On a clear day in June, a crowd gathered along the banks of the Tioga Mine Pit Lake to watch the Itasca County Sheriff's Office strap into scuba gear and dive for sunken treasure. It was the latest attempt in the decade-long search for a pair of ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz that had disappeared from the Judy Garland Museum in Grand Rapids, Minnesota. Judy Garland likely wore the pair in the movie; three other surviving on-screen pairs are known in existence. Rumor was that whoever stole the shoes got nervous and chucked them into the lake, which drops 225 feet. A 2005 insurance policy valued the shoes at $1 million, but one appraiser now says if found in good condition, they could fetch at least twice that.

The dive failed to turn up the sequined pumps, but the case stayed hot. After hearing about the dive, an anonymous benefactor telephoned the museum and offered to finance a $1 million reward for locating Dorothy's shoes. The news of the added incentive traveled fast, ending up in the pages of The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian and Us Weekly. Wuollet Bakery in Minneapolis began selling cakes depicting the slippers and "REWARD: $1,000,000" written in icing. Marriott also announced a reward, independently of the museum, for whoever can locate the slippers by August 31—1 million Marriott Reward Points, worth $12,500.

After only a few weeks on the table, the $1 million offer expires August 27, the 10-year anniversary of the theft.

Since 2005, the case of the stolen slippers has put a spotlight on Grand Rapids, a timber town of 11,000 residents and the birthplace of Judy Garland. Locals are "decent, hardworking people," says investigator Andy Morgan of the town police, who inherited the case about six years ago. "Everybody was aware of the theft. It was top news, not only locally but far outside of locally."

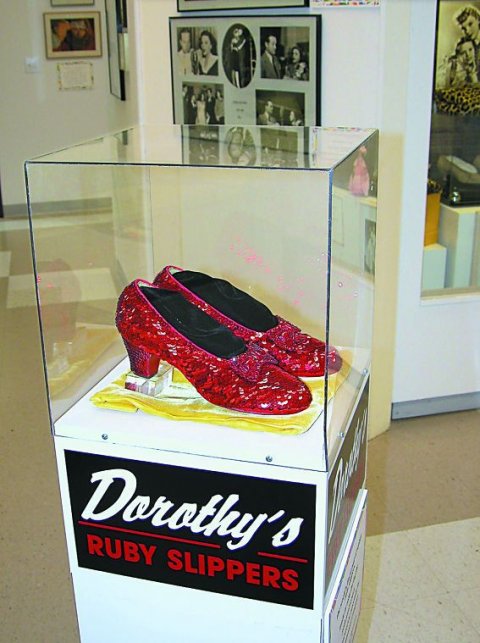

Shortly after 2 a.m. on August 28, 2005, a thief (or thieves) smashed a window in the museum's back door and entered. They approached a Plexiglas case resting on a podium that contained the slippers, smashed the top, grabbed the shoes and fled the way they came in. They took nothing else and left behind no fingerprints or clues—only a trail of broken glass from the door to the case and a single red sequin. Dorothy's slippers had slipped away.

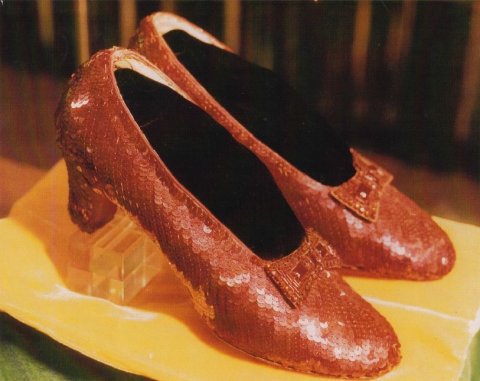

The size 5.5 slippers, in good condition and hand-labeled "Judy Garland" inside, belonged to Michael Shaw, a southern California-based collector whose haul includes the tablets and golden calf from Cecil B. DeMille's 1956 Moses epic, The Ten Commandments. Five or so times, he had rented the shoes to the Judy Garland Museum for the summer, charging the museum a few thousand bucks. The theft happened a week before Shaw was to come collect them.

"I literally felt like I was hit in the stomach when I got the call," Shaw says. "My knees buckled, and I went right down on the floor. I had taken care of those shoes for 35 years!"

The museum folks were devastated too. "I cried," says Jon Miner, the museum treasurer and co-founder. "I couldn't believe this happened to us because it was the stupidest thing."

The museum had an alarm system and video surveillance, but neither was operating at the time of the theft—a detail that would raise suspicions that the theft was an inside job. Other people speculated that Shaw had paid someone to steal the shoes—perhaps replicas—so that he could collect insurance. Kyp Alexander, a private investigator who worked on the case, says, "There's a lot of theories surrounding this. You could say there's as many as Area 51 had, as far as conspiracies or theories."

Four months after the heist, Essex Insurance Company took Shaw, the museum and its director to court before shelling out $1 million. The company claimed the museum had voided its insurance policy by not disclosing changes to its security measures. The parties settled in 2007 and Shaw received $800,000.

"The insurance company, they investigated me upside down, inside out," Shaw says. "They realized I had nothing to do with it. And basically the museum knew it too. They were reaching at straws to try to throw the guilt away from themselves."

While Shaw and the museum played the blame game, police and private investigators continued the hunt. "Tons of attention and resources were given to chase down any leads," Morgan says. Tips came in from all over; Miner estimates they received 1,000 calls. People said they spotted the slippers at a garage sale in Virginia and stapled to a restaurant wall in Missouri. A radio station was apparently giving them away in New Hampshire.

One tip brought the search to San Diego in 2011. A man had reported a home burglary, and when law enforcement visited him, an investigator noticed he had ruby slippers. The man said he had received them from a former lover. The investigator got a search warrant, but upon closer examination, serial numbers and other details didn't match Shaw's pair. Those slippers were likely fakes.

At one point, Essex Insurance reportedly offered $200,000 to whomever could find the slippers, and a museum board member kicked in an additional $50,000. But by the time Morgan took over the case around 2009, the leads had dried up. "I don't want to say it became less of a priority," he says, "but with it being handed down, and no new information coming in, the file just continued to sit."

The Start of the Yellow Brick Road

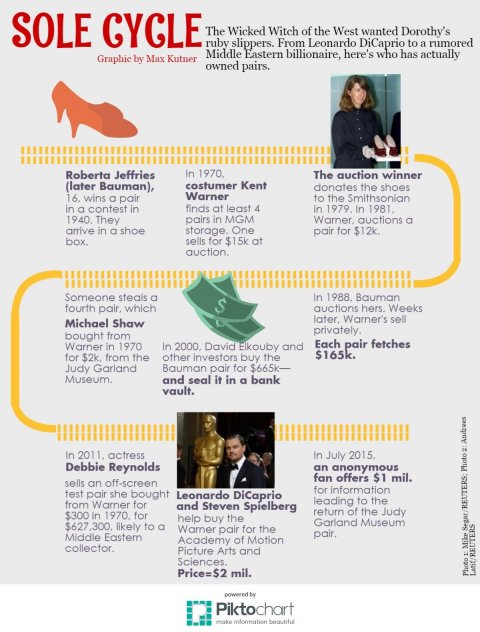

Memorabilia experts say they don't understand how an item as significant as Shaw's ruby slippers could vanish without a trace. But the story of the slippers began that way. Film historians have said that in 1939, when MGM released The Wizard of Oz, studios didn't think twice about preserving costumes. It wasn't until 1970 that costumer Kent Warner discovered several pairs of authentic ruby slippers in storage on the MGM lot. (It was common practice to make multiple sets of costumes.) He sold one pair to Shaw for $2,000 cash, along with Dorothy's dress, the witch's hat, a Munchkin outfit and a gown from 1938's Marie Antoinette. Warner also sold a test pair, not worn in the movie, to actress Debbie Reynolds for a reported $300. Warner gave an additional pair to an auctioneer and kept a final pair for himself (though he told the auctioneer that pair was the only one).

According to accounts, the pair of ruby slippers was the highlight of that 1970 auction, which took place on the same soundstage where MGM had filmed The Wizard of Oz. The slippers sold for $15,000, the most expensive costume item in the multiday auction. But days later, a Memphis woman told reporters she too had a pair of authentic ruby slippers, which she had won as a contest prize in 1940. With that revelation, the public realized multiple pairs existed. Four on-screen pairs and one off-screen test pair have surfaced, and collectors have paid more and more to get their hands on them.

Rhys Thomas, author of the 1989 book The Ruby Slippers of Oz, has spent decades tracing the histories of each pair. The person who bought the auction slippers donated them to the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in 1979. Dwight Blocker Bowers, a Smithsonian curator, says they keep the pair in a locked, alarmed case, under 24-hour guard surveillance. "Any kind of tampering with the case would immediately send a message to the guards' office," he says.

The Memphis woman sold her pair in a 1988 auction to a collector for $165,000. That collector loaned them for display at Disney World, before selling them at auction in 2000 for $666,000 to a group of collectors and investors. One of them, David Elkouby, tells Newsweek they keep the shoes in a bank vault. "We were collectors, and for us, that's the ultimate prize."

Warner sold his slippers in 1981, three years before he died of complications related to AIDS. They went for only around $12,000. But a few years later, in 1988, that anonymous buyer sold them to a collector for $165,000. In 2012, that collector sold them for $2 million to a group purchasing them for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which included Leonardo DiCaprio and Steven Spielberg.

Reynolds auctioned off her pair in 2011 for $627,300. Called the Arabian Test Pair, it has a different design, with beads over the sequins and curled toes; Judy Garland wore the pair only in screen tests. Two memorabilia experts believe the buyer is from the Middle East, where collectors have in recent years spent more and more money to acquire art.

Unless Shaw's pair resurfaces, only Elkouby's is likely ever to return to market. "The Smithsonian is never going to sell their pair, so that's locked up, and I can't imagine the Academy will ever sell this pair now," says Laura Woolley, an appraiser who has appeared on Antiques Roadshow and has appraised authentic ruby slippers. "What it really means to me is that last private pair, the value of that one has grown exponentially."

Woolley suspects that if found intact, Shaw's slippers could sell for even more than the $2 million pair, thanks to the added publicity around the theft. But if they're destroyed, she says, "they become kind of a grave marker for what happens when you don't properly guard against thievery in this world. I think for far too long people have taken this area of collecting far too casually."

No Place Like Home

"The shoes themselves are worthless," Michael Shaw told Rhys Thomas, the author, decades ago. "It's what they are and what they represent."

At the Judy Garland Museum today, the empty podium still stands, not that anyone needs a reminder of what happened. There's bad blood between just about everyone involved: the private investigators and the police, the museum and Shaw, Shaw and Rhys Thomas. Misinformation is rampant, and everyone is skeptical of everyone else's motives.

"There's a lot of distrust and distaste left in their mouths, for sure," Kyp Alexander, the private investigator, says of Shaw, the museum and the police.

The latest person (or people) to join the saga is the anonymous benefactor who has offered $1 million for the slippers' safe return. Museum officials say the benefactor is a wealthy family that is "a friend of the museum" and has connections to Grand Rapids, Judy Garland and The Wizard of Oz. The benefactor initially agreed to a phone interview with Newsweek, which the museum coordinated, but then got cold feet and reneged, the museum says.

Rhys Thomas, among several others, is skeptical such a benefactor exists. He says he believes the museum is only trying to drum up interest for its imminent sale of another piece of Wizard of Oz memorabilia, a horse-drawn carriage from the movie that supposedly Abraham Lincoln once owned. (Miner, the Judy Garland Museum treasurer, mentioned that item several times in an interview, as did a museum spokesman.) However, the museum offered to provide Newsweek with a notarized letter from benefactor's attorney confirming his or her or their existence.

Thomas says the world of ruby slippers is a rabbit hole as full of whimsical—and perhaps wicked—characters as Oz. "They're an object of intense obsession," he says. "The ruby slippers just command so much interest and overpower the individual who owns them."

"Everybody's a little nuts, but they're nuts for a really good reason," says Morgan White, who is working on a documentary, The Slippers. "They are the kings of collecting. They got to own the thing that everyone wants."

Compared with collecting art, says Woolley, the appraiser, "there's a much deeper emotional connection [with memorabilia]. Most people encounter these objects or develop a fondness for them in childhood. And when you grow up and suddenly you're an adult with money to spend, you can recapture something from youth," she says. "Most of these things kind of turn people back into children."

People who have followed the case say one theory has endured over the years—that local teens stole the shoes as a prank, got scared and ditched them. "People know who did it, but they're just not talking," says Theodore James, another documentary filmmaker, whose film Who Stole The Ruby Slippers? premiered at AFI Docs in Washington, D.C., this summer.

White agrees. "All signs seem to point to the fact that these kids did it," he says. "They're probably sitting at the bottom of the mine pit and nobody will ever see them again."

Thanks to the publicity surrounding the $1 million reward, tips have started coming in again, Miner says. "After time goes by, people are a little loose with their tongue, so we're hearing things that we never heard for the last 10 years."

Still, police say the statute of limitations has run out, and some people are skeptical that the sleepy museum and local law enforcement have a clue how to handle a heist that Woolley compares to the one at Boston's Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, where Rembrandts and other masterworks were stolen in 1990.

"It's a multimillion-dollar art theft. They don't think of it like that," White says, referring to the museum and police. "They thought that it would go away, and it didn't go away." The shoes are not listed in the FBI's art crime database.

If the slippers do reappear, they will belong to the insurance company. Shaw, who turns 78 next month, sounds at peace with that. "There's more to my life than a pair of pumps," he says. "I have no desire to have them again. After years of bringing joy and happiness to so many thousands and thousands of people by being able to see them, now to me they're a nightmare."

He ends a phone call with Newsweek by saying, "I'm not going to talk about it anymore. I'm sick of it. They're gone." Then he quotes another Hollywood classic: "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn."