It was only a matter of time. Given the trade surpluses China has built up year after year, its strengthening currency and its lengthening roster of globally ambitious companies, it's no surprise that the wave of Chinese foreign direct investment in major Western economies has arrived.

In the first quarter of 2016, Chinese companies have executed or proposed deals worth $100 billion for foreign assets across a range of industries (twice the amount U.S. companies have paid for foreign assets abroad over the same period). Among the highest-profile deals: Chinachem offered $43 billion for Swiss agrochemicals giant Syngenta, Haier paid $5.4 billion for General Electric's appliance business and conglomerate HNA group bought electronics distribution giant Ingram Micro. Others are almost surely coming. E-commerce giant Alibaba, to take one example, is said to be sniffing around in the entertainment and technology space.

The surge of Chinese companies buying high-profile Western assets was inevitable for two reasons. The first is that one of the principal ways all the foreign exchange the country has built up over the years (more than $3 trillion worth) can be recycled is through foreign direct investment; the second is that Chinese companies, both state-owned and privately held, are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Over a decade ago, state-owned oil giant CNOOC made a ham-handed attempt to buy California oil giant Unocal; when that bid collapsed—among other reasons, it generated political controversy in Washington—China Inc. concentrated its foreign investments in the developing world, focusing mainly on acquiring commodities it needed to fuel the past decade of China's rapid growth.

As the pace of higher-profile deals in the West accelerates, it will bring a predictable backlash—one that the CNOOC-Unocal imbroglio in 2005 foreshadowed. When a similar wave of Japanese direct investment hit in the 1980s and '90s, it poked a national nerve of economic insecurity. Politicians and the press worried that Japanese corporations were taking over the world, and the binge of foreign direct investment was often cast in military terms—including, alas, by this magazine and this correspondent (when Sony bought Columbia Pictures, a cover story I wrote was headlined "Japan Invades Hollywood" and featured the Statue of Liberty cloaked in a kimono, a memory too painful to repress).

You got a whiff that the backlash is coming in a CNBC interview on March 30 with a hotel industry analyst about the latest big-time offer from China for a high-profile U.S. company: Anbang Insurance Group's $14 billion bid for Starwood Hotels and Resorts, in which the little-known Beijing-based company squared off against Marriott International in a bidding war. With a straight face, the analyst said one of the hurdles confronting the Anbang bid for Starwood was that it would face a CFIUS review.

CFIUS—the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S.—is a government group that reviews foreign investment for national security concerns. Starwood owns a bunch of hotel chains—from the posh St. Regis brand to trendy W's. CFIUS is not required to review every foreign investment, just those the committee judges might have national security implications. The notion that Starwood fits into that category is, to say the least, far-fetched. When pressed on CNBC, the analyst said it might be possible that there are hotels near military bases. Why, exactly, that matters was never stipulated.

On March 31, Anbang—citing "various market conditions"—abruptly walked away from the Starwood deal. But make no mistake, there are more deals from China coming, and at least some of the unease they will undoubtedly generate will be justifiable. On e reason the hysterical reaction to Japan was, in hindsight, so unwarranted is that Tokyo was (and remains) one of America's closest allies. And while Japan's general technological superiority at the time did raise some legitimate concerns—in the realm of both national security and the health of the overall U.S. economy—those faded quickly when it became apparent that Tokyo was anything but an economic juggernaut.

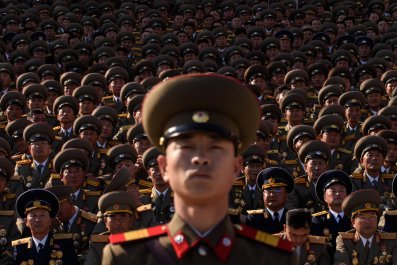

China is different. It is obviously not an ally and, as the last decade has shown, is arguably becoming Washington's chief geopolitical rival (though not an outright adversary like the former Soviet Union). And though not as technologically advanced as Japanese companies, Chinese ones are rapidly climbing up the ladder, and one of the ways they try to do so is by acquiring Western technologies and businesses. That, for example, is part of the thinking behind Chinachem's offer for Swiss-based Syngenta.

Chinese companies with the wherewithal to make big foreign transactions, moreover, are often not privately owned. When Japan was in its heyday, we used to throw around the term "Japan Inc." to describe the clubby, insular style of Japanese capitalism. Many of the Chinese corporations going abroad actually are "China Inc."—they are owned or controlled by the government. Thus, it is very often the case that strategic moves they make are not solely to increase market share here, or acquire a technology there, all in the name of eventually driving up the acquiring company's stock price. There can be other reasons—national security interests defined by Beijing—and it is perfectly reasonable for foreign governments to try to figure those out, when warranted.

Take CNOOC's bid for Unoc al in 2005. C NOOC is China's primary developer of offshore oil and gas, and it is state-owned. It was reasonable for CFIUS to review the security implications of that bid. But if, say, Mitsui Oil of Japan had made the bid, a CFIUS review would have been a waste of everyone's time.

Another reason foreign governments might cast a wary eye on some Chinese acquisitions is that such cross-border investment works only one way. That is, it's fine for a state-owned Chinese company to try to buy a European agro-business, but good luck with the reverse: Foreign companies simply cannot buy state-owned companies in China. They are not for sale. (In this, there are some similarities to the Japan experience, because major Japanese companies often have interlocking corporate ownership structures that make them invulnerable to a hostile takeover, foreign or domestic. See, for example, the Mitsubishi group companies.) Economists argue over whether so-called reciprocity should matter when it comes to considering foreign mergers and acquisitions, but it is something governme nts can legitimately consider.

Since the CNOOC debacle, Chinese companies—at the government's urging—have been far more circumspect with their Western acquisition targets. There is little controversial about the targets of the deals announced since the beginning of this year, unless you think the bars at W Hotels are a national treasure to be protected at all costs from the predacious Chinese commies. That might serve to mitigate any hysteria about the world being "taken over'' by China Inc. On the other ha nd, as this year's political campaign illustrates, the United States seems to be having a national nervous breakdown, and one of the causes is economic insecurity. As a result, whoever is elected—Hillary Clinton included—is no doubt going to be looking at Chinese acquisitiveness carefully.

But as the boom of mergers and acquisitions unfolds, keep this in mind: It is not necessarily China's economic brawn (or the West's shortcoming) that is driving it. It is, arguably, China's increasingly evident economic weakness that is helping propel the increasing amount of outbound foreign direct investment. As its economy loses strength and a continuing anti-corruption crackdown makes CEOs of both state-owned and private companies nervous, capital flight ensues. Acquiring Western assets—wh ether it's wealthy indivi duals buying high-end Manhattan apartments or Anbang purchasing the Waldorf Astoria Hote l, as it did two ye ars ago—is increasingly seen as a smart and necessary thing to do among China's capitalists.

Keep that in mind as the big deals get announced on CNBC, and everyone starts wringing their hands. And remember how the Japan hysteria played out: In many cases, Japanese buyers overpaid wildly for assets, making their Western owners richer. There's little reason to think it's not happening again.