If you haven't read Hebrew since the rite-of-passage ceremony known as the bar mitzvah, customarily conducted at the age of 13, then a willfully obscure text of ancient Jewish mysticism is probably not the best means to reacquaint yourself with the language of the Old Testament. Yet there I was in a Northern California synagogue, trying to remember my alefs and daleds, less out of the famous guilt of my tribe than a curiosity about that text—the Zohar—and, more specifically, about the man who has done more than any other alive today to unlock its secrets.

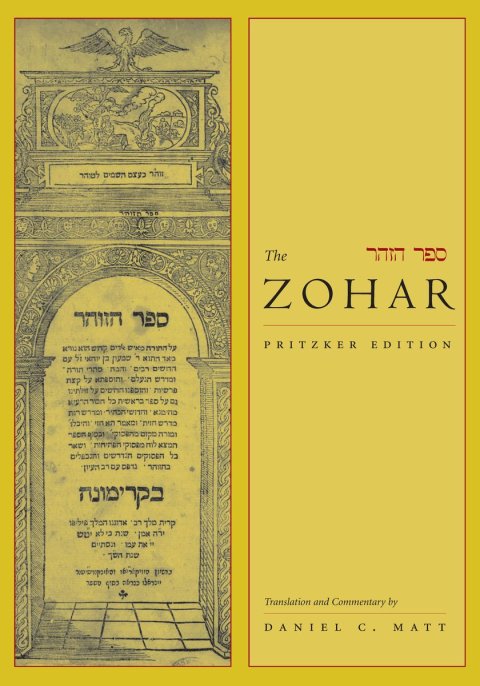

Each month, the scholar of Jewish mysticism Daniel Matt holds a study session on the Zohar, among the most beautiful yet impenetrable works of Jewish spirituality. Matt's authority on the subject is unrivaled: He is the only person to have translated the entirety of the Zohar into English. The effort spanned two decades and ran to 12 volumes (he had help on the last three). When I visited him in May at his house in Berkeley, California, the last of these had just been published. "For the English-speaking world, the Zohar's gates are now opening even wider," declared Judy Silber on NPR.

Thus on a Wednesday afternoon in mid-April, I walked with no small amount of trepidation into a sunlit room at the Congregation Beth El synagogue in Berkeley, not far from where Matt has spent years working on the Zohar, in a studio overlooking the glorious hills of the East Bay. Most of those in attendance were rabbis; one was a psychotherapist; all could read Aramaic (the ancient language related to Hebrew), or at least Hebrew itself, and were becoming fluent in the Zohar.

The session began with song. There followed a prolonged period of silent meditation, during which you could hear the occasional shouts of a child from the courtyard of the adjacent nursery school. There were crackers and cheese, as well as instant coffee.

'Mystical Jewish Bible'

The Zohar—central to the mystical strain of Judaism known as Kabbalah—is a 13th-century commentary primarily on the first five books of the Bible, known as the Torah. That might make it sound dull; it is anything but. Imagine the Old Testament as written by H.P. Lovecraft, Bible stories tripping on acid, rendered in difficult-to-decipher Aramaic, full of wisdom and beauty but shrouded in obscurity, a 1,900-page text written more than 700 years ago whose teachings have been embraced by celebrities like Madonna but not fully understood even by most scholars of Judaism.

The Zohar serves as "the ur-text of the mystical Jewish imagination," explains Shaul Magid, the Jay and Jeanie Schottenstein professor at Indiana University, where he teaches Jewish and religious studies. Magid calls it a "kind of 'mystical Jewish Bible,' refracting the Hebrew Bible through its particular cosmological lens," which includes a complex schema of 10 dimensions, or sefirot, that constitute reality. Some have even compared the cosmology of the Zohar to the conception of the universe suggested by quantum physics, string theory in particular.

Not to sound like a late-night television salesman, but, well, there's more. The Zohar is also a masterwork of medieval literature, but much less known than its counterparts, partly because previous translations have been imperfect or incomplete. Almost singlehandedly, Matt has made the Zohar available to the public. It took him about as long as it did Saint Jerome to translate the Bible from the Hebrew into Latin 1,600 years ago.

RELATED: The battle for the soul of Los Angeles

Part of the joy of delving into the Zohar, I suspect, is that you can't run it through Google Translate, at least not if you want a halfway coherent result. It isn't the dull bar mitzvah passage you were forced to memorize when you would much rather have been watching television. Nor is it the kind of cheap spirituality that makes for a warming flash of faith on an otherwise dull February night. Even if you're not Jewish, even if you believe in no God at all, the Zohar is a reminder that faith is difficult work, frequently frustrating but deeply rewarding to those who persevere. That reminder is acutely necessary today, an age in which so many charlatans have passed themselves off as prophets.

"This is a particularly dense passage," Matt announced when the meditation was through. The passage in question was from the fourth volume of his Zohar, a commentary on Exodus 14, in which God parts the Red Sea for the Jews fleeing Egypt. It was an especially germane selection because Passover had just concluded, marking the end of a difficult season in which synagogues and Jewish centers around the country faced bomb threats. The Zohar, composed in Spain 700 years ago, spoke to the travails of the Jews, which must have seemed endless even all those centuries ago.

Feeling increasingly nervous about my impending confrontation with the Zohar, I went for more instant coffee. Everyone else was ready, surgeons on the cusp of beginning an incredibly intricate procedure.

In keeping with the Zohar's elusive quality, the text Matt had chosen wandered from one beautiful image to another, never lingering too long. "You might be wondering," Matt eventually said, "what does this have to do with crossing the Red Sea?" He later estimated that about 5 percent of the Zohar is purposefully opaque, as impenetrable as the passage we were studying.

Then again, mysticism is less about understanding than experience. Because I haven't studied Hebrew in many years, I quickly lost all hope of trying to keep up with the class. And it was only when I surrendered to the incomprehensibility of the Zohar that I began to understand it. Later, I remembered what Matt had told me in his study overlooking the Berkeley Hills: "You have to be overwhelmed by it. Unless you're willing to be overwhelmed by it, you're not getting the message."

Nor is there any one message to get, some sentiment that might fit onto a bumper sticker. The Zohar is not for people who have bumper stickers (disclosure: I have bumper stickers, but they're really old). During a break in Matt's lesson, one of the rabbis revealed that she'd written a rock song based on the Zohar. She sang a couple of lines in a lovely, clear voice:

You took me through fields

where the straw grows high

We lay on our backs

Eyes to the sky

The song is called "Come on, Lover." ( It is available on Bandcamp.)

In the age of information, it is immensely refreshing to know that not all that can be known can be Googled, that some kinds of wisdom cannot be conveyed through social sharing. In a world flattened by the internet, the Zohar remains a mountain, one that beguiles because, as George Mallory said of Everest, it's there.

"As morning is about to lighten," says the Zohar passage we were studying in the Berkeley synagogue, "light darkens and blackens; blackness prevails. Then a woman unites with her husband, conversing with him, entering his palace. Later, when the sun is about to set, it brightens, and night comes and absorbs it. Then all gates are closed, donkeys tremble, and dogs bark."

There is so much to love here. There is, for example, the way the light "darkens and blackens" as morning comes; the way "blackens" turns into "blackness"; the domesticity of "a woman unites with her husband," but then the grandeur that comes with the discovery that their union takes place in a palace. Morning seems to be on its way, but "night comes and absorbs it." And what about that returning night has driven the animals mad?

We can't say. We don't need to. Matt explained that the passage is about hope, about the turning of every night into day. His explanation made me think of the words of another Jewish prophet, Bob Dylan: "They say the darkest hour is right before the dawn."

Poet and a Translator

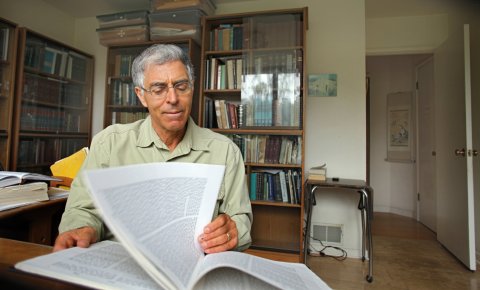

A mild-mannered, olive-skinned man in his mid-60s, Daniel Matt looks like he might teach graduate-level math or offer couples counseling in his cozy house, full of sunlight and books, in the hills above Berkeley. His glasses are large, his smile gentle. Little about his manner or appearance suggests he has just completed a grueling intellectual feat that consumed nearly two decades of his life.

There is, however, a single hint. It sits in his driveway on a champagne-colored, four-door sedan, showing the kind of wear you'd expect from a 14-year-old car. The car's plates, though, are unusual, bearing a single word, which points to his decades-long obsession: "Zohar," it says.

In 1995, Matt was contacted by Margot Pritzker, the Chicago philanthropist whose family owns the Hyatt hotel chain. For the previous four years, Pritzker had been intensely studying Judaism with Rabbi Yehiel Poupko, a scholar at the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago. She wanted to go deeper into the Zohar, but she didn't read Aramaic, and the only available translations were pale shadows of the original. So Pritzker called Arthur Green, a scholar of Jewish mysticism at Brandeis University in Boston, and asked if he knew anyone who'd take on the work of translating the entirety of the Zohar from ancient Aramaic.

Pritzker tells me Green gave her three names: "Daniel Matt, Daniel Matt and Daniel Matt." Matt had been a student at Brandeis in the 1970s. Since 1979, he'd been teaching at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, where he was a scholar of Jewish mysticism.

Though previous generations of Jews had endowed the Zohar with what historian Boaz Huss calls "an authoritative and sacred status," modernity had driven an increasingly urbane and sophisticated Jewish diaspora to reject the more obscure aspects of its faith. "Jews threw out, along with the superstition and the supernatural, a lot of the powerful spiritual teachings," Matt laments.

RELATED: School segregation is getting worse

That's in large part because the kind of Judaism most Americans are familiar with today has its roots in Germany, whose Jewish population "wanted to prove that Judaism was ethical and rational," explains Susannah Heschel, the chair of the Jewish studies department at Dartmouth College. They sought to "Protestantize" their religion, Heschel says, in part by rejecting what they saw as embarrassing shows of piety by their Eastern European brethren.

If decades passed without someone attempting an English translation of the Zohar, it may well have been because few wanted one. The desire to become more Western was predicated on the need to become less mystical.

A backlash was inevitable, just as it seemed that Jews had fully assimilated into American society. "American Jewish life is in danger of disappearing, just as most American Jews have achieved everything we ever wanted," the celebrity lawyer Alan Dershowitz complained in a 1997 book titled, unsubtly, The Vanishing American Jew. Plainly, a return to the Zohar suggested that Jews did want something more than widespread acceptance into the Ivy League.

When Pritzker proposed the project, Matt refused. "He thought I was crazy, that this can't be done," she says. Eventually, he agreed to spend a month on a trial run of sorts, only to come away convinced that translating the entirety of the Zohar would be an insane undertaking. Pritzker asked him to come to Chicago and give his refusal in person. Once there, he continued to protest that "this was not possible," Pritzker recalls. "This would take a lifetime."

"I've got time," she told him, and Matt ultimately concluded that he did too. She agreed to sponsor his work through the Pritzker Family Philanthropic Fund, a charity whose tax filings for 2015 show assets of $160 million. That allowed Matt to quit teaching and devote himself fully to the Zohar, on which he estimates he spent about seven or eight hours daily for the last 18 years.

At first, he wasn't able to translate more than 11 lines per day. Part of the problem is that while there are authoritative editions, there is no single definitive one. "Before I could begin to translate any individual page, I reconstructed the Aramaic text, based on Zohar manuscripts that are strewn about numerous European libraries," Matt tells me. "Also, I had to work painstakingly in order to convey in English the lyrical quality of the original Aramaic."

Eventually, Matt increased his speed to 40 lines per day, but his task remained unimaginably vast. Alan Harvey, the editorial director of Stanford University Press, says he feared Matt might not finish the project, especially after the first several volumes were published. He credits Poupko with providing Matt with the motivation to keep going.

"When you read the text, you can see Daniel growing with the text," Pritzker says. "He is a poet, as well as a great translator."

For the lay reader, Jewish or not, the poetry of the Zohar is the main attraction, as when the rabbis discuss the demonic realm, or "the Other Side" (Sitra Ahra in Hebrew): "Chieftains, masters of fiery sparks, roam and descend, strike and ascend. Entering the Hollow of the Great Abyss, their sparks are dyed red, flaming fire fused to them. Embers shoot out—flying, descending, assaulting human beings."

Reading these words, you can't be surprised that Leonard Cohen was a student of the Zohar, given the surrealistic, darkly apocalyptic bent of his lyrics. The Jewish-Canadian singer, who died last year, studied Matt's text with Rabbi Mordecai Finley of the Ohr HaTorah Synagogue in Los Angeles.

"It's something that's going to stand as long as people speak English," Finley says of Matt's translation. "It's monumental."

'God Needs Us'

The Pritzker Zohar has been published by Stanford in hardbound, mustard-colored editions. The color put me in mind, oddly enough, of the parable of the mustard seed in Matthew 17:20, which invokes, like the Zohar, the immensity of belief when wielded by the righteous believer: "If ye have faith as a grain of mustard seed, ye shall say unto this mountain, Remove hence to yonder place; and it shall remove."

Harvey, who published the Pritzker Zohar, says about 70,000 volumes have been sold in all. It's less clear how many people have bought all 12 volumes together, which would cost $785, by Harvey's count.

Yet to discount Matt's work as merely an achievement of academic endurance, one bound to languish in college libraries, is to miss its implications for American spirituality, particularly the oddly progressive cast of this ancient work.

In welcome contrast to most religious texts, with their domineering male gods, the Zohar introduces the Shekhinah, a female aspect of divinity just as important as her male counterpart; one of Shekhinah's names is also "secret of the possible."

If the Zohar demands shows of faith, it is through the doing of good deeds. That will, the Zohar claims, restore order by uniting the male and female halves of God. Matt says to think of our actions on Earth as a kind of "aphrodisiac" for the divine pair. At a time when all three Abrahamic faiths are struggling with their versions of fundamentalism, Matt's work is a reminder that religious faith, at its best, is about repairing the world, not enforcing dogma; it's about the beguiling mysteries of existence, not its certitudes.

"God needs us," Matt says. "God is incomplete without our active participation in mending the world."

The Zohar's final volume arrives at a time when world religion seems increasingly removed from the kind of private, contemplative spirituality evoked by the Zohar (the last three volumes were translated by Nathan Wolski and Joel Hecker). The Islamic State militant group posts beheadings on YouTube, American evangelicals forsake their Christian convictions for short-term political gains, Jewish settlers in the West Bank take land away from their Palestinian neighbors. In India earlier this spring, Hindus killed a Muslim man who was transporting cows, an animal considered sacred in Hinduism. Whoever your god or gods are, they cannot have had this in mind.

In an age of extremism, Matt's work is a rejoinder that calls for humility, patience and wonderment. This has long been an animating theme. "We have lost our myth," Matt wrote in his 1996 book, God & the Big Bang: Discovering Harmony Between Science & Spirituality. "Many people have shed the security of traditional belief…. If they believe in anything, perhaps it's science and technology. And what does science provide in exchange for this belief? Progress in every field except for one: the ultimate meaning of life."

That sentiment contains an echo of the rationale Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers had given a century before. A British occultist, Mathers was the first to translate the Zohar into English, though he worked from the Latin, not the original Aramaic. He did so because he "opposed institutionalized Christianity, and hoped for a spiritual Christian revolution," according to Kabbalah historian Boaz Huss. Mathers offered a ferocious explanation for why he was taking on the task of translating the Zohar:

I say fearlessly to the fanatics and bigots of the present day: You have cast down the Sublime and Infinite one from His throne, and in His stead have placed the demon of unbalanced force; you have substituted a deity of disorder and of jealousy for a God of order and love; you have perverted the teaching of the crucified One.

Though it may be a work of faith, the Zohar's main goal is to instill awe. That alone makes it indispensable. However, the Zohar's mystical overtures can also make it the victim of spiritual fads.

Oops, I Was Mystical Again

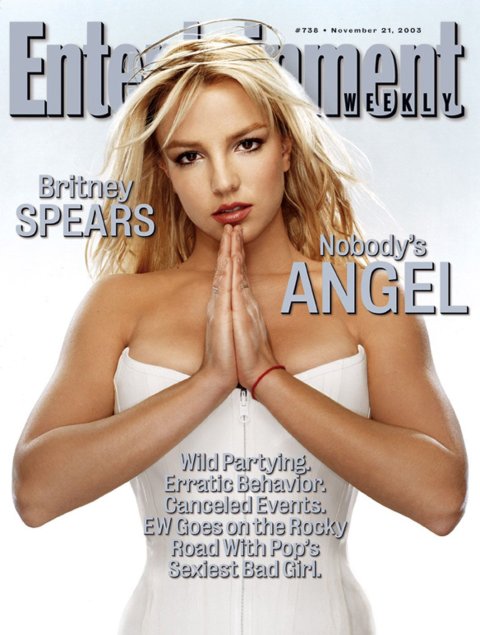

In 2003, the singer Britney Spears appeared on the cover of Entertainment Weekly, wearing a white dress and clasping her hands in prayer, a play on the cover line: "Nobody's Angel." On her left wrist is plainly visible a red string. The red string, which was becoming a popular accessory in Hollywood and elsewhere, came from the Kabbalah Centre, which explained that it is a talisman out of the Zohar that "protects us from conscious & unconscious stares." (It can be purchased from the Kabbalah Centre for $26.)

Kabbalah is the spiritual practice based on the study of the Zohar, though it emerged somewhat before the text. Kabbalah calls for a solitary, mystical experience of God, originated in what is today the French region of Provence in the 12th century. Kabbalist rabbis there probably practiced a form of meditation, focusing their minds on the four letters that constitute God's name in Hebrew (YHWH, for Yahweh). Although they were rebels, these rabbis were also traditionalists who sought to restore the immediacy of religious experience, which they argued was lost in the heavily regulated space of the synagogue.

The essential elements of Kabbalah were popularized in Eastern Europe in the 18th century, by the revivalist, mystical Jewish movement known as Hasidism. The paintings of Marc Chagall, with their surrealistic evocations of shtetl life in the early 20th century, are thought by many to reflect the Kabbalistic understanding of the world prevalent in the villages of Eastern Europe where Hasidism was born.

The greatest proponent of Kabbalah in the 20th century was Gershom Scholem, the German-Jewish scholar nearly contemporaneous with Chagall. Scholem rebelled against the Germanic strictures of his faith, says Heschel. He also popularized the Zohar by showing that it was "not some weird aberration, but very much at the center of Judaism."

The writer George Prochnik, who recently published a biography of Scholem, has written that Scholem believed that "the authors of the great works of Kabbalah had undertaken a profound, creative engagement with the historical tragedies of Jewish history in exile. Kabbalah, from his perspective, was, indeed, nothing less than a kind of mythological key to understanding human misery in general, and the Jewish expulsion from Jerusalem and then Spain in particular."

Kabbalah's most recent rise to prominence did not come about as a result of rabbinical endorsement but from a far less likely source: Hollywood. As with that other spiritual movement beloved of celebrities and based in Los Angeles—the Church of Scientology—the modern iteration of Kabbalism has been derided as little more than a money-making cult.

The Kabbalah Centre's headquarters are in an undistinguished, mission-style building on an even more undistinguished corner of Robertson Boulevard, in a part of Los Angeles that is home to many religious Jews. Across the street is a squat office building, where the Kabbalah Centre's publishing arm produces titles like The Power to Change Everything; Kabbalah on Sex: Make Love, Make Light (New Edition); The Monster Is Real; The Power of Kabbalah for Teens and Rebooting: Defeating Depression With the Power of the Kabbalah.

The vast majority of these books were written by Karen and Philip Berg, who started the Kabbalah Centre, or by their sons Yehuda and Michael. In 1965, Philip started the National Research Institute of Kabbalah in New York City. It was his entrepreneurial second wife, Karen, however, who understood that Jewish mysticism could, if marketed correctly, play right into a New Age curiosity about the occult.

They opened the Kabbalah Centre in Los Angeles in 1984. From the start, the Bergs grasped that they would be successful only if they distilled the teachings of the Zohar into simplistic lessons with a self-help bent. Sometimes, that has bordered on shamanism: During my visit to the Kabbalah Centre, I was handed an abbreviated pocket edition of the Zohar and told to keep it on my person at all times, as it could, like the red string, ward off evil. Also on sale in the spacious, well-stocked store was Kabbalah Water, which is supposed to have healing powers. (It comes from Canada.)

Celebrities flocked to the Kabbalah Centre in the mid-1990s, starting with Sandra Bernhard in 1995—just as Matt was about to begin his own extended affair with the Zohar. It offered them a sheen of spiritual seriousness, promised holistic renewal and didn't require a lot of work. Even if the Bergs were shunned as unserious (or dangerous) by mainstream Judaism, celebrities gave them far more cachet than any rabbinical organization ever could. Madonna started attending in 1997; as the Los Angeles Times reported in 2011, "The center's assets grew from $20 million in 1998...to more than $260 million by 2009," buoyed by membership dues and aggressive merchandising, like the red strings that became a must-have accessory on the West Side of Los Angeles.

Green, who knew Matt at Brandeis University, is far more willing than Matt himself to criticize the Kabbalah Centre and what he sees as its sleekly packaged spirituality. In a 2004 interview with Fresh Air host Terry Gross, Green expressed dismay at what was then a rising tide of celebrity Kabbalism. "Most of the people involved in this pop practice have little idea of what Kabbalah is really about and have little appreciation of the profundity of it."

To detractors, the red strings and related merchandise are examples of cultural appropriation, even if they precede by many years that phrase now beloved by the social justice warriors of social media. The model of Scandinavian origin with hair in dreadlocks is a cultural relative of the actor who, red string proudly wound around wrist, proclaims his profound affection for Kabbalah as he returns from a boozy Ibiza weekend. Of course, the Kabbalah Centre has its defenders, who can point to the Bergs' commercial savvy as a kind of proselytizing. A faith closed to the curiosity of outsiders is a faith bound to die.

I don't get the sense that Matt cares one way or another about which celebrities decide to adopt Kabbalah over pilates. His sole concern is the text of the Zohar itself. On this count, however, he does not believe the Kabbalah Centre adequately acquits itself. When I visited him in his study, Matt took me through a passage he called a "radical reading" of Genesis, with a subversive quality his translation highlights: "With this beginning, the unknown concealed one created the palace. This palace is called Elohim, God. The secret is: With beginning, _____ created God."

By making God the object of this formulation, the Zohar suggests that there was some primal divine power beyond what we call "God." "What we conceive of as God is secondary to the boundless reality of God," Matt explained. In the place of certainty, Zohar offered mystery.

In the Kabbalah Centre's Zohar, the astounding conclusion is translated with utter conventionality, God doing the usual, expected business of creation: "In the beginning Elohim created." All of the mystery is gone.

'A Spark of Impenetrable Darkness'

The Zohar's Hebrew name is sometimes translated to "Book of Splendor." It was written in the 13th century, largely by a Spanish rabbi named Moses de León, who tried to present it as a second-century work by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his colleagues, thus hoping to gain legitimacy from Kabbalists and others who would presumably be impressed by the Zohar's historic provenance.

"It's a medieval experiment in fiction," Matt says. "We find rabbis wandering in the Galilee," encountering colorful characters who offer insight and wisdom—for example, a donkey driver who turns out to be much smarter than he appears at first blush. With its "very loose narrative framework," the Zohar isn't truly a work of literary fiction, though Matt has compared it to Dante's Divine Comedy and Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, both written during the medieval period, and to Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote, composed several centuries later.

In fact, the similarities between the Zohar and those canonical works run deep, especially in their conflation of romantic and spiritual quests. Dante made those quests literal, his narrator traversing hell, purgatory and paradise in search of his beloved Beatrice. In the Zohar, the quest is more abstract, its ultimate goal the union of the masculine half of God with his "bride," the Shekhinah.

Often, the Zohar reads like modern poetry, as in this depiction of the creation of the world from Genesis (which Matt renders in verse in an anthology of selections from the Zohar):

A spark of impenetrable darkness flashed

within the concealed of the concealed

from the head of Infinity,

a cluster of vapor forming in formlessness, thrust in a ring,

not white, not black, not red, not green, no color at all.

From the start, the Zohar makes clear that it is not going to be a religious text of straightforward warnings and commands, of easily decipherable parables whose morals can be drilled into children. That is precisely why some have shunned the Zohar, and why others have devoted their lives to it.

And though I can't claim to have become a scholar of Jewish mysticism, a curious thing happened during my attendance at one of Matt's classes: I forgot myself. I forgot President Donald Trump, and the latest Kardashian-Jenner outrage, and the credit card dispute I needed to take care of, and the Brussels sprouts I was supposed to buy. I neither tweeted nor checked email.

As the rabbis around me plunged elbow-deep into the ancient text, it felt that we had become ancient too. Maybe I'd had too much instant coffee, but we seemed for just a moment to turn into a beleaguered tribe of wandering Hebrews, searching for salvation both material and spiritual, wandering through mountain ranges and deserts, looking for home.

I remember that feeling well, in part because I haven't had it since. Was it the experience of God? I'd like to think, rather, that it was the experience of deep reading. That is a religion of its own, as any non-Muslim reading the poetry of Rumi can tell you.

"The Zohar plunges you right into a world beyond this world," says Dartmouth professor Heschel.

Yet for all its notorious obscurity, the Zohar is decidedly universal in its themes. Its language is complex, but its lessons are simple, as true for Rabbi Shimon as for Madonna, as true in the Berkeley Hills as in the hills of Galilee and the mountains between France and Spain, where a scribe seven centuries ago decided he would go off to find God on his own.