air Force Major General Annette Sobel, a specialist in global disease surveillance, the students turned in 11 designs for portable Ebola wards that could be easily shipped in a shipping container or a cargo plane, light enough to be airlifted by a helicopter, and simple enough to be assembled on the fly, in a parking lot or an open field.

"It is crucial that these units not be on the grounds of existing hospitals. Why risk contaminating a whole hospital?" says George Mann, director of a health care architecture studio at the university. The units also had to be air conditioned, and incorporate spaces for health care workers to decontaminate their protective gear. Some designs also included fences and security outposts. "Sadly, when you don't have enough beds, sick people might be trying to come in. Health care workers and patients need to be secure."

One student, Soheil Hamideh, designed an Ebola ward made of a flexible, UV-resistant material that could fold up for compact shipping and then expand, accordion-style, into long rectangular units to accommodate 48 patients. The pop-up wards included decontamination showers for staff, waste-storage units and a morgue unit to keep still-contagious bodies of the deceased far from treatment areas.

Another student, Qianqian Zhang, designed her units to resemble a network of geometric cells. The walls would be made from Polytetrafluoroethylene, a highly waterproof, lightweight synthetic material stretched over a simple beam structure with joining pieces, like a sophisticated hard-sided tent.

P.K. Carlton Jr. a former surgeon general of the U.S. Air Force who helped advise the students, told Fast Company his next step will be to show their designs to members of Congress. The U.S. has devoted millions of dollars towards emergency relief and health care infrastructure in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, but it has yet to announce plans to deploy portable wards of the kind designed by the students.