"All diplomacy is the continuation of war by other means," former Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai once quipped. These days, the same might be said for eurozone summits.

The European Union was founded to ease the continent's toxic wartime legacy, to allow Germany to help lead the continent, not dominate it. But in the aftermath of Greece's most recent bailout this summer, the harsh austerity terms imposed on Greece have created an unprecedented level of animosity between the two countries. Now, as the rancor ripples across borders, many are questioning the EU's political and economic future.

Under the terms of the bailout, Greece receives funding up to 86 billion euros ($94 billion). In exchange, the coalition government, led by the left-wing Syriza party, must implement further austerity measures, increase value-added taxes and liberalize the rule-bound Greek economy. Greece must place national assets worth 50 billion euros ($55.1 billion) into a privatization fund that will be supervised by European institutions.

The Greek parliament approved the deal on July 16, and the backlash was fierce. Zoe Constantopoulou, a Syriza lawmaker, says the bailout terms amounted to "social genocide." Even moderate Greek politicians say the harsh terms of the deal will increase fear, insecurity and resentment in Greece. "There will be very strict monitoring of how Greece implements the new measures, almost policing the Greek economy," says former Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou. "These have been put in place to create trust for the German taxpayer, but will create more distrust for Greek citizens. Greece's access to markets is now more difficult, and some of the revenues simply go back to paying off the debt. Some of the burden should have been taken off."

Meanwhile, the European banks that loaned billions to Greece have escaped any penalty. "If you are a drug addict, you are to blame for your addiction, but the dealer also bears some responsibility," says Denis MacShane, a former minister for Europe and author of Brexit: How Britain Will Leave Europe. "Greece is an easy whipping boy, [but] French, German and Dutch banks lent recklessly."

The result: Postwar Greek-German relations have never been worse, analysts say. The trauma of the bailout is compounded by the enduring trauma of World War II, when Greece suffered one of the harshest Nazi occupations. What has surprised many observers is the ease with which both sides have slid into stereotyping, calling Greece a lazy, feckless nation that can't be trusted, and Germany a Fourth Reich run by Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Greeks who believe the latter point to Walter Funk, the Nazi economics minister and one of Hitler's most important economic theorists. Funk raised the idea of a German-dominated European monetary union in 1940. He recognized that the union would be complicated, in part because of different countries' standard of living. Yet Funk, like many modern-day European politicians, was an optimist.

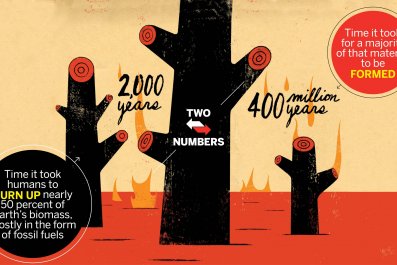

As the Greek crisis shows, however, Funk's faith, like that of the euro architects, was wildly misplaced. A currency union of highly disparate states without a shared central budget and fiscal policy was always going to be hobbled. "Greece," says Peter Doyle, a former division chief in the International Monetary Fund's European department, "is the canary in the coal mine. If the canary dies, it does not tell you that there is something wrong with the canary, but with the mine. Greece is the canary, and the eurozone is the mine."

Burdened by debt, corruption and an over-intrusive bureaucracy, Greece's economy will be hard to repair. What will be more difficult to fix, however, are the mutual misperceptions of Greek and German citizens. "The inability of either side to even begin to understand the other's perspective has inflicted lasting damage," says Ian Bremmer, president of the Eurasia Group, a global political risk consultancy firm. "They aren't really trying to cooperate, because there's so much personal enmity."

Worse still, in the aftermath of the agreement, many observers have begun to question how decisions are made within the European Union. A French diplomat with knowledge of the Brussels negotiations tells Newsweek, on the condition of anonymity, that Germany was the most important voice at the July summit. "We knew that once Germany agreed to the terms it would take 20 minutes to convince the others," the diplomat says. "As long as Germany was OK with it, the other hard-liners would be as well."

But Germany's win in Brussels came at a potentially high cost. "It has challenged the fundamental European value of solidarity and has made other EU member states increasingly question the German role within Europe," says Julian Rappold, of the German Council on Foreign Relations, a Berlin-based think tank. Papandreou agrees. "We are seeing a default to the biggest gorilla in the pack being the one that makes decisions," he says. "That will create even more tension."

Today, 19 countries share a common currency, the euro. But without a common budget and fiscal policy, some analysts say the eurozone is hindered by the economic mismatch between member states; the average household income per capita in Germany is $31,252 per year, but in Greece it's $18,575. By subjecting Athens to such extensive regulation and supervision, some observers say the technocrats may have started the slow death of the single currency—if not of the EU itself. "Everything the Germans did in preparation for the summit, how they organized their demands and their lobbying, was intended to encourage Greece to leave the euro," says Doyle. "It's outrageous. This deal...was never intended to work."

Already, the harsh terms imposed on Greece have boosted the anti-EU movement in the United Kingdom. By the end of 2017, David Cameron, the British prime minister, has promised a referendum on EU membership. Cameron will campaign for Britain to remain in the EU, but most in Britain say the country needs to decide where it stands in relation to Europe. The referendum will do just that.

No matter what happens in the U.K., Europe's leaders have a major dilemma. The eurozone crisis has highlighted how, if the euro is to survive, the continent's fiscal, economic and political policies must come together, which would require changes to the EU's founding treaty. But the financial pummeling Greece has taken from Germany means there is even less appetite for closer relations. As Bremmer puts it: "Europe has become a bloodless institution, an efficiency-enforcement mechanism, rather than a union or a collective aspiration."

Adam LeBor is the author of Tower of Basel: The Shadowy History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World.