There is an old saying: If you're going to attack the king, make sure you kill him.

In the case of Chilean dictator General Augusto Pinochet, five U.S. presidents—from Jimmy Carter to George W. Bush—had a potentially lethal weapon to use against him but never unleashed it. That is, until the State Department released documents in October containing compelling evidence from as early as 1978 that Pinochet gave the order to murder Orlando Letelier in Washington, D.C. By then, however, the king was dead; Pinochet died in his bed in 2006. At the time, he was under judicial investigation for human rights crimes but was never convicted.

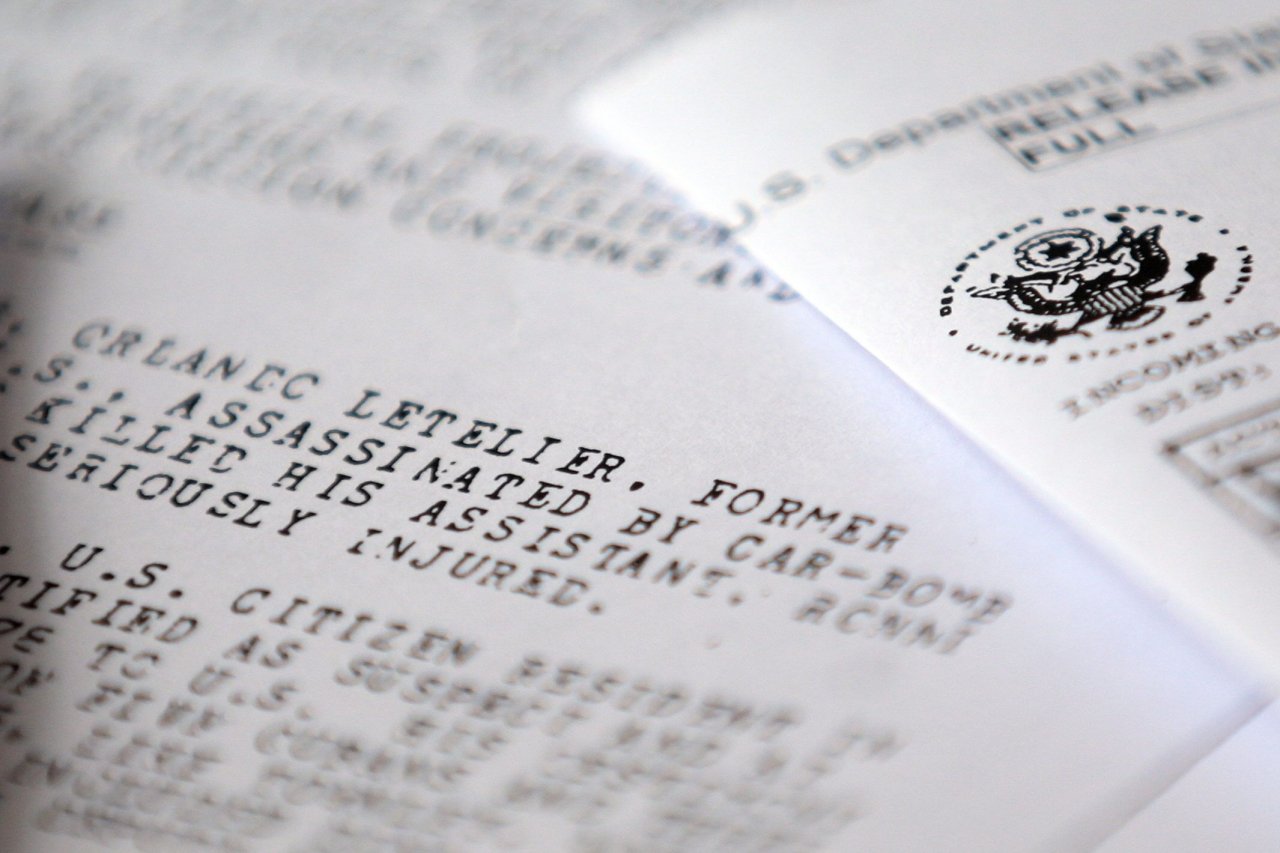

On September 21, 1976, a Chilean agent planted a car bomb that killed Letelier and Ronni Moffitt, an American woman who was with him, as they drove down Massachusetts Avenue. Moffitt's husband, Michael, who worked for Letelier, was also in the car and survived. Letelier, a former ambassador to the United States, had served as a high-ranking official in the leftist government of President Salvador Allende, who was overthrown in a Pinochet-led coup in 1973. Exiled to Washington after spending a year in a prison camp, Letelier had extraordinary access to D.C. power circles and was the most influential voice in the U.S. opposing Pinochet's dictatorship.

An FBI investigation led to the 1978 indictment of several Chilean officers, including the head of Chile's Directorate of National Intelligence, General Manuel Contreras, and a group of anti-Castro Cubans who carried out the bombing. But Pinochet emerged from the investigation unscathed, and he agreed to hand over the directorate agent who built and planted the bomb, an American named Michael Townley.

As the FBI arranged to take Townley back to the U.S. to face charges, the CIA was mining its abundant sources among the military and right-wing civilians in Chile about the bombing. The agency had close relations with them because during the Allende regime it had worked with Chile's most rabidly anti-Communist organizations to undermine the socialist government and encourage its overthrow.

A CIA report dated April 28, 1978, and sent to Washington showed that the agency already had proof of Pinochet's involvement in the killing. "Contreras told a confidant he authorized the assassination of Letelier on orders from Pinochet," the report said, according to a newly declassified document.

A State Department document refers to eight separate CIA reports from around the same date, each sourced to "extremely sensitive informants" who provided evidence of Pinochet's direct involvement in ordering the assassination and in directing the subsequent cover-up. Newsweek showed the reports to special agent Carter Cornick, who was working for the FBI in Santiago, Chile, in April 1978. "As you may suspect, none of this was new to us at the time," he says.

Cornick and his partner Robert Scherrer are credited with solving the Letelier murder. The former is now retired and lives in Virginia, just outside of Washington. He said the information against Pinochet was "hearsay"—gleaned from people who might talk to the CIA but would never appear in court. Formal charges against Pinochet were not possible, but there was another factor in the U.S. government's decision not to reveal what it knew. "The interests of the U.S., according to [the Department of] State," Cornick said, "were that Chile was a non-Communist country in Latin America and therefore no further punitive action against them was warranted."

In 1980, with the election of President Ronald Reagan, a Cold War conservative, there was a new ambassador to Chile, James Theberge, who thought along similar lines. According to a new document, Theberge criticized the damage caused by "punitive" measures against Chile during the previous administration of Jimmy Carter—a reference to the investigations, trials and pressure to obtain extradition of those indicted in the Letelier case. He instructed his staff to direct their efforts elsewhere, saying, "In my judgment and that of senior staff, the Letelier case offers no chance of success."

In the early 1980s, Chile was experiencing the first popular protest movement against Pinochet, and opposition groups on the left and center had united to push for a return to democracy. Public disclosure that the United States considered Pinochet guilty of a terrorist assassination would have had enormous impact in favor of the pro-democracy movement, according to Sergio Bitar, a former government minister and exile leader at the time.

Juan Gabriel Valdés, the Chilean ambassador to the United States, agrees. "It would have had a catastrophic impact on Pinochet," he says. "The United States could have changed history by simply accusing the man guilty of a crime committed in its capital, which it had the complete right to do and the power to do it."

The Republican-led State Department raised the issue again in the final years of the Reagan administration. The department was paying new attention to human rights, especially as a way to keep diplomatic pressure on the Soviet Union. Chile was still a dictatorship, but in 1987 Pinochet announced he would hold a plebiscite, with himself as the sole candidate, a move intended to prolong his rule for another decade.

The newly released documents show that Reagan's secretary of state, George Shultz, was trying to convince the president that it was time for the United States "to work toward complete democratization of Chile." Not surprisingly, Shultz's main argument to Reagan was that another decade of Pinochet dictatorship "would be highly dangerous for Chile and the region as a whole; inevitably it would lead to serious polarization of the Chilean population and a significant strengthening of the large (and growing, thanks to Pinochet) Moscow-dependent communist party."

The real surprise in Shultz's memo, dated October 6, 1987, is what it says about Pinochet's role in the Letelier-Moffitt killings. Shultz quotes from a report, which provides "what we [the CIA] regard as convincing evidence that President Pinochet personally ordered his intelligence chief to carry out the murders." Pinochet also led the cover-up to hide his involvement from the U.S. investigation, the report continues, adding a new and chilling detail: Pinochet was considering "even the elimination of his former intelligence chief [Contreras]."

The CIA information given to Shultz is similar in scope and content to the reports it generated in 1978. But Shultz said that the new report was stronger. "The CIA has never before drawn and presented its conclusion that such strong evidence exists of [Pinochet's] leadership role in this act of terrorism," he told Reagan.

Shultz raised the possibility of formally indicting Pinochet, assuming "more public sources of evidence" could be obtained. The hearsay nature of the information made legal action difficult, but the U.S. could have revealed the information as a political statement. "This," Shultz continued, "is a blatant example of a chief of state's direct involvement in an act of state terrorism, one that is particularly disturbing both because it occurred in our capital and since his government is generally considered to be friendly." However, for whatever reason, the White House demurred.

The opposition ultimately prevailed in the plebiscite with a "no" campaign against Pinochet. Chile held elections in 1990, and a new president, backed by the center-left Concertación alliance of political parties, restored limited democracy. But the generalissimo remained influential as head of the armed forces until 1998.

In October that year, there was another historic opportunity for the U.S. to announce what it knew about the Chilean general. Pinochet was detained in London on human rights charges associated with the Operation Condor assassinations, including that of Letelier. President Bill Clinton ordered the declassification of 23,000 documents on Chile and human rights, but kept the Shultz memo and the CIA reports on Pinochet hidden.

While lamenting the long secrecy, Valdés, the Chilean ambassador, said he is deeply grateful to the Obama administration for quickly releasing the documents after he made a formal request on behalf of his government.

Reading them today, you can still see the markings on the documents from the 1998 review: "SECRET" and "DENY." Now the markings are crossed out. Decades after the CIA discovered the evidence of Pinochet's guilt, they finally bear a simple unambiguous stamp: "RELEASE IN FULL."

John Dinges is the author of two books on the Letelier assassination and other human rights crimes in the Southern Cone: Assassination on Embassy Row (Open Road, updated in 2013) and The Condor Years: How Pinochet and His Allies Brought Terrorism to Three Continents (The New Press, 2003 and 2013).