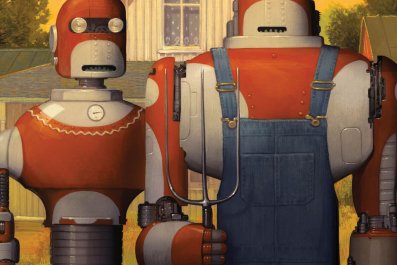

Sitting across from me for our interview, Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky demonstrated why artificial intelligence robots won't take over the job of entrepreneur anytime soon.

No robot would ever be as crack-brained and heedless as Chesky was at his company's beginning—actually, as any entrepreneur must be today. In this warped era of company creation, the only good business ideas are really bad ideas. Code that into an IBM Watson and watch its circuits melt.

The interview with Chesky took place at New York University, in front of an audience of mostly students who someday want to start companies. Chesky retold Airbnb's creation story. He and Joe Gebbia, recent graduates of the Rhode Island School of Design turned jobless roommates in San Francisco, couldn't afford their rent. A major design conference was coming to town, and hotels were sold out. The roommates blew up three airbeds and put up a website offering to rent them out and serve cereal in the morning. Hence AirbedAndBreakfast.com. They got three paying customers.

"Does that sound like a big idea?" Chesky quipped. "I remember someone saying to me, 'Don't worry about your idea. If it's any good, everyone will dismiss it.'"

I've been hearing a lot of that lately. Bryan Roberts, a venture capitalist at Venrock, told me he has to look for what he calls non-consensus ideas. These companies have to have "something most people think you can't surmount, or that if you do surmount, no one will care." Snapchat, for instance, falls into that latter category. Early on, a lot of people wondered why anyone except sexting teenagers would care about a service that disappears their naked selfies. Today, the company is valued at $16 billion. Go figure.

Why search for non-consensus? In this era of constant connectivity and social media, everyone knows what everyone else is doing instantly. Cloud services and open-source software allow anybody with an idea to get it up and running quickly for very little money. Add all that together and the second an idea seems sane, 30 companies are already doing it and fighting for attention, investment and customers. That's not the kind of business that's going to blow up into a multibillion-dollar, world-changing enterprise.

A non-consensus company like Airbnb or Snapchat buys time in the shadows to build a business that hardly anyone thinks is worth building. Then another phenomenon of our ultra-connected age kicks in. As Roberts says, "Things go from non-consensus to consensus very quickly, but by then you [the company] have some competitive advantage that's hard to surmount." Nobody sees it, and then—boom!—it's everywhere, constantly tweeted, liked, pinned and shared. Slack, Dropbox, YouTube—you've watched it happen a hundred times. For Airbnb, that takeoff moment came in 2011. Today, Airbnb offers more rooms than Hilton, Marriott and Hyatt combined. It's been valued at $25.5 billion.

The speed is what's new. Non-consensus ideas have always driven the greatest innovations. (When King Gillette started selling disposable safety razors in 1904, most men wondered why they'd give up their straight razors.) But in the past, starting a business often involved manufacturing, and word spread by advertising. The conversion to consensus was more like a journey than a light switch. New gadgets could be protected by patents for decades. Today, a fraction of startups even file for a patent. There's no time. The better protection is having potential competitors think you're nuts for just long enough that they can't catch up once you prove you're not.

The challenge of searching for non-consensus ideas, then, is separating good non-consensus ideas from ideas that just plain suck. In the earliest stages, as when Chesky was renting blow-up beds, the two look the same. In honest moments, every investor or entrepreneur will tell you they can't tell the difference. Chesky's advice: "You just have to build a solution for a problem in your own life." Solve your own small problem, and it might later scale to solve a lot of people's bigger problems.

In fact, when you think about it, the legendary entrepreneurs have understood that their jobs weren't just to invent something. That may be the easy part, the part someone like Chesky can stumble into. The real job is changing people's minds. A non-consensus idea by definition has no demand. No one thinks he wants or needs it. Inventing Airbnb was one thing. Convincing a mass market that it's wonderful to stay in other people's homes while traveling has been the company's real victory.

This circles back to worries that AI will get so smart it will take over all our jobs. Days before talking with Chesky, I met with Joseph Sirosh, who's developing machine learning at Microsoft. He discussed how machines are getting amazingly good at predicting what to do next based on past data. They can suck up all the medical research and patient data ever created and diagnose a rare disease most doctors wouldn't even know about.

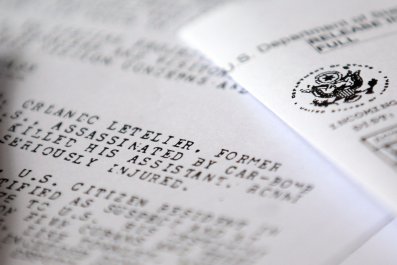

But great non-consensus ideas come from the opposite direction. As Sirosh said, past data will always show that a non-consensus idea will fail. Use AI to analyze Airbnb in 2008 and it would've suggested Chesky stick to his other idea, making politically themed breakfast cereal. Chesky and Gebbia actually funded Airbnb by selling boxes of Obama O's and Cap'n McCain's.

In this modern age, the great value of humans—our ultimate triumph—seems to be our willingness to do things that make absolutely no sense.