It's a summer Thursday, happy hour at Lee's Bar in downtown Rugby, North Dakota, and as millions of Americans prepare for a weekend at the beach, 54-year-old bartender Jeff Ekren doles out drinks and reveals a little piece of autobiography: "Never seen the ocean," says Ekren as he pours a shot of BlackBeard Spiced Rum for one old-timer. "It don't mean much to me."

Ekren's indifference to the sea is common in Rugby, a 3,000-person farming town 45 miles from the Canadian border. Rugby is the official geographic center of North America, which means it is approximately in the middle of the continent, and well over 1,000 miles from any ocean. Some residents joke that they can feel Earth pivoting.

For beach lovers, a life without the ocean might seem like a life not worth living. Consider the long arc of the idea that oceans enhance wellness. The ancient Greeks believed seawater preserved health, and the "thalassotherapy resorts" and "sea-bathing infirmaries" of 18th and 19th century France and Britain catered to the notion that the minerals in seawater had curative properties. More recently, in 2013, researchers at the University of Exeter Medical School published a study in the journal Health & Place that analyzed English census data and showed that individuals living near the coast reported significantly better health.

But residents of Rugby, and the northern Great Plains in general, appear to be a living contradiction. Not only are people here quite healthy; they may be among the healthiest people in America. Data from a 2012 U.S. Census Bureau report show that of the 10 states with the greatest percentage of centenarians per population, six are in the Upper Midwest. And at the very top of the list is North Dakota.

"Here in the Upper Midwest, we don't have that relaxed, sunny Southern California or Southern Arizona mentality," says Iowa State University gerontologist Peter Martin. "You have to stay busy, so you have to be more disciplined, and finding ways to be busy and active is good for your body, good for your mind and good for longevity." Martin moved from Georgia to Iowa in part so he could study long-lived Upper Midwesterners.

Inez Blessum Thorstenson celebrated her 103rd birthday this past June. Thorstenson was born in Rugby in 1912—she still has vivid memories of the 1918 influenza pandemic. She has lived elsewhere in North Dakota and spent a brief stint in California, but most of her life has been in Rugby. Her parents lived into their 90s, and two of her brothers lived to be centenarians. "We have these Franciscan sisters in southern North Dakota who always live into their 90s and 100s," says Deb Hoffert, who does crafts with elderly patients like Thorstenson as a volunteer at Rugby's Heart of America Medical Center. "I don't know what's going on here. Maybe it's the prairie air?"

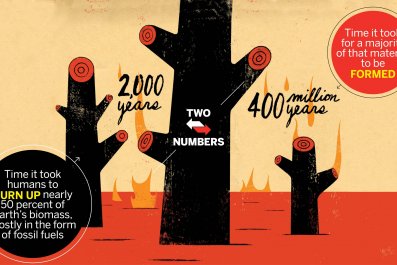

Oceans moderate temperatures, giving coastal towns milder winters and cooler summers. Areas far from the sea tend to be meteorologically extreme. North Dakota gets blistering heat waves—the state's hottest temperature, recorded in 1936, was 121 degrees—tornadoes and massive thunderstorms that can drop grapefruit-size hail. In winter, blizzards can last for days, and visibility can become so poor that you can't see your hand in front of your face. The state's coldest temperature, also recorded in 1936, was 60 below zero. When fronts pass though, temperatures here can rise or fall 80 degrees in a single day.

A study Martin published in 2012 in the Journal of Aging Research examined the lifestyles of 152 Iowa centenarians in rural towns to determine if certain traits seemed to favor long life. What he found is that strong community-support networks, resilience and active mental and social lives—combined with the extreme climate and geography of the Upper Midwest—all played a part. "Because you are more isolated and more rural, you are left to your own devices, and support becomes more important," says Martin. "If you are out in a snowstorm and get stuck, you need to have someone who helps you, and if people keep driving by, you aren't going to make it very long."

Another factor that may be contributing to the high percentage of centenarians on the Great Plains: People who can't take the extreme weather and isolation leave. "When the first pioneers came here, the people who thought it was too cold or harsh...didn't hang around too long," says Martin. "What you are left with are people with this survivorship characteristic."

Local artist Terry Jelsing was born in Rugby, bicycled to New Mexico to study fine art, attended the Institute for European Studies in Vienna and curated and directed the Plains Art Museum in Fargo, North Dakota. But he eventually realized that to find the inspiration his art required, he had to return to Rugby. "I kept looking for a place just like this," says Jelsing, 60, as he strolls the bucolic grounds of his 60-acre farm, trailed by a terrier named Sophie. "There is something neutral about nowhere, and because of that, it becomes unique and exotic."

On the farm is a 100-year-old red barn built with carved wood pegs instead of nails, in the old Norwegian style, as well as a series of gardens and a tomahawk-throwing course. North Dakota-inspired artwork dots the property. Jelsing's studio is a rehabbed granary, now occupied by his artwork and three cats. The studio sits on concrete piers, rising above the landscape like a boat. "In wintertime, it feels like you're sailing," says Jelsing. "Blizzards come, and you're snowed in for three days—snow swirling, obfuscating shadows and trees. You can't go anywhere, so you create your own world."

Jelsing's wife, Cathy, is a freelance journalist, and she says landing assignments in and around Rugby has been difficult. "If you're a professional of any kind, it's really hard to make a living in Rugby," she says. "You basically have to go outside." To make ends meet, she works as director of the town's Prairie Village Museum and plays viola in the town's 50-person symphony orchestra.

Across town, at the Heart of America Library, director Sheila Craun, a recent transplant from California, shares some of her discontents. "I miss the ocean!" she exclaims. "In Orange County, we spent the whole, entire summer going to the beach. My husband surfed and my son surfed, and we went to a dog beach just so our dog could come with us."

Craun and her husband moved here because it was cheaper, and to escape Southern California's crowds. Plus, her husband was offered a good job and had always wanted to live in the Midwest. (Their son stayed in California.) But she's still getting used to the culture. "People here are so entwined with each other's lives," says Craun. "They knock on your door, and you're like, 'Why?' In California, you come home and close your garage and close your door—no one talks to their neighbors."

Of course, as Martin found, those Midwestern manners may be one of the reasons the region is home to some of the country's oldest people. Take the example of someone who knows his neighbors' habits so well that he notices one night the lights didn't go off in a nearby home and calls to see if everything is all right. Craun and other Upper Midwestern newcomers might see this as prying. But Martin points out that for folks in their 90s and 100s, who might fail to shut off a light because they have fallen or need medical attention, this type of solicitousness can keep them alive longer.

Living in an environment with clean air and water is also key to a long life. And up until recently, these are things most North Dakotans took as a given. But the use of hydraulic fracturing (or fracking) and horizontal drilling to mine oil from the Bakken Formation that is layered deep below western North Dakota's surface has brought a boom to the state—it's now No. 2 in oil production, after Texas—and more than doubled the populations of some rural towns in the region. It's also begun to spoil the landscape and natural environment.

"There was a place out on the Badlands where I used to go to hunt mule deer," says Terry Jelsing, referring to a section of western North Dakota famous for its rugged red and yellow buttes, and smack in the middle of the Bakken boom. "I would stand there on this wonderful open space and hear absolutely nothing. Now it's an intersection."

Back at Lee's Bar, happy hour is coming to an end, and so is Ekren's shift. While the ocean is not on his agenda for the weekend, the water is. "When I get off work," he says, "I'm going to the lake."