The three gunmen pulled up around 4 a.m. on May 24, 2013. They jumped the fence for a generic South Florida gated neighborhood and then used a brick to break a rear window of the house they hoped to rob. Frances Jeudy and his roommate Frantz Decoste were asleep in an upstairs bedroom when the three gunmen yelled "FBI!" and kicked in their door. Instead of panicking, the two men grabbed their own guns and opened fire. The gunmen fled, two back into the night and the third into an upstairs bathroom, where he traded shots with Jeudy and Decoste before dropping his 9-millimeter handgun and surrendering. "It was supposed to be a robbery," he whimpered. "I'm trying to feed my family."

Jeudy called 911, and as the police pulled up, he walked out of the house with a gun at his side and announced, "I got him!" The Miramar Police Department officers went inside and handcuffed the bloodied robber. The cops noticed immediately that the house reeked of marijuana; they obtained a search warrant and tossed the house that same day. Inside, they found a dozen gold and diamond necklaces, seven MacBooks and $174,000 in cash. More important, the police found 500 debit cards issued by H&R Block and Bancorp, plus five U.S. income tax refund checks in other people's names.

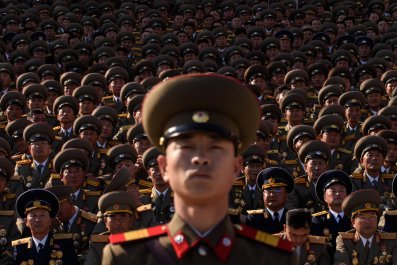

That botched home invasion led to a federal indictment, but it wasn't for the hapless robbers. The feds went after the guys inside the house and their crew—Jeudy, Decoste and four others—who were part of a more profitable and less risky newer crime that loots an estimated $6 billion a year from the IRS: stolen identity refund fraud, which federal agents call SIRF. Criminals have used stolen personal information such as social security numbers and dates of birth to file fraudulent tax returns and steal refunds for decades. But electronic filings and sites like TurboTax.com have sped up the process, making it easy for criminals to quickly file large numbers of returns, and there has been a massive increase in the number of SIRF cases in the past five years. "Drug dealers and other violent criminals have found it a lot easier and safer and more lucrative to steal people's identity and file false income tax returns than it is to sell drugs on the corner or hold up a liquor store," South Florida U.S. Attorney Wifredo Ferrer tells Newsweek. "Personal identity information is the new crack cocaine for criminals because it's very valuable. Those numbers are information that can be used to steal thousands or millions of dollars."

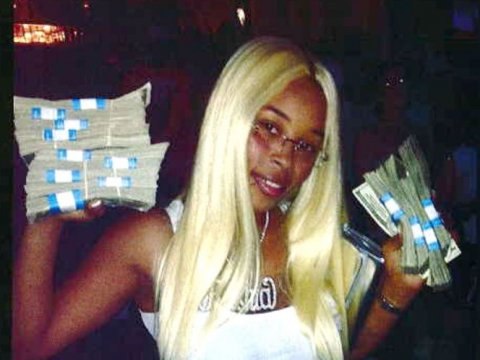

When IRS investigators searched the laptops found at that house in Miramar, about 20 miles north of Miami, they found cellphone photos of computer screens at a medical center—each photo showing about 12 names, social security numbers and dates of birth. Investigators dug deeper into those hard drives and uncovered 29,000 social security numbers and a history of visits to TurboTax.com and TaxHawk.com, as well as software that masked the identifying IP address of the computers. When investigators matched up the personal information found at the Miramar house with returns filed with the IRS, they found thousands of bogus returns claiming tens of millions of dollars going back to 2011. The six men—who filmed music videos together and go by nicknames such as "Money King" and "Chadillac"—were indicted on SIRF charges, pleaded guilty and could face decades in federal prison when they are sentenced this month.

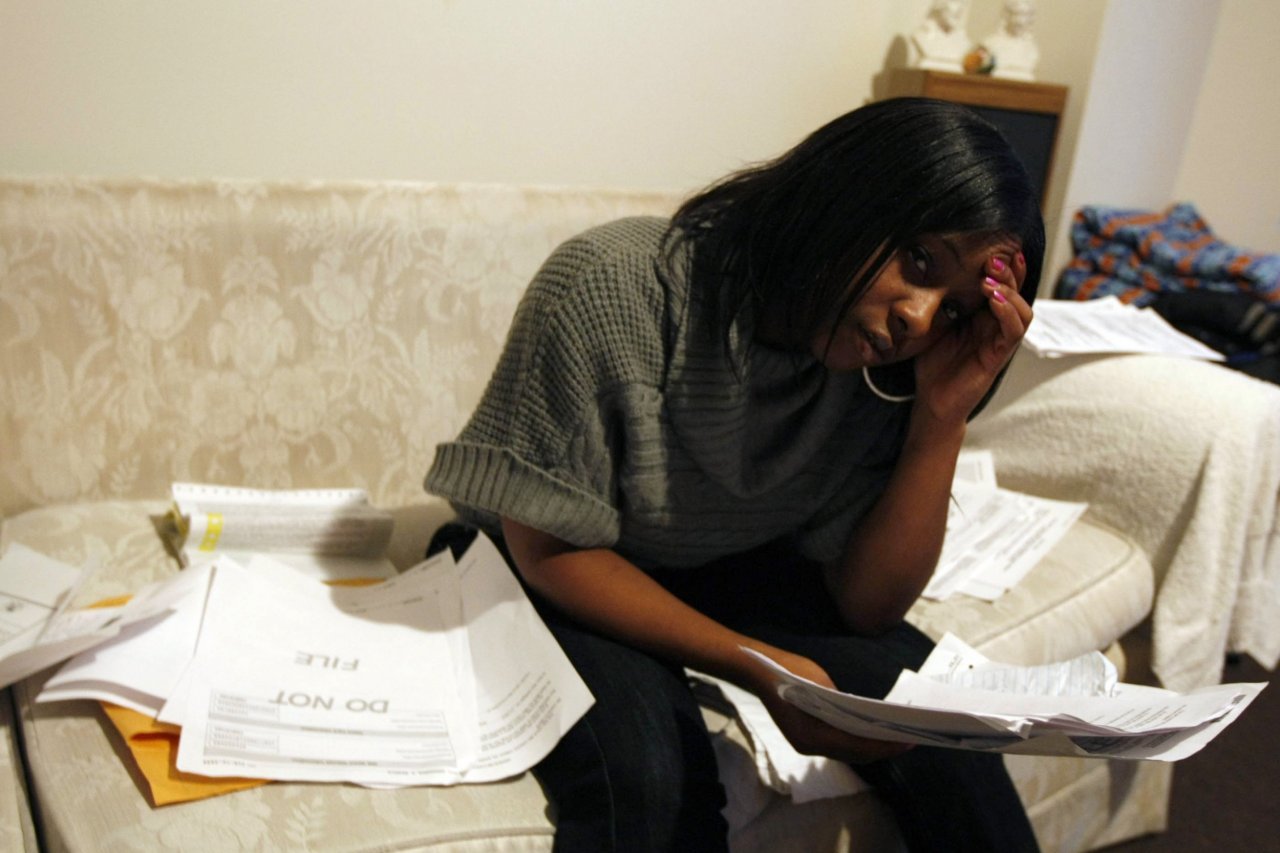

The scheme uncovered in Miramar is similar to crimes perpetrated across the country, from Miami to Anchorage. Scammers steal personal information from hospitals, nursing homes or banks, then use it to file bogus tax returns, with the refunds sent to mailboxes or debit cards they control. The phony returns usually have a mix of genuine information—like someone's real name and social security number—combined with made-up addresses and incomes. The crooks submit the returns early in the tax season because if they file after the real taxpayer, the fake return will get bumped, and the crook won't make any money. SIRF operations can range from simple outfits run by a single person filing returns from their basement in their underwear to complex crews. Last year, eight people in Alabama and Georgia were sentenced for their roles in one SIRF ring that stole millions. In that operation, one woman who worked at Fort Benning stole personal information from soldiers deployed to Afghanistan, another woman swiped information from the Alabama Department of Corrections, other people used those stolen names and numbers to file the returns, and a woman who worked at a Wal-Mart money center cashed the refund checks.

The IRS criminal investigation division launches an investigation when local cops stumble onto fraud crews like the one in Miramar, when they get referrals from state and federal law enforcement agencies and when large amounts of personal information are stolen in data breaches. Five years ago, IRS special agents spent about 3 percent of their time investigating identity theft, but today agents devote 20 percent of their time to the increasingly popular crime. And in SIRF hotbeds such as Miami and Tampa in Florida, Alabama and Georgia, agents can spend 50 percent of their time chasing identity thieves. "It may be due to the humidity," says a law enforcement official, joking about why certain Southern jurisdictions see more than their SIRF share.

But crooks can also steal tax refunds on computers thousands of miles from the football powerhouse states of the Southeastern Conference. A Bulgarian man was extradited to the U.S. and pleaded guilty last year to hacking into the networks of four U.S. accounting firms, stealing their clients' tax filings and using the information to claim $6 million in refunds. "SIRF crimes have evolved over time, and now we're seeing a more sophisticated class of criminals who are mining the Internet for information," says Caroline Ciraolo, acting assistant attorney general of the Department of Justice's Tax Division.

Criminals are now buying and selling the personal information necessary for tax fraud on the darknet. Richard Weber, chief of the IRS criminal investigation division, says his investigators have seen specific chatter from criminals preparing for the next filing season and that information on the darknet is sold in bulk, to multiple buyers. "It's very organized, it's significant, and it's scary." The IRS criminal investigation division also created two new cybercrime offices in the past year, one on the East Coast and one on the West Coast.

Even facing off against new filters, increased enforcement and a brigade of IRS special agents, street-level hustlers still see SIRF as easy money. "South Florida is like the cesspool of fraud," says Miramar Police Department Detective Jay Fox, who works on tax fraud task forces with the IRS and Secret Service. "The chance of getting caught is slim." SIRF crews often get the personal information they need by using what they call a "plug"—someone on the inside—usually a woman who works in a nursing home or school or hospital and can steal names and social security numbers. The SIRF crews, made up of mostly men in their late teens or early 20s, still jack cars and sell drugs, but they keep the calendar of a certified public accountant. "During tax season, they try to get away from the drug activity so it doesn't draw too much attention to their house, and that's when they're doing the tax fraud," Fox says. And the hustlers have fun spending their loot, renting houses for $4,000 per month and buying lots and lots of sneakers. "They have so many Jordans," Fox says. "My partner just went on a case—they had a two-car garage, and I swear it looked like a Foot Locker."