Regardless of whether or not Geno Auriemma and his University of Connecticut Huskies win an 11th national championship next Tuesday night in Indianapolis, history has already staked its claim at this year's women's Final Four. This weekend, for the first time since women's basketball began staging national championships 44 years ago, all four coaches in the semifinals will be men. As 1995 Final Four most outstanding player and current ESPN analyst Rebecca Lobo hashtagged in a tweet late Monday evening, #YouveGotMale.

Auriemma, 62, now in his 30th season at UConn, will be joined in Indy by Scott Rueck of Oregon State, Mike Neighbors of Washington and Quentin Hillsman of Syracuse. Whether or not the college athletic sisterhood yearned for an exclusive fraternity, it has one now. "It doesn't bother me that four men are bringing their teams to the Final Four," says former Tennessee guard and ESPN analyst Kara Lawson. "It bothers me that nobody wonders why there aren't any women coaching men's college basketball teams. Or why there are so few women in jobs such as strength coach for a men's team or even athletic director."

As landmark moments in women's athletics go, #YouveGotMale is the antipode of Billie Jean King shaming Bobby Riggs in 1973. It's a clash between Title IX, the federal gender-equity statute that was enacted the same year as the first women's national championship (1972), and the Entitled XY chromosomal group. There have been plenty of women's Final Fours without the Tar Heels of North Carolina, but there has never been one without a pair of heels pacing the sidelines. "It's a disturbing trend," says Lawson, who played for the most towering female figure in the history of women's basketball, Pat Summitt, at Tennessee. "Why is it so easy to hand over a woman's program to a male?"

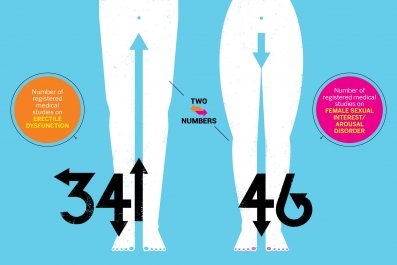

And why is women's basketball the only popular Division I sport in which the majority of head coaches are female? According to the website fivethirtyeight.com, 58.6 percent of the head coaches in Division I women's basketball last year were female (as opposed to women's soccer, for example, where the figure was 26.5 percent). Five years ago, that number was 66 percent. Of course, 0.0 percent of the head coaches in Division I men's basketball last year, or in any year, were female.

"There is a slow and steady decline in the number of female coaches across not just basketball but all sports," says Danielle Donehew, the executive director of the Women's Basketball Coaches Association (WBCA). "That data is evident. It's important to acknowledge our concern for that. We're committed to working to reverse the trend."

The irony is that Title IX was installed to provide women more opportunities in intercollegiate athletics, and it has—as participants. In the four-plus decades since the passing of Title IX, the growth in female participation in both youth and intercollegiate sports has grown exponentially. In 1971, i.e., one year before the passage of Title IX, just one in 27 girls participated in high school sports, according to the Women's Sports Foundation. By 2008, that number was one in two.

Forty-four years of steadily increasing participation in women's sports should have yielded a dramatically expanded pool of female head coaching candidates to fill the concomitantly growing number of jobs in women's collegiate sports. So how come males are encroaching on women's head coaching jobs at the Division I level like never before?

"I don't like to deal in generalizations," says Lawson, who has played for both men and women during her 13-year WNBA career. "Every individual school makes its own decision, and every athletic director will give you a different answer. I do like facts, though, and the facts are that an overwhelming majority of Division I athletic directors are male."

Lawson is correct. According to NCAA statistics released last September, only 37 of 313 Division I athletic directors, or 11.8 percent, are women. That may or may not play a role in the fact that two of the four head coaches at this weekend's Final Four—Pac-12 ambassadors Neighbors and Rueck—never played college basketball. Auriemma played briefly at West Chester (Pennsylvania) University and Hillsman, the first African-American male to lead a program to the women's Final Four, played at Division III St. Mary's College of Maryland.

"It doesn't surprise me," says Lawson, who played in three Final Fours. "As a woman, you have to be overqualified to be considered."

When Oregon State defeated Baylor 60-57 on Monday night in the Dallas Regional final, it marked Rueck's and the school's first trip to the women's Final Four. Rueck, an alumnus of Oregon State, never played for the Beavers.

Rueck's counterpart on Monday night, Baylor's Kim Mulkey, led Louisiana Tech to a pair of national championships as a player in 1981 and '82. She served as an assistant at Tech for 15 years under Leon Barmore, the first man to guide a women's team to the national championship (1988). When Barmore decided to retire after the 2000 season, Louisiana Tech made Mulkey what she considered to be an insulting offer, so she made her exodus to Waco (and Barmore stayed on in Ruston for a few more seasons before eventually become Mulkey's assistant at Baylor).

Mulkey has since led the Bears, previously a cipher in the oligarchical realm of women's college hoops, to a pair of national championships, including a 40-0 season in 2012. "I know I've never worried about how good a player my coach was or their gender," says Lawson. "I only cared if they knew what they were doing. What baffles me is how there are no women on men's coaching staffs. In any workplace, how do you expect to have a successful team when you eliminate 50 percent of the possible workforce from consideration without even examining if they're qualified?"

Every trend in women's college basketball the past quarter century has been shaped by the Auriemma-Summitt dynamic, and that includes male coaching creep. On January 16, 1995, Martin Luther King Day, Connecticut and Tennessee played for the first time, in Storrs, Connecticut. The top-ranked Lady Vols were the game's established vanguard, winners of three of the past eight national titles. The No. 2 Huskies, led by Auriemma, then a brash young male coach with matinee-idol looks, were the upstarts.

The game was serendipitously timed. Michael Jordan was in the second year of his NBA hiatus. Major League Baseball was in the midst of its longest strike in history and the NHL had just ended its 3-month lockout five days earlier. The sports landscape was barren: Auriemma and his charismatic team, led by Lobo, were a welcome splash of color on a bleak sports canvas. UConn 77, Tennessee 66 was not the first televised game in women's college basketball history. It was just the first one that any casual fan could remember.

Connecticut versus Tennessee quickly blossomed into a national rivalry. As much as the dominance of the two programs, winners of 15 of 21 national championships since that MLK Day, the genuine friction between Auriemma and Summitt fueled the rivalry. Here were two coaches with almost nothing in common beyond their absurd win percentages (Auriemma, .877, 10 national championships; Summitt, .841, eight national title). One of them, Geno, relished the opportunity to crack wise about his nemesis. "They're the Evil Empire," he once said of Tennessee.

The animus bred television ratings for ESPN and a magnificent windfall at UConn, where women's basketball always plays to sold-out arenas, either at 10,167-seat Gampel Pavilion on campus or the 16,294-seat XL Center in Hartford. How many athletic directors coast to coast have tuned into a UConn game in the past two decades, observed the passionate support of Huskies fans and the exquisite play of the team and wondered, Is there another Geno Auriemma out there?

Meanwhile, as coaches' salaries increased, thanks in no small part to the runaway success of Connecticut's and Tennessee's programs, more male coaches submitted their resumes for women's jobs. "As the money got bigger, the jobs became more prized," says Lawson. "And in turn, those jobs got tougher to keep. There's a lot more turnover in women's coaching than there used to be because it's now supposed to be a revenue sport."

To be fair, there have long been and still are more males seeking careers in coaching than females. The competition for jobs in men's basketball is particularly fierce, particularly if you are a man with limited or no college playing experience. Auriemma, whose team is currently on a 73-game win streak (not to be confused with a previous 90-game win streak) only pursued a career in women's basketball after realizing how limited the opportunities were for a 5-foot-9-inch Italian immigrant who had never gotten off the bench for his college team.

"Athletic directors are always going to pick a coach that fits their culture," says Donehew. "Or maybe it's someone from that community, or who has a style of play that they like. There are a lot of traits besides gender."

Perhaps, but if 88 percent of Division I athletic directors were women instead of men, how many more women would be Division I head basketball coaches? "That's an interesting question," admits Donehew. "We are of the opinion at the WBCA that young men and women benefit from having both men and women as mentors, as coaches. As teachers."

A few years ago the WBCA launched an annual two-day seminar for its head coaches and assistant coaches to help them become more savvy. "It's called the 'Center for Coaching Excellence'," says Donehew. "It's not about X's and O's. It's about the business side of coaching basketball at this level and how to succeed in that aspect of your job."

The seminar is open to both male and female coaches in women's basketball, but it may prove most valuable to young female assistant coaches hoping to one day interview for the job of CEO of a Division I program. Most likely an interview conducted before a male athletic director. "The Center for Coaching Excellence has been around six or seven years and is one of our most popular programs," says Donehew. "What's interesting is that the initial funding for it came from a grant from the NCAA—and a donation from Geno Auriemma."