Updated | Miriam Szychowska has been hanging decorations on the wall, stocking books to read and preparing songs to sing in readiness for when 10 children stepped into their new preschool classroom on Tuesday. But unlike in other classrooms around Lodz, one of the largest cities in Poland, the colorful drawings that cheer up the space depict boys wearing yarmulkes, and the videos the children will watch once a week feature cartoon versions of figures from the Tanakh, the sacred Jewish text also referred to as the Hebrew Bible.

Szychowska's brainchild, Gan Matanel, became the city's first full-time Jewish educational institution in nearly half a century when it opened its doors on September 1 to a small group of students ranging in age from 1.5 to 4.5 years, according to the nonprofit organization Shavei Israel, which aims to help descendants of Jews connect with their roots and with Israel. Szychowska's husband, David Szychowski, is Shavei Israel's new emissary just dispatched to Lodz, and the organization says it will contribute funding for the preschool's operations.

"Opening the gan was obvious," Szychowska tells Newsweek on the phone from her new home in Lodz, using the Hebrew term for a preschool or kindergarten (the word also means "garden," as in Gan Eden). She says that before now, there was no Jewish education in the city other than the Sunday school run by the Jewish Community of Lodz, which organizes lectures, religious and cultural events in the city. That simply wasn't enough, she says. "I need this for my children, for other children."

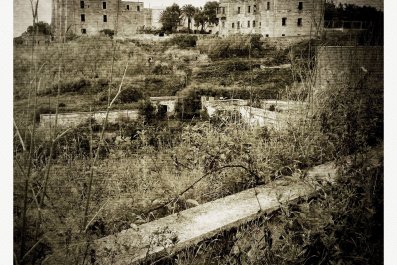

Though Lodz had a Jewish population of more than 200,000 on the eve of World War II, its Jewish community, led by Rabbi Simcha Keller, now numbers less than 400. During the first months of the war, about 75,000 Jews left Lodz, and approximately twice as many were recorded in the city's ghetto in June 1940, soon to be joined by more Jews deported from other Nazi-occupied territories, according to the YIVO Encyclopedia. Tens of thousands of Jews died in the Lodz ghetto, and more were deported to Chelmno, Auschwitz-Birkenau and labor camps. When the advancing Soviet army arrived in January of 1945, there were fewer than 900 living Jews in the city. Poland overall saw roughly 3 million Jews, or 90 percent of its Jewish population, perish in the Holocaust.

Lodz once again drew Jews after liberation, but not for long. Many emigrated in the first years after the war, and the community continued diminishing under Communist rule, until the anti-Zionist purges in the late 1960s put an end to most Jewish activity in the city, including closing the doors of the Y.L. Peretz Jewish school.

"No one is under any illusion that the Polish Jewish community will ever return to its pre-war glory," says Shavei Israel's founder and chairman, Michael Freund. "Nonetheless, there are Jews living in Poland. They have Jewish children who need a Jewish education."

The new preschool opens at a time when Poland is experiencing a Jewish revival. Many Jews that remained in Poland hid their roots during the Communist era, but in recent years young people in the country have been discovering family history that has been concealed for decades and looking for ways to learn about Judaism and connect with other Jews in a now-democratic society.

"People are acting upon it because there is an incredibly open environment," where the population, especially in big cities, is "invested in idea of multicultural Poland," says Jonathan Ornstein, who has been executive director of the Jewish Community Center (JCC) in Krakow since it opened in 2008. Some Jews who grew up outside of Poland, like Ornstein, have decided to move and become part of the fledgling Jewish community that has begun flourishing there.

"A lot of the attention on revival in Poland is in cities like Warsaw and Krakow," says Ornstein. The opening of a Jewish school in a city other than these two urban centers "speaks of the depth of the Jewish revival in Poland," he adds, and says he believes it might help harness momentum—a functioning Jewish preschool could help grow the community in that city. "If we want to build a viable community here, we need certain fundamental things like education."

The preschool at the JCC in Krakow, for example, expands this year from two days a week to a full-time program. Ornstein hopes that when those children are ready for kindergarten, Krakow will open a Jewish one, and then follow that with a Jewish day school, to "keep them in the Jewish education system." These institutions take on a heightened importance in a place like Poland, he explains, since most young parents did not grow up knowing they were Jewish, let alone steeped in the Jewish religion, culture, history and values.

Originally from Krakow, Szychowska comes from a rare family whose Jewish roots were always acknowledged. Her grandmother from Warsaw survived the war with her own mother and grandmother, and began rebuilding a life in Krakow after the conflict finished. Szychowska—who was one of four women featured in the documentary The Return (her name then was Maria)—remembers going to the famous Jewish Culture Festival in Krakow with her mother and talking about being Jewish, but she was raised in a liberal rather than religious household.

When she got older, she became involved with Krakow's JCC, working with the student club and running the early childhood education program. She met her husband, a religious Jew studying in Krakow, at a Hanukkah party at the JCC, and has since become religious as well—praying, going to synagogue and covering her head, in keeping with the Orthodox beliefs. After spending a few years in Israel, she and her husband returned to Poland and settled in Lodz in August. It's important to her to raise their children in a religious household and for them to receive a Jewish education, she says.

Szychowska is "incredibly driven" and "a very strong person who takes a lot of initiative," says Ornstein, who's not surprised she decided to open a preschool from scratch upon arriving in Lodz. "Nothing in the world will stop her from realizing her idea."

Indeed, she's been preparing furiously for the school year, making all the necessary arrangements to make sure her students will be registered in the Polish education system and working with a public school nearby that will help supervise the new endeavor. Before leaving Israel, she consulted preschool and kindergarten teachers there at length and bought materials geared toward teaching children about Jewish prayers and holidays, as well as books, games, puzzles, videos and CDs in Hebrew. Her future students will get stickers that exclaim "Yafeh!" and "Kol hakavod!" (Hebrew for feedback like "Nice!" and "Great job!").

On Tuesday, in a small room provided by the Jewish Community of Lodz, she and a teacher she'd hired welcomed a small preschool class. Over the next few months, they'll play in the courtyard of the Jewish Community's building, go on outings to the museum, theater and zoo, and grow vegetables together in the garden, in addition to learning about Jewish holidays and religious traditions.

The group and classroom may be starting out small, but their presence is symbolic, says Shavei's Freund. In August 1944, the Nazis liquidated the Lodz ghetto and sent its surviving residents to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Now, just over 71 years later, "Jewish children will once again be singing Sabbath songs," Freund says. It's a "sign that the embers of Jewish life in Lodz have not gone out."

Correction: This article originally incorrectly stated that the room for the preschool was provided by the Jewish Community Center of Lodz. It was provided by the Jewish Community of Lodz, not JCC.

This piece has been updated to include the ages of the children who will be attending the school.