There is the little girl who had a tumor on her kidney and the boy who had cancer of the brain. People get cancer everywhere, but in southeast Los Angeles County, the latest battleground over lead contamination in the United States, people talk about cancer as if it were a tornado: this house, two houses after that, my mother, my husband, my cousin. Sometimes, all of the above.

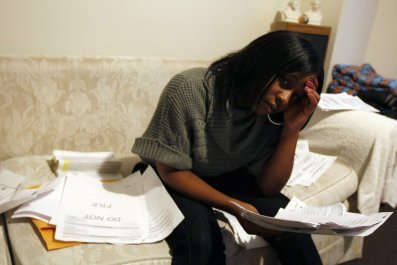

Children here are born early, already ailing. Amelia Vallejo has six, all born premature. All six have breathing troubles, as do many children in her neighborhood, most of them from working-class Latino families. Vallejo's first five babies got off relatively easy. Her youngest, Michael, was born with severe developmental delays. He has difficulty hearing and seeing. "My son's in diapers. He is 5," Vallejo says with tragic matter-of-factness. We are sitting in her neat living room on South Herbert Avenue. Bright plastic toys stand stacked against the walls. Some of these should be outside in the yard, Vallejo explains apologetically, but her kids don't play there anymore, not with lead soil readings of more than 1,400 parts per million.

"They didn't care," Vallejo says. "They were making money." They are Exide Technologies, one of the world's largest producers and recyclers of lead-acid car batteries. Until last year, it operated a recycling plant in nearby Vernon, the famously corrupt and polluted municipality that was the setting for the second season of HBO's True Detective. Though state regulators repeatedly warned Exide that it was releasing dangerous chemicals into the atmosphere—not only lead but also arsenic, benzene and 1,3-butadiene—the warnings were never especially stern, and so Exide never heeded them until, finally, the Department of Justice shut down the plant last spring. (Exide did not respond to requests for comment for this article.)

For many here, that was far too late. Cynthia Harding, the interim director of public health for Los Angeles County, recently wrote that within a 1.75-mile radius of the Exide plant, the "contamination potentially affects 5,000 to 10,000 homes, and represents a continuing risk to tens of thousands who reside or work in the area." Some soil lead readings suggest that children who play in a front yard here frolic on top of what is essentially a hazardous waste site. Arsenic, benzene and 1,3-butadiene are all known carcinogens; the residents of East Los Angeles and surrounding communities have been ingesting them for decades.

The closing of the Exide plant in March 2015 has not brought closure to what longtime Los Angeles radio journalist Warren Olney calls "one of America's worst cases of environmental pollution." The similarities to the situation in Flint, Michigan, are both eerie and depressing: poor people of color poisoned by lead as most public officials look on with a dismaying lack of concern. "We are not cute little penguins," one local activist says in a Los Angeles Times documentary about Exide. "No one's coming to save us. We need to fight for ourselves."

But there is work here that is beyond the scope of activists. Recently, California Governor Jerry Brown allocated $176 million for the cleanup effort, but that is only about a third of what some think it will take to make sure these communities are clean, or at least cleaner. As for the human costs, they are impossible to quantify.

Lately, the fight has been joined by Hilda Solis, a former U.S. secretary of labor who became a Los Angeles County supervisor in 2014, representing a district that is 72 percent Hispanic and where the per capita income is $18,000. Solis has allocated $2 million in county funds to create three-person teams that can quickly test properties for lead; she was also responsible, in part, for making sure that the plaints of her constituents were heard in Sacramento.

I toured the district with Solis on an achingly perfect Southern California afternoon that renders all thought of toxins obscene. We visited Nicolasa Ramirez, who lives in a squat blue house in Commerce, with a front yard that functions as an herb garden. There are plantings in her backyard too, as is common in the neighborhood. Ramirez knows, though, that she cannot eat the produce from her garden: The soil has been tested at more than 1,000 parts per million for lead. The safe limit in California is 80 parts per million. Her granddaughter, Lali, had the tumor on her kidney: A picture she drew hangs in the house's front window, while a Jesus statue looks over the tainted garden. Lali recovered, but many children have not.

The comparison to Flint is irresistible, but Solis thinks her district differs in a critical respect. "It's worse," she says.

The Armpit of Los Angeles

If you visit the website of the Association of Battery Recyclers, you might think you've stumbled upon the gentlest industry since kitten husbandry. Above the image of a road winding through a forested mountain landscape, the industry group touts its 99 percent recycle rate in North America, which leads to the reclamation of 150 million batteries annually, thus helping "make America cleaner and stronger."

Battery recycling is a messy enterprise whose main purpose is not altruism but the recovery of the valuable lead inside. Because of U.S. regulations, many recyclers have moved their operations to Mexico, sometimes shipping batteries there illegally. A McClatchy Newspapers investigation in 2013 found that whereas the United States had 154 battery smelters four decades ago, the number had fallen to 14.

Exide makes and recycles batteries in the United States, though many communities have come to resist its presence. In addition to the DOJ-forced closure in Vernon, it also recently shuttered a plant in Frisco, Texas. An investigation of Exide's plants across the nation by the Los Angeles Times found that the company "has left a trail of pollution and health worries across the country" and that, between 2010 and 2013, "seven Exide operations have been linked to ambient airborne lead levels that posed a health risk."

Exide came to Los Angeles in 2000, inheriting the Vernon plant through its acquisition of GNB Technologies. Lead smelting had started at the site in 1922; in 1949, filters there captured 128 tons of lead emissions. It 1981, the California Department of Toxic Substances Control granted the plant a temporary permit under which it continued to operate. In 1999, the DTSC "found lead at levels of 40 percent in the sediment at the bottom of the storm water retention pond and required the Vernon plant's operators to clean it up," according to public radio station KPCC. The agency "'was clearly aware' that the storm water drain lines were bringing lead particulates to the pond and that the lines were reportedly 'perforated' so that they could leak into the soil on purpose." Over the next decade, the plant continued to operate with the same disregard for public safety, although local activists were making it ever harder to do so with impunity. So were regulators, finally. A 2013 analysis of air quality found that Exide was potentially elevating the cancer risk for 110,000 Angelenos; later that same year, 252,000 people were estimated to be facing "chronic hazards" from the plant. There was a temporary closure of the plant in 2013, then the permanent one, ordered by the DOJ, last year.

"After more than nine decades of ongoing lead contamination in the City of Vernon, neighborhoods can now start to breathe easier," said acting U.S. Attorney for the Central District of California Stephanie Yonekura in a statement. Exide was ordered to pay $50 million in cleanup costs.

"They pollute and leave," says Monsignor John Moretta, of Resurrection Church in Boyle Heights who has been one of the central organizers in the fight against Exide. Moretta has few illusions about his neighborhood, whose residential streets taper off into tracts of warehouses and factories: "the armpit of L.A.," he lovingly calls it. A large man with a wry sense of humor, he has spent years trying to hold Exide accountable. This has tested his faith, this wanton disregard of public health. "There's nothing like it," he says, "in the history of California."

Cancer-Causing Books

In late October, an old oil well being used for gas storage in the upper-class San Fernando Valley community of Porter Ranch, on the hilly northern edge of Los Angeles County, ruptured. The ensuing leak of methane became the worst in American history and, according to some, the worst environmental disaster in the United States since the Deepwater Horizon blowout in the Gulf of Mexico. The blown well, which was capped in late February, caused immense damage to the environment, but methane is not, as far as anybody knows, a toxic gas. Nobody got cancer. Nobody died.

On January 31, a Los Angeles Times editorial headlined "Two Disasters, Two Responses" lambasted Governor Brown for his neglect of the Exide disaster, which it contrasted to his handling of the methane leak in the Valley. "It's time to treat East L.A.," the editorial board told the governor, "with the same urgency he has shown at Porter Ranch."

People here make no attempts to disguise their bitterness on this discrepancy. Moretta jokes to me that he is going to rebrand his neighborhood "Boyle Heights Ranch" in hopes of attracting more media interest. The imbalance is indeed striking: While The New York Times has published nearly a dozen articles about Porter Ranch in the last several months, it has never covered what Exide has done in Vernon. "We're too dark to get the attention Porter Ranch is getting but not dark enough to get the attention Flint, Michigan, is getting," one local activist complained at a public hearing.

Similarly, the agency that could have halted Exide's dumping, the DTSC, seemed to have little interest in taking punitive action. A Los Angeles Times investigation conducted by reporter Tony Barboza found that "over more than 15 years, Exide paid $869,000 in penalties. Most were assessed in the last two years," as health studies began to make the hazards of lead smelting ever more clear.

A spokesman for the DTSC described the state's response in Vernon as "aggressive."

Industry's Noxious Wake

I drove with Solis and her staff from Boyle Heights to the Exide plant in Vernon. The ride from rows of small, neat suburban homes to vast industrial tracts is distressingly short. Here is the converse of the Los Angeles that everyone knows: the beaches of Malibu, the gated villas of the Hollywood Hills. Here are the infernal furnaces of the city. Close by are several elementary schools. People here simply accept that they must live in industry's noxious wake; it's the price they pay for being poor.

We walked the perimeter of the plant, trying to peer through an opening in the fencing. On the other side was a lagoon of what appeared to be wastewater. At the entrance to the facility, I took some pictures while an unhappy guard looked on. Really, though, there was nothing to see: The best poisons work under the cloak of invisibility.

The site is contaminated from years of unsafe operation; Exide wants to restart its kettles to reclaim some of the lead from the waste that remains, but locals find the notion of letting the plant run again preposterous.

There are probably not many practicing epidemiologists among the residents of East Los Angeles, Boyle Heights and other nearby communities, but plenty of amateur ones who have learned about cancer clusters, bioaccumulation and case-controlled studies.

I asked Moretta when he will know that the Exide crisis is over. "When you walk down the street," he says, "you see kids playing in the yard, and you don't worry about it."