Just before the end of Ramadan this year, I received an unexpected call from one of Mullah Mohammed Omar's longtime family friends. He had just learned a secret held by only a tiny circle of Omar's most trusted associates: The supreme leader of the Afghan Taliban was dead.

Rumors of Omar's death have been circulating since he vanished in late 2001. The last verifiable sighting placed him on the back of a Honda motorbike, heading into the mountains outside Kandahar while the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance fighters closed in on the city. But this caller was different—extraordinarily well placed to know about the Mullah's whereabouts. His claims were also very detailed. He asked not to be quoted by name on such a sensitive topic, but he and his family are highly respected for their longtime humanitarian work in Pakistan's Afghan exile community.

Omar died in Afghanistan, my contact says. People have often assumed that the Taliban leader fled across the border into Pakistan, like most of his surviving followers, but in fact he refused to leave his country of birth. If you're willing to trust the Pakistanis, you might just as well move to the United States, he told anyone who raised the thought.

Instead, he altered his appearance as best he could and tried to blend in among his countrymen. It helped that he had never permitted photographs of himself. After the Taliban regrouped as an insurgency, he began communicating with the leadership via a dedicated personal courier. Omar gathered a few loyal allies and even led them in occasional forays against the occupiers, the family friend says. He was wounded slightly a couple of times, but never seriously injured.

No one can be sure what killed Omar. Some have suggested it may have been a heart attack, but according to my caller he was a long way from any doctor who could have given a proper diagnosis when it happened in January 2013. The theory seems plausible; Omar would have been about 60 years old. His date of birth was never publicly disclosed, if he knew it himself. Longtime family friends say he was born on a roadside somewhere between Uruzgan province and Kandahar, where his desperately poor parents were headed in hope of finding work. For lack of better transportation, his mother was riding a donkey. When she went into labor, she dismounted; after the delivery, she climbed onto the animal's back, cradling the infant, and traveled on. She doubted he would survive.

Decades later, when the end finally came, Omar was holed up for the winter among the desolate mountains of Now Zad district in Helmand province, in an area of tiny villages known collectively as Taizeini. Few maps show the place, but it's roughly 100 miles northwest of Kandahar. A good friend was with him, according to my source. Mullah Abdul Jabar, a native of Zabul province, had served during the years of Taliban rule as governor of central Baghlan province. According to one of Jabar's relatives, he never went home again after 2001. Instead, he stayed faithfully by Omar's side as his messenger and attendant. The family friend says Jabar was the Taliban leader's only link to the Quetta Shura, the group's ruling council.

Omar told Jabar what to do in the event of his death or capture—get word to Mullah Sheikh Abdul Hakim. The religious scholar, a longtime friend and adviser of Omar's, makes his home in Quetta, the southwestern Pakistani city where the Taliban leadership resides. Hakim and Jabar quickly relayed the news to three other senior Taliban figures. One was Mullah Akhtar Mansoor, the head of the Quetta Shura. Another was Mullah Qayyum Zakir, director of the Taliban's military council at the time. And the third was another religious scholar and longtime Omar friend, Mullah Abdul Salam, who lives and preaches in the city of Kuchlak, a few miles outside Quetta. (None of the five could be reached for comment.)

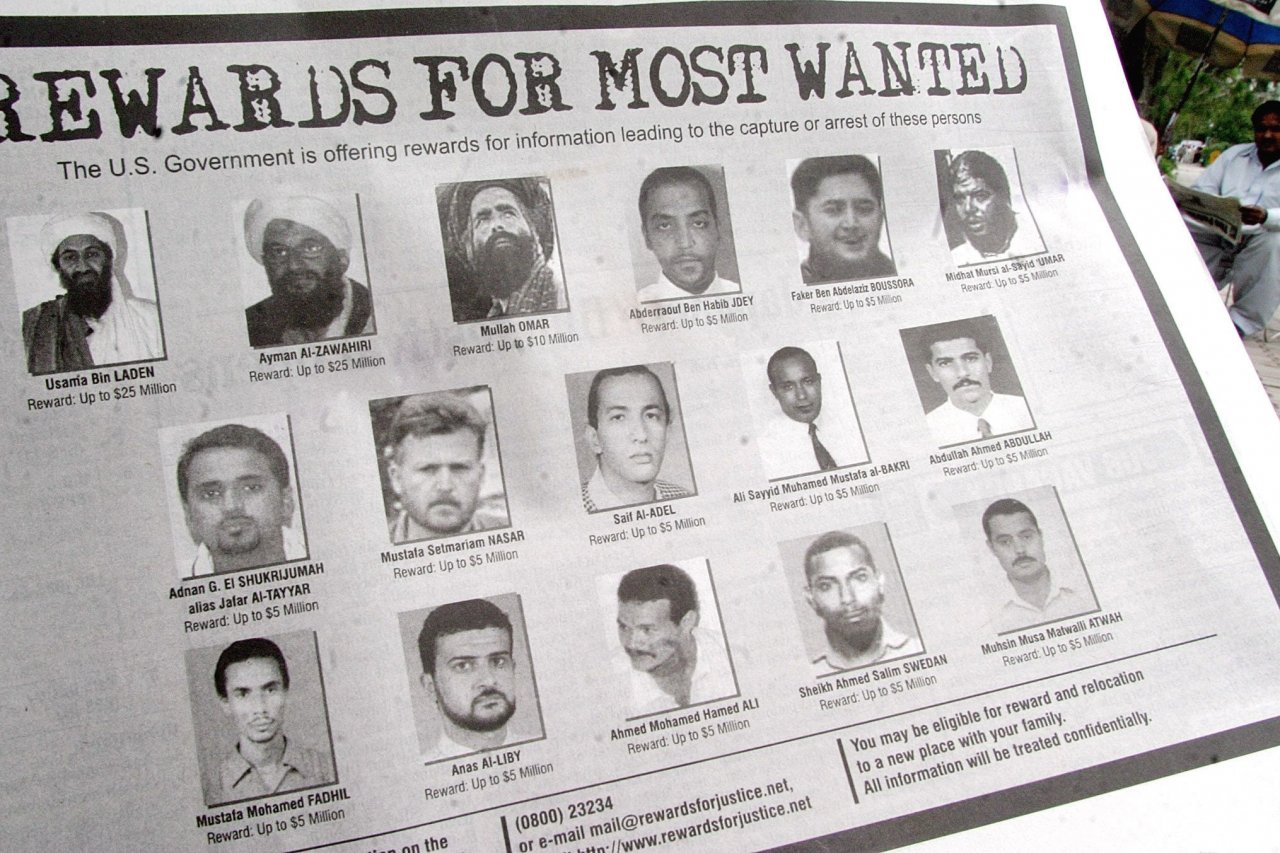

My source says he knows of only one other person who might have been told of Omar's death. (I couldn't reach him either.) Back in the 1980s, Mullah Gul Agha Akhund, another Quetta Shura member, fought alongside Omar against the Soviet occupation. In recent years, he has been widely described as the only member of the leadership in regular communication with Omar—and even he was never able to speak directly with his old comrade. One of Omar's wives and some of his children, placed under Pakistan's protection in Karachi and Peshawar, could never speak to the Taliban leader, for fear the U.S. might find out and somehow trace him. Secrecy was essential: The Americans had placed a bounty of $10 million on his head.

A week after Jabar brought his news to Quetta, the council chiefs Mansoor and Zakir held a private meeting with the two religious scholars. The family friend says Mullahs Salam and Hakim formally gave Omar's turban to Mansoor, appointing him to be Omar's successor as Amir-ul-Momineen—the "Commander of the Faithful." Sheikh Hakim gave him a grim congratulations: "You are now our leader. You must follow the path undertaken by Mullah Omar."

My caller says Zakir wanted to announce Omar's death immediately, but the others convinced him not to talk. In order to keep it secret, the Quetta Shura went so far as to issue a decree prohibiting any questions about Omar's fate. Violators would be referred to a Taliban court.

The war was at a critical juncture: President Barack Obama had just announced plans to begin a drawdown of U.S. combat forces in Afghanistan. But while the Taliban waited for a pullout, Omar's death created huge problems for Mansoor. The one thing that kept the Taliban united was his fighters' absolute devotion to their founder and spiritual leader.

Now the group's new emir was left to wind down the Taliban's unwieldy war machine. Many of his fighters had no recollection of a world without Mullah Omar—let alone any memories of an Afghanistan at peace. Mansoor needed to give them time to adjust. In June 2013, less than six months after he's said to have received Omar's turban, the Taliban finally opened its long-awaited political office in Qatar and began talking with the Americans. The talks broke down almost immediately.

While the military chief kept his mouth shut, he remained distraught about Omar's loss, my source says. In April 2014, Zakir finally stepped down from his post, pleading ill health and overwork. At the time, Taliban officials told me the famously hawkish military chief and Mansoor had been arguing for months about the ruling council leader's desire to make peace. But now Omar's family friend says Zakir was simply too depressed to go on. He said he no longer wanted any official post in the leadership: "Without Mullah Omar, I hate everything."

When the caller hung up, I began dialing my best Taliban sources and sending emails to check out the story. Preparations for the traditional end of Ramadan festivities made many of my best Taliban sources hard to reach, but I kept trying. Coincidentally or otherwise, the family friend had contacted me on July 15—the same day the Taliban chose to publish this year's Eid al-Fitr greeting to the faithful. It was signed by Mullah Omar himself, as it has been every year. Some of my Taliban contacts insisted that Omar was not dead and would soon prove it publicly. Others pled ignorance. But no one bothered to pretend this year's Eid message had anything to do with whether Omar is dead or alive. For years, his longtime followers have quietly conceded that his signed statements are far too polished to have been composed by the Taliban's inarticulate and barely literate founder.

Nevertheless, confirmation of Omar's death was hard to find. Even before the Quetta Shura imposed its ban on questions about his health, it was a dangerous topic among the Taliban. "It bears a stink of disloyalty if anyone asks about his medical condition or what he's been doing," a Haqqani Network commander tells me. "We don't need to put him in danger by calling for definite proof that he's alive," a former Taliban fighter says.

A second report of Omar's death hit the Internet a week after the call from his family friend. This one was issued by a source not so sympathetic to the Taliban leadership: a tiny but bloodthirsty splinter faction that uses the name Fidai Mahaz—"the Suicide Front." The group quit the mainstream Taliban in 2013 in open rebellion against Mansoor's willingness to engage in peace talks.

Late last week, on July 22, the group's website published a sensational accusation that Omar had been "martyred" by his old associates Akhtar Mansoor and Gul Agha. According to Fidai Mahaz, Omar's death resulted from a violent quarrel the pair had with Omar, who objected to the recent opening of talks with the Americans in Qatar. As if that wasn't shocking enough, Fidai Mahaz claimed the alleged killing took place in July 2013—during the holy month of Ramadan. The group says the burial took place in Zabul province. Proof will come, the group promised. After the claim was posted, I contacted Mullah Najibullah, the leader of Fidai Mahaz. He tells me that further details will be released when the time is right.

The group's allegation echoed across Twitter, Facebook and other social media sites for another week. Then, on Wednesday, July 29, Afghanistan's intelligence agency joined the fray. Abdul Haseeb Sidiqi, a spokesman for the country's National Directorate of Security, told reporters from a roster of leading news services that Omar was definitely dead. The Taliban leader "died suspiciously in a hospital in Karachi around April 2013," Sediqi told The Wall Street Journal. Another Afghan intelligence official told The New York Times that Omar had been "suffering from a disease," and added: "We do not know the whereabouts of his graveyard or whether he received a ceremony."

Omar's family friend stands by his version. The Mullah died in January 2013, he says, in Helmand province. His burial took place in the same village where his life ended, in Now Zad district. Only three or four people attended the funeral rites. It was the only way to keep his death a secret.

Despite the almost farcical conflicts among the various accounts, they all agree on just one point: Omar is dead. The Quetta Shura is expected to issue a formal announcement soon. Meanwhile, everyone else is trying to predict what will happen next. Will the Taliban's representatives even show up for the next round of peace talks on July 31? Will the insurgency's ranks shrink as its fighters hear that their spiritual leader is gone? Will the hardline jihadis of the self-styled Islamic State gain a wave of new Afghan recruits? Can the Kabul government avoid a collapse into factions and civil war, as happened in the early 1980s after the Soviet pullout?

It may very well be the case that Afghanistan needs Mullah Omar now more than ever.

With Sam Seibert in New York.

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly said that Mullah Omar's family friend claims the Taliban leader died in 2012. He claims the Mullah died in 2013.