Days after taking a hard hit to the head during a boating accident, 24-year-old Brianne Cassidy had a life-threatening stroke. By the time she was admitted to the hospital, she was unable to speak or use the right side of her body.

When tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment to dissolve the clot that had caused the stroke failed, doctors took a different approach: removing the clot with the help of a special stent called a "stent retriever" or "stentriever." Cassidy's response to the procedure was dramatic. Within minutes, she was able to move her right arm and leg, and her speech had improved. Within weeks, Cassidy says, she was "back to normal."

Stroke is the fifth-leading cause of death and the leading cause of adult disability in the U.S. Like Cassidy's, most strokes occur when blood flow to the brain is blocked by a blood clot. Deprived of oxygen, brain cells begin to die within minutes, often causing immediate loss of function elsewhere in the body.

Since its FDA approval in 1996, tPA has been the treatment of choice for most of the 800,000 people each year who suffer clot-induced, or ischemic, strokes. But tPA is effective only when given within 4.5 hours of when stroke symptoms set in. And even then, says Dr. Gregory Albers, a vascular neurologist at the Stanford Stroke Center in Palo Alto, California, "it only works in about a quarter to a third of all patients."

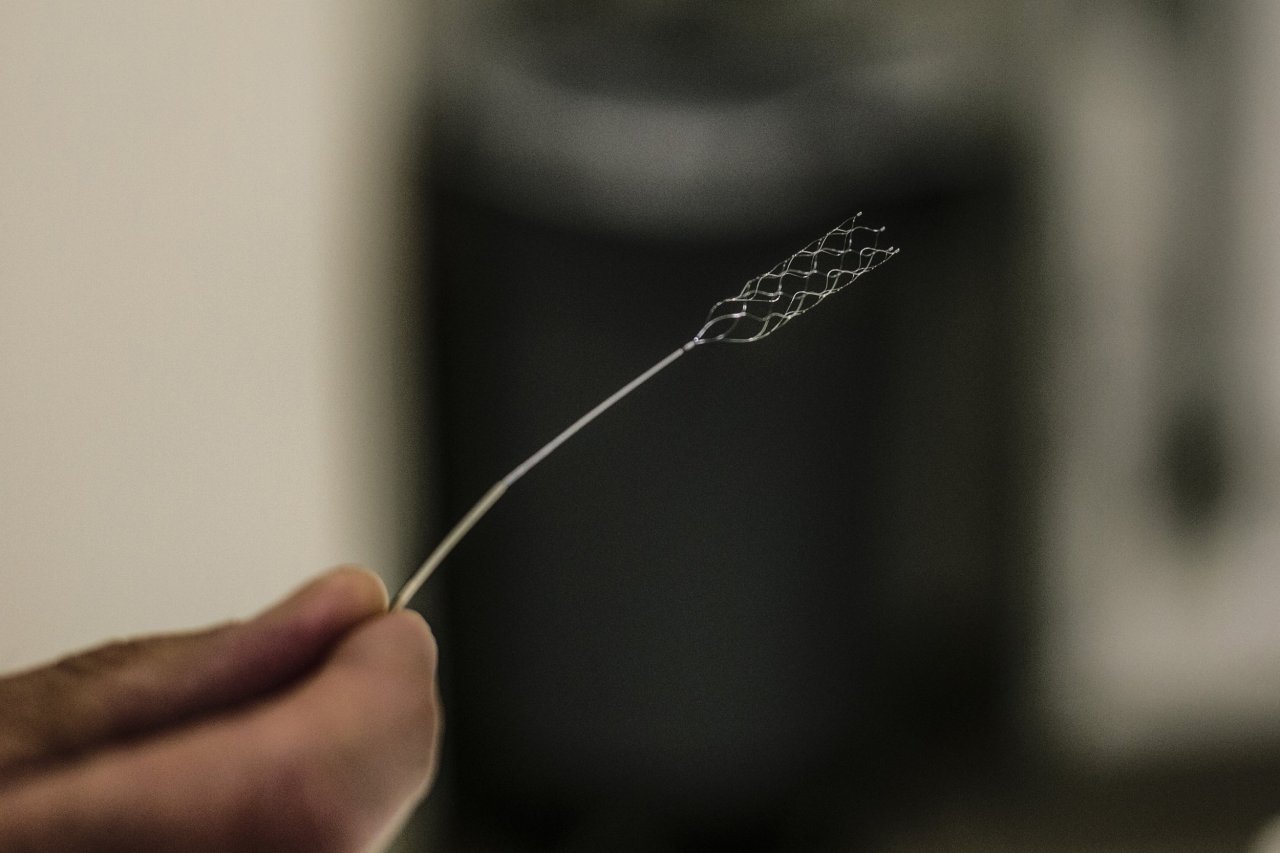

Resembling a tiny wire cage, the stent retriever is threaded through a catheter into a blood vessel in the groin, then guided up to the blocked artery in the brain. The cage then opens up and captures the clot. Then the stent, along with the clot, is removed, immediately allowing blood to begin flowing again to the brain.

In July, the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association issued guidelines recommending the use of the stent retriever in concert with tPA after five studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine within the past year found that stent retrievers reduced disability, improved neurological function, shortened recovery time, and increased the rate at which stroke survivors regain function. The guidelines call for use of a stent retriever (either Medtronic's Solitaire or Stryker's Trevo ProVue) when an adult patient can be treated within six hours of the onset of stroke symptoms, has a clot in a large artery that feeds the brain and has had brain imaging that shows the brain is not already permanently damaged.

Though the devices are available at more than 1,000 stroke centers and hospitals in the U.S., only about 13,000 procedures are performed annually—mostly at comprehensive stroke centers—because they require specialized training. Albers says two or three stroke patients are treated each month at Stanford with a stent retriever device, but adds that the number will likely grow with the issuance of the new guidelines, which he calls a "landmark change" in stroke care. It's the first time the groups have recommended a device for treating strokes and the first time in two decades the group has issued a Class 1, Level of Evidence A recommendation—its strongest possible endorsement.

Follow Aimee Swartz on Twitter at @swartzgirl