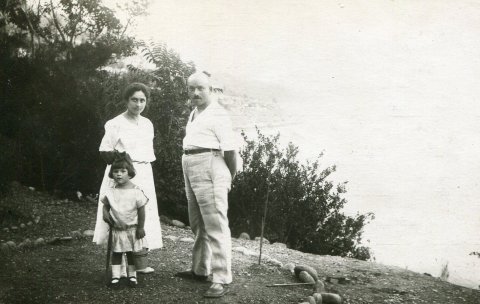

The secret police came for Boris Shternberg on the night of October 17, 1937, at the height of Soviet tyrant Joseph Stalin's purges, arresting him in his central Moscow apartment in front of his terrified wife and teenage daughter. For the next two months, they tortured the 51-year-old civil servant into confessing to a host of false charges, including the poisoning of the city's water supply.

His torment over, Shternberg was then shot dead, most likely with a single bullet to the back of the head, and his body dumped in a mass burial site near Moscow, according to documents later obtained by his family. Under the Soviet system of collective punishment for "enemies of the people," his family was evicted from their home, and all their possessions were confiscated. His wife was sent to a corrective labor camp for five years.

Almost eight decades on from Shternberg's murder, his granddaughter, Nina Kossman, a dark-haired woman in her early 50s, waits in the street outside the seven-story residential building where her grandfather spent the last years of his life. In her hands, she holds a gray plaque made of galvanized steel that states, with lines etched in stark black lettering, the grim details of Shternberg's life, arrest and execution. The final line gives the year, 1955, that Shternberg was finally cleared of all the charges against him. To the left of the text, in place of a photograph, is a square-shaped hole.

Kossman, a Russian-born writer and translator who lives in New York, says her grandmother trusted in Communism and always thought her husband's execution was a terrible mistake. When she was growing up, the purges were barely spoken of in the family. "This is a real thing that happened to millions of people, and it has to be brought out into the open," she says.

Shternberg's case was far from unique. In just the half-mile-long street where he lived until his death, 60 people were taken from their homes and murdered by Stalin's executioners between 1937 and 1938, when the killings reached a peak. There was little apparent logic to the arrests. Among the victims were ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Latvians and Estonians, as well as two Poles. Some, but by no means all, were Jewish. They were engineers, academics, students, teachers, military men, architects. One was a publisher of children's books. In Moscow alone, during this same period, the NKVD, the secret police agency that would later become the KGB, shot some 30,000 people, according to Memorial, Russia's oldest human rights organization. Many others were arrested and later died in the gulag system of labor camps. There is no commonly accepted figure for the total number of people who died as a result of Stalin's policies across the Soviet Union, with estimates ranging from just over 1 million to as high as 60 million.

While an abundance of commemorative plaques honor Soviet military men and party officials in the fashionable Moscow district where Shternberg lived, the bloody history of these homes is unknown to the majority of Russians, including those who now reside behind their walls. While Memorial is permitted to hold an annual gathering in Moscow to remember those murdered by the Soviet authorities, President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly declined to offer an unequivocal condemnation of Stalin's three-decade rule.

"Moscow is a city soaked in terror," says Arseny Roginsky, Memorial's long-serving director. "But while everyone knows that lots of people died during the Stalin era, they are largely thought of as almost accidental victims, as if they were wiped out by some medieval-type plague, for which no one can be held responsible. They don't fully comprehend that this was a deliberate crime by the state against its own people."

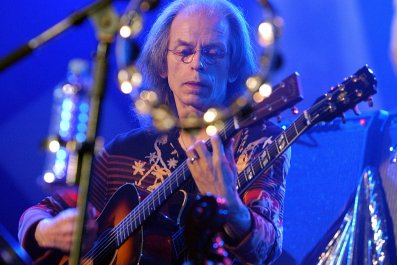

That's where Sergei Parkhomenko, a veteran Russian journalist and civic rights campaigner, comes in. Last year, inspired by German artist Gunter Demnig's "stumbling blocks"—tiny commemorative brass plaques installed on the sidewalk outside the final address of victims of Nazism—Parkhomenko launched last year a crowdfunded project called Last Address. The concept is very simple. A website (Poslednyadres.ru) allows Russians to apply to have a memorial plaque installed in honor of a family member or friend murdered by the Soviet state at their last voluntary place of residence. Once they have the current residents' consent, they pay around $60, and a plaque is produced by a craftsman. To date, there are around 80 of these commemorative signs across Moscow, with another 10 in other cities. "We've had around 900 applications from all over Russia," Parkhomenko says, as he reaches for a power drill to mount the plaque in memory of Shternberg. "But it's slow work."

Honoring Stalin's innocent victims might seem like an uncontroversial activity, but Parkhomenko has been unable to obtain official blessing for his project. "Initially, we had long negotiations with the authorities, and everything seemed to be going well. But after [the invasion of] Crimea, they stopped speaking to us," he says. "At the moment, we have an unspoken agreement—we don't ask for permission, and they don't stop us. It's anyone's guess how long this will last, though."

The project has provoked fury among nationalists. "This is not only unnecessary, it is also harmful. It is a dangerous distraction from the task of strengthening our homeland," says Alexander Prokhanov, a Kremlin-connected writer who was allied to those behind the unsuccessful 1991 coup attempt by Soviet hard-liners angry at Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms. "These people are trying to hinder Russia's development."

In Germany, the use of Nazi symbols, including images of Adolf Hitler, is banned, but Stalin is an all-too-common face in modern-day Russia. On May 9, during Russia's celebration of the 70th anniversary of victory in World War II, the Soviet dictator seemed to be everywhere: War veterans carried portraits bearing his unmistakable image through Red Square, while state television screened documentaries hailing his achievements as supreme commander in chief of the Red Army. Among the souvenirs on sale to tourists in Moscow are Stalin T-shirts, cups and decorative dishes. "He was a hero and a great man," the guide at a Stalin museum in Volgograd, formerly known as Stalingrad, told Newsweek earlier this year, as she stood next to a life-size wax figure of the diminutive generalissimo.

It's not only images of Stalin that are gaining popularity. Amid a spiraling confrontation with the West over the conflict in Ukraine, the language of Stalinist terror has made a startling return to Russian political life. Putin has labeled Kremlin critics "national traitors" and a "fifth column." Less than a week before opposition leader Boris Nemtsov was gunned down near Red Square, participants at a state-sanctioned march in central Moscow called openly for the "destruction" of the government's opponents. And then there are the increasingly frequent show trials. In late August, Ukrainian film director Oleg Sentsov was jailed for 20 years on terrorism charges that were widely seen as both revenge for his involvement in protests against Russia's seizure of Crimea and a warning to others not to challenge Putin's authority. In a display of legal nihilism that shocked even experienced human rights workers, a military court in southern Russia dismissed Sentsov's claims that he had been tortured by Russian security forces, ruling instead that his injuries were the result of passionate sadomasochistic sex sessions before his arrest. And public attitudes toward state terror appear to be shifting rapidly: A public opinion survey published earlier this year by the independent Moscow-based Levada Center pollster indicated that 45 percent of Russians believe the killing of millions of people during Stalin's purges can be justified by "historical necessity." That figure has almost doubled since 2013.

In this context, says Parkhomenko, the Last Address commemorative plaques take on a far greater significance than mere memorials. "We want children to see them and ask their parents about them. And for people to explain," he says. "Russia is heading once more towards totalitarian terror. The aggressive nationalism that we are seeing now leads directly to the idea that the individual's life is worth nothing, and that only the state's interests are important. The Last Address project stands in direct opposition to this. We say that there is nothing more important than human life."