"Assad is a heartless killer!" rages Ruslan, a middle-aged worshipper at Moscow's biggest mosque, just days after Russia's dramatic entry into Syria's civil war in support of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. "It's a disgrace that the Kremlin is supporting his bloody regime," he adds, as an unseasonal snowstorm obscures the mosque's golden domes. Another man arriving for evening prayers, a bearded 20-something named Arslan, thinks the opposite. "Russia is doing the right thing in backing the Syrian authorities against ISIS and other terrorists," he says, adding that he has heard "nothing at all" about human rights abuses committed by Syrian government forces.

It's hard to say what most of Russia's estimated 20 million Muslims—around 14 percent of the country's population—think about President Vladimir Putin's decision to take military action against Islamic State militants (ISIS) and other opposition groups in Syria, but the move is fraught with dangers. The history of Islam in Russia is one of frequent confrontation, from the 19th-century uprising by Muslim rebels in the country's North Caucasus region to the separatist and then Islamist wars that devastated Chechnya in the mid-1990s and early 2000s.

Related: With Stepped-Up Syrian Intervention, Putin is Playing a Greater Game

Unlike Assad, who hails from the minority Alawite sect, Russia's Muslims overwhelmingly belong to Islam's dominant Sunni branch. This is something they have in common with the myriad opposition forces battling for control of Syria's war-torn cities. Putin may have been applauded by some for seizing the initiative in Syria, but by backing Assad's mainly Alawite army, as well as its Shiite allies, who include Hezbollah and elite Iranian troops, he risks inflaming Sunni passions at home.

The Kremlin is deeply suspicious of independent Muslim organizations, and security services carried out a sweeping crackdown ahead of last year's Winter Olympics in southern Russia. "They consider everything and everyone that they do not control to be an extremist," says Harun Sidorov, head of the National Organization of Russian Muslims, an independent Islamic movement whose members have faced police pressure, including raids and arrests.

As many as 500,000 Muslims in Russia may indeed sympathize with ISIS, according to a cautious estimate by Alexei Malashenko, an expert on Islam at the Carnegie Moscow Center think tank. "These are people who want to build a state founded on the principles of Islam," he says. "Many of them say ISIS is fighting for social justice and for fair government. Others like the fact that it is fighting against the West."

ISIS has mounted a slick Russian-language recruitment campaign that includes a magazine, Istok, and a dedicated propaganda channel, Furat Media. According to Putin, 5,000 to 7,000 people from Russia and other former Soviet states, many of the Chechens, are fighting for ISIS in Syria. Earlier this year, Islamist militants in the mainly Muslim North Caucasus pledged their allegiance to ISIS's leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. In response, Chechnya's pro-Kremlin leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, appealed to Putin to send Chechen fighters to Syria to "destroy" what he called ISIS "devils."

Muslim criticism in Russia of Putin's Syria adventure has been largely restricted to furious social media posts and online articles. So far, there has been little sign that Russia's Muslims are about to take to the streets against the military campaign. Both experts and government critics say this reluctance to speak out is partly due to a fear of the possible consequences of dissent, rather than an indication of tacit approval. "Muslims in Russia have been frightened into silence by the repressive policies that have been methodically carried out throughout Putin's rule," says Airat Vakhitov, a former imam from Russia's Tatarstan region, who was arrested in 2005 on what he says were trumped-up terrorism charges in Russia. He was later released for lack of evidence and now lives abroad.

Kremlin-loyal Muslim leaders have offered their unwavering support for Russia's airstrikes in Syria. On October 2, the long-serving head of Russia's Council of Muftis, Ravil Gainutdin, issued an urgent appeal for calm, calling on his fellow Muslims to not "politicize" the Kremlin's involvement in the conflict. Sprinkling his statement with verses from the Islamic holy book, the Koran, Gainutdin also expressed the hope that Russia's military action would not lead to interfaith strife among the global Islamic community, or ummah . Gainutdin's comments were echoed by subordinate muftis across Russia.

The sole dissenting voice was that of Nafigulla Ashirov, a co-chairman of the Council of Muftis, who in early October told the BBC's Russian-language service that there should be no foreign "interference" in Syria's civil war. But Ashirov, a radical figure who in 2001 expressed his enthusiastic support for the Taliban, quickly backed down. In subsequent interviews, he refused to comment on Russia's airstrikes, and he tells Newsweek he has "no opinion whatsoever" on the subject.

Related: How Putin Wins in Syria

While the United States says the vast majority of Russia's airstrikes in Syria have mainly targeted the "moderate" opposition to Assad, on October 6 the independent Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said Russian jets hit ISIS fighters near the ancient city of Palmyra, where the jihadi movement destroyed a 2,000-year-old Roman arch of triumph earlier this month. Both ISIS and the Nusra Front, an Al-Qaeda offshoot in Syria that has also been targeted by Russian missiles, have since urged Muslims to wage jihad against Russia.

"It is likely there will be a response from North Caucasus–based militants with links to ISIS," says Gregory Shvedov, editor of Caucasian Knot, an independent online news service. "They certainly have the capacity to set up attacks in Moscow and other big cities."

On October 11, shortly after Newsweek spoke with Shvedov, counterterrorism agents in Moscow detained 12 people they said were planning a bomb attack on the city's public transport system. Security officials said at least one of the suspects, a Chechen, had received training at an ISIS camp in Syria. But the details of the alleged bomb plot were hazy and often contradictory. The timing of the arrests—they came shortly after Putin had spoken on national TV about the need to eliminate Russian ISIS fighters in Syria before they returned home—also sparked speculation that they may have been part of a propaganda operation to bolster public support for the Kremlin's military campaign.

Whatever the truth, news of the arrests frayed nerves. Although Moscow has not had an attack since 2011, when over 30 people were killed in an Islamist suicide bombing, more than 3,000 Russians have lost their lives in attacks Russia considers terrorism since Putin came to power in 2000. But if a new wave of violence is coming to Russia, there is little that counterterrorism officials can do to prevent it, says Andrei Soldatov, a journalist and author who is an expert on the Russian security services. "Russia's counterterrorism system was designed in the mid-2000s, and its main goal is to prevent groups of militants from getting control over regions or important facilities, not to prevent terrorist attacks," he tells Newsweek. He also described security measures in place in Moscow and other Russian cities as "largely dysfunctional."

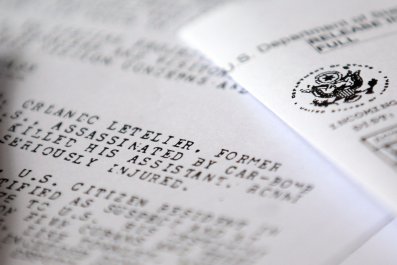

Related: Did American Spy Agencies Miss Early Signs of Putin's War in Syria?

Back at the mosque in Moscow, a middle-aged woman in a headscarf frowns when I ask her opinion of the Russian missiles raining down destruction on Assad's Sunni opponents. "I have very strong views on that," she says, "but I wouldn't like to state them out loud." Then she pauses. "But this is very dangerous," she whispers. "Very dangerous, indeed."