Ever since Steve Austin displayed his bionic powers on The Six Million Dollar Man, we've been talking about adding body parts that make us superhuman. These days, the most likely body part to get upgraded by mass-market technology is our ears. Our eyes lost out when Google Glass proved to be about as useful as a Segway, and almost as embarrassing to own.

Compared with boosters for legs, hands, noses or anything else, augmented hearing is the closest to becoming accessible and common. This could first change the nature of live music and later affect much bigger things, like cities, language and relationships. Just wait until you can tune out your spouse with augmented hearing earbuds—like hitting mute when Donald Trump comes on TV—and set your audio world so all you hear is the doorbell. (Because you won't want to miss the pizza delivery.)

And who knows what will happen once we can hear colors? (Maybe it will cut into the psilocybin mushroom business.)

Before the end of the year, startup Doppler Labs plans to come out with a promising product called Here—oversized earbuds, about the size of a quarter, meant to give you control over live sounds. They don't play Spotify songs; instead, they filter and alter the thrum of the real world around you. The early versions will have volume control and some noise cancellation, so you can put them in your ears and make city sounds less harsh while boosting conversations so they come through loud and clear. One Here setting is "Baby Suppress," which sounds like birth control but is meant to squash the sound of the crying kid behind you on a cross-country flight.

For an aging population that grew up damaging their cochlea at Ramones concerts, augmented hearing buds could do some of the work of hearing aids while feeling cooler to wear and costing one-tenth as much. The first Here buds will be less than $300; hearing aids go for anywhere between $2,000 and $7,000.

Doppler is initially aiming Here at lovers of live music. CEO Noah Kraft, a musician and audiophile, found it frustrating that the music sounded different in various areas of a live venue. Here buds will allow a user to adjust volume, bass and effects such as reverb to customize a concert's sound. Before long, Kraft says, the band's sound chief could send settings to every Here bud in the room so everyone wearing them has the same optimized experience.

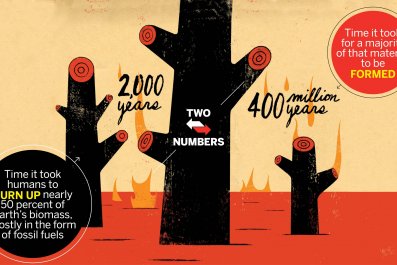

Augmented hearing buds could be the biggest thing to hit live music since electric amplification, which changed the very nature of music, from orchestras and big bands to small combos playing through microphones and amps. Once everyone in a venue is wearing augmented ears, artists will be able to rethink the way the music gets to our brains. Maybe every member of the band will play in a different corner of the room, allowing audience members to wander from one musician to the other, seeing the performance intimately while still hearing the sound all perfectly mixed together.

"Our hope is that Here will open up a new paradigm for the concert experience and for live listening," Kraft told Rolling Stone.

But Doppler and others working on augmented hearing don't plan to stop at music. Doppler has a vision for "a computer, speaker and microphone in every ear"—a nod to Microsoft's old goal of a computer on every desk—and predicts that in 10 years people will wear these 24 hours a day. The company's grand plan includes mapping every point on Earth for sound, so your buds could automatically optimize what you hear. Imagine these buds with GPS, knowing that if you're home at 2 a.m., it should adjust to cancel the snoring next to you and the neighbor's barking dog. Or if you're on a hike in the backwoods, it should amplify any distant sounds of a bear charging your way.

Augmented hearing could change the economics of a major city, where noise has an impact on where people choose to live and work. Heck, if you could wear noise-canceling buds all the time, you could live under a jet runway approach that's next to a bus depot.

While Doppler seems furthest along, it's not alone in chasing these ideas. You can already buy sound-augmenting apps that use your smartphone as the mic and filter, pushing the altered sounds to your regular earbuds or headphones. Ear Spy, for instance, markets its app as "the latest in personal espionage," letting you tune in a conversation from across the room. A group of Finnish researchers recently published a study on what they call the "pseudo-acoustic environment," which they describe as "a modified representation of the real acoustic environment around a user." And high-end hearing aid makers have continually built more acoustic filtering into their devices. GN ReSound Linx has a mode meant for restaurants that turns down music and background noise and focuses on conversation. Such hearing aids, though, cost thousands of dollars and are marketed as medical products, not consumer gadgets.

One brilliant aspect of augmented ears is that a huge chunk of the population already wears things in their ears a good deal of the time. Earbuds don't draw attention or announce that you're a geek. They don't creep out people around you. And an aging but still vain demographic that needs help hearing but won't wear a "hearing aid" (estimates are that only one-fifth of people who need hearing aids use one) would more likely sport cool new earbuds that do much of the same work. "The ear is such a logical place [for a device] because we've been wearing wearable tech on our ears since the Walkman," Doppler Executive Chairman Fritz Lanman told Wired.

Beyond Doppler's vision, some of the propositions for augmented hearing get pretty wild. Once you have a computer in your ear, it could do a lot of things your ears could never do. One idea is instant translation. Automated language translation is getting better all the time. Combine that with a sound processor and it could catch Chinese coming in and send English into your ears. Language barriers would disappear—and with them, maybe any need to teach foreign languages.

Another idea is to allow us to hear wavelengths never meant for our ears. Color is a wavelength we see but can't hear, but what if you could hear green? Imagine the impact on the colorblind. Or what if you could hear infrared, essentially letting you see in the dark through your ears?

This stuff is likely to happen. With Google Glass and the stalled Apple Watch and other wearables, there's no there there. Now, however, we'll soon have a Here here.