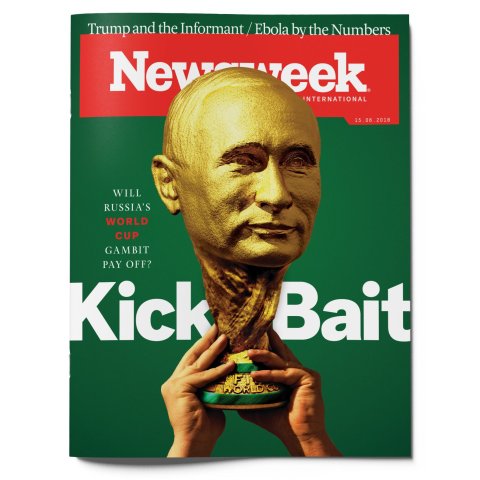

Vladimir Putin kept a watchful eye on a black-and-white soccer ball as it soared toward him through a spacious Kremlin office, before he deftly bumped it back with his head. On the other side of the room, Gianni Infantino, the president of FIFA, soccer's international governing body, waited for the return pass. When it came, he flicked the ball up, juggling it from foot to foot before kicking it back to the Russian president. The two men, both dressed in suits and ties, were taking part in a promotional video for this summer's World Cup, which Russia will host for the first time.

In May, just weeks after the filming of the video, Putin and Infantino met again, this time in Sochi, on Russia's Black Sea coastline, where they inspected the Fisht Olympic Stadium. The 48,000-seat arena is one of a dozen that Russia has either built or revamped for the tournament, which runs June 14 to July 15 and takes place in 11 cities. The government says it has spent almost $12 billion on the tournament, not including some spending on infrastructure. Some independent estimates say the true figure could be billions of dollars higher, making this one of the most expensive World Cups ever.

This massive spending isn't because Putin is a huge soccer fan; he isn't particularly interested in it. Instead, some say, he hopes to use the World Cup to improve Russia's international image. That's a difficult task, especially after the Kremlin has been accused of war crimes in Syria and Ukraine, spy poisonings in Britain and election meddling in the United States and other Western countries. But Putin couldn't have chosen a better platform to spread his message: The tournament is the world's most-watched sporting event.

"Putin wants to present Russia as a strong country—not just in the military sense—that is able to organize events well on an international level," says Andrei Kolesnikov, a political analyst at the Carnegie Moscow Center, a Russian-based think tank. "The World Cup will also be an attempt to soften his iron man reputation."

The Kremlin has a long history of using international sporting events for propaganda purposes. For decades, the Soviet Union promoted its athletes' success at the Olympic Games as proof of the socialist system's supposed superiorities. Some of these efforts were benign, others more sinister. Just before the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, for instance, Soviet authorities rounded up dissidents, handicapped people and others they judged to be "undesirables," forcing them out of the city for the duration of the games.

Decades later, Putin put a modern-day spin on Communist-era propaganda when Russia hosted the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014. The Kremlin pumped billions of dollars (no one knows quite how much) into the games—widely reported to be one of the most expensive Olympics of all time. Opposition politicians slammed what they said was massive Kremlin corruption. But Putin hailed Sochi as a showcase for the "new" Russia that had emerged after the collapse of the USSR.

It worked. Russia's athletes topped the medals table, the world's media praised the Olympics' opening and closing ceremonies, and despite some negative coverage in the lead-up to the event, Russia basked in the glow of positive press. The country's Federal Security Service, or FSB, also celebrated what it said was a joint operation with the United States and other Western countries to avert planned attacks by Islamist militants. Even subsequent allegations of massive, Kremlin-sponsored doping failed to diminish the results, at least as far as most Russians were concerned.

Now, as the world's top soccer players and an estimated 600,000 foreign tourists head to Russia for the 2018 World Cup, Putin is hoping for a similar success. "This was the dream of many generations, and this moment is about to happen," Arkady Dvorkovich, head of the Local Organizing Committee for Russia's World Cup, said on May 30. "The Olympics in Sochi demonstrated how we can welcome guests, but this situation is much larger on the global scale."

Yet with that scale comes greater risks and more potential problems, from Islamist militant attacks to human rights abuses. And the Kremlin is doing everything it can to ensure nothing goes awry.

'Your Blood Will Fill the Stadium'

The jihadi fighter thrusts an automatic weapon into the air as a bomb explodes nearby, shrouding a World Cup stadium in plumes of white smoke. In the background, the Russian president stands at a podium, in the crosshairs of a sniper's rifle. "Putin: You disbeliever, you will pay the price for killing Muslims," reads the message on this online poster, which was produced in April by supporters of the Islamic State group (ISIS). In other gruesome images circulated online, jihadis are depicted beheading some of the world's top soccer stars, including Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo. A caption reads, "Your blood will fill the stadium."

Over the past year or so, ISIS has suffered crippling military defeats in Iraq and Syria. But the jihadi group has been using social media and encrypted messaging services to encourage followers to target spectators at the World Cup. Analysts say that security at the stadiums will be tight but that crowded fan zones around the arenas will be far harder to lock down and could be vulnerable to ISIS-inspired "lone wolf" attacks. Such assaults, which require minimal planning, have taken place in London and Manchester in England, Barcelona in Spain and in Russia, killing dozens of people.

Just because ISIS says it will wreak havoc at the World Cup doesn't mean it will, but security analysts worry the event may be too attractive a target for ISIS militants to resist—especially given the group's loss of territory. "A successful attack [in Russia] would provide a tremendous propaganda boost for the Islamic State and its fighters and supporters," says Matthew Henman, head of Jane's Terrorism and Insurgency Center at the London-based IHS Markit analysis company, in a recent report.

One of the main risks: battle-hardened Russian jihadis with experience creating improvised explosive devices who have returned home from Syria and Iraq. According to Russian security officials, around 4,000 Russian citizens, mainly from the country's North Caucasus region, which includes Chechnya, have fought alongside ISIS in the Middle East.

Although Islamist attacks in Russia have their roots in the volatile North Caucasus, fighters loyal to ISIS have the ability to strike far beyond the area. One World Cup host city at risk is Nizhny Novgorod, just 250 miles from Moscow. On May 4, an ISIS militant wounded three police officers during a shoot-out there. The jihadi fighter was killed by security services after barricading himself in an apartment just 9 miles from the stadium where nations such as Argentina, England and Sweden are due to play. In February and last November, Russian security forces also shot dead ISIS militants plotting attacks in the city.

World Cup host cities in Russia's south are also at risk, says Grigory Shvedov, chief editor of the Caucasian Knot online news agency, which monitors Islamist militant activity in Russia. Shvedov says recent ISIS attacks on Russian Orthodox Churches in the North Caucasus indicate that the jihadi group is gearing up to attack sensitive targets. Volgograd, which borders the North Caucasus region, is a particular security concern. Last November, two police officers were hospitalized with stab wounds after an ISIS-inspired assault in the southern Russian region, which will host matches involving Russia and Spain, as well as Saudi Arabia and Iran. Four years earlier, in December 2013, twin suicide bombings by Islamist militants killed 34 people in Volgograd. Those attacks were carried out by the Caucasus Emirate, a now-defunct jihadi group whose former members have since sworn allegiance to ISIS.

Because of these potential threats, the Kremlin is stepping up its counterterrorism operations. State security services "liquidated" 12 militant cells and arrested 189 suspects between January and April of this year, says Alexander Bortnikov, head of the FSB. The FSB has also ordered chemical plants and other high-risk factories to be shut down during the monthlong event.

Russian security officials insist, however, that the tournament will proceed safely, pointing to their success in preventing attacks on the 2014 Winter Olympics. But there are some crucial major differences between Sochi and the World Cup. "The Sochi Olympics took place at a time when Islamic State was not active in Russia," Shvedov says. "Today, unfortunately, it is extremely active, especially in the North Caucasus region."

ISIS did not claim its first attack in Russia until 2015, when it targeted a tourist site in the country's south, killing one person. Since then, the group has taken responsibility for a series of bombings and shootings, including 20 in the North Caucasus, according to Caucasian Knot.

The World Cup also presents jihadis with a larger number of potential targets than the Sochi Olympics, says Mark Galeotti, an expert on the Russian security services at the Institute of International Relations in Prague. "Sochi was essentially a single securable point," he says. "But at the World Cup there will be too many people, at too many sites. If anyone wants to make a terrorist attack, you don't need to hit a stadium, you just need to hit, say, a bus depot near a stadium. And suddenly that becomes an attack on the World Cup."

'Stalinist-Era Show Trials'

Jihadis aren't the only ones hoping to use the World Cup to advance their cause. As the tournament approaches, Putin's critics are hoping to put a global spotlight on what they call widespread human rights abuses, including state-sponsored violence against political opponents.

The Kremlin appears to be spooked by such plans. In an apparent bid to prevent demonstrations in front of the international press, Russian authorities have banned protests in host cities through July 25. And analysts say the government is doing its best to make sure there is no public dissent even before that law kicks in: Alexei Navalny, the opposition leader, was jailed for a month on May 15 on protest-related charges. Sergei Boyko and Ruslan Shaveddinov, two members of Navalny's anti-corruption organization, were locked up later that month for the same amount of time; Navalny's press secretary, Kira Yarmysh, was handed a 25-day sentence. Their crime? Tweeting about protests.

"The World Cup will be a celebration of Putin's eternal empire of the security services," says Maria Alyokhina, a member of Pussy Riot, the anti-Putin punk band and art collective. "People who come should realize that they are coming to a country where people are beaten at protests, tortured in jail and in police stations, and where there are very many political prisoners."

Among those alleged political prisoners: Oleg Sentsov, a Ukrainian film director. A Russian military court imprisoned him for 20 years in 2015 on terrorism charges, though he says it was just revenge for his opposition to the Kremlin's annexation of Crimea. Sentsov had brought food to Ukrainian soldiers whom Russian troops had blockaded inside their bases during the invasion. Prosecutors said that he and Alexander Kolchenko, his co-defendant, set small fires at the Crimean office of Putin's ruling United Russia party and in the entryway to a Communist Party office. They also accused them of plotting to blow up a statue of Vladimir Lenin in Sevastopol, the Crimean capital. Both men denied the charges.

Critics say the evidence against them was flimsy. The prosecution's main witness withdrew his testimony, saying he had been tortured by investigators into making incriminating statements. The court also dismissed Sentsov's allegations that he had been beaten by security forces, ruling instead that his bruises and scratches were the result of a supposed fondness for sadomasochistic sex. Amnesty International likened the court hearing to "Stalinist-era show trials," while a host of international film directors, including Ken Loach, Mike Leigh and Wim Wenders, signed an open letter to Putin calling for Sentsov's release. Human rights groups say almost 70 Ukrainians are being held in Russia or occupied Crimea on politically motivated charges. The Kremlin insists there are none.

On May 14, a month before the World Cup opening ceremony in Moscow, Sentsov launched an indefinite hunger strike, demanding "the release of all Ukrainian political prisoners held on Russian territory." Other activists are attempting to highlight their causes as well. In May, 14 human rights groups signed an open letter to FIFA, urging it to put pressure on Russia to secure the release of Oyub Titiev, the head of the Memorial human rights organization in Chechnya. Although no matches are taking place in the region, FIFA has approved its capital city, Grozny, as a training base for the Egyptian national team.

Chechen police detained the 60-year-old Titiev in January for allegedly possessing 6 ounces of cannabis. He could now face up to 10 years in prison. His supporters say the charges were trumped up on the orders of officials loyal to Ramzan Kadyrov, the Chechen leader. Apti Alaudinov, the Chechen deputy interior minister, has previously encouraged police officers to frame Kadyrov's "enemies" using similar tactics. "Plant something in their pocket," he said, in comments that were broadcast by Chechen television. Shortly before Titiev's arrest, masked men torched Memorial's office in Ingushetia, a southern Russian republic that neighbors Chechnya. A spokesperson for Kadyrov was unavailable for comment.

Founded in 1989 by Soviet dissidents, Memorial has gained international acclaim for exposing both Soviet-era repression and modern-day abuses. But the human rights group says the catalyst for the current clampdown was probably Kadyrov's loss of his Instagram account this past December. "The closure of his account is a matter of Kadyrov's image," says Oleg Orlov, a Memorial founder. "When he feels offended, nothing else is important to him—whoever gets in his way must be destroyed."

The U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Kadyrov in December over alleged human rights abuses, including involvement in extrajudicial killings. Facebook, which owns Instagram, said the decision meant it was legally obliged to close down his social media accounts, which included threats against Kremlin critics; he had over 3 million followers just on Instagram. "We were held responsible for this by Kadyrov and his inner circle because we are one of the very few sources of information about rights abuses in Chechnya," Orlov says.

FIFA, which only adopted a human rights policy in 2017, says it is concerned about Titiev's arrest but has rejected appeals for it to move its training base from the Chechen capital.

Memorial members hope that international attention on Titiev's case will embarrass Putin into ordering Chechen authorities to release him. Analysts say the former KGB officer is the only person in Russia able to exert any influence on Kadyrov, who often waxes lyrical about his love for the Kremlin leader. "The World Cup is very important for the Kremlin," says Katya Sokirianskaia, who once ran the Memorial office in Chechnya. "If international organizations, especially FIFA, raise the case of Titiev at high levels, then we hope that Putin will intervene and set our colleague free."

Among the Thugs

While some Kremlin critics hope to use the World Cup to highlight their grievances, others want to ruin Putin's tournament altogether by calling for an international boycott of the event. Yet with this month's kickoff, not a single one of the countries due to take part has withdrawn its national team. Even London, which has accused Putin of ordering a hit on Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military intelligence officer who spied for MI6, has balked at missing out on world soccer's biggest competition. (The Kremlin denies the accusations.) Instead of an outright boycott, the British government has refused to send an official delegation to the World Cup. The British royal family is also snubbing the tournament.

So far, only Iceland has joined England in refusing to send a government delegation to Moscow for the World Cup's opening ceremony. And Putin probably isn't concerned. "He is accustomed to bad relations with the West," says Kolesnikov, the Carnegie Moscow Center analyst. "He can get by without delegations. What's important is that the soccer players come."

What's also important is that fans—particularly Russian fans—behave in the stands. In recent years, far-right supporters have unfurled swastikas at stadiums, and in 2010, thousands of soccer hooligans and ultra-nationalists rioted near Red Square after the murder of a fan by a resident of Russia's mainly Muslim North Caucasus region. Russian soccer officials have taken some steps to tackle racism. In 2017, they appointed Alexei Smertin, a former national team captain, as their envoy against discrimination.

But problems remain. In March, Russian fans directed racist chants at France's Ousmane Dembélé, N'Golo Kanté and Paul Pogba during a friendly match against Russia in St. Petersburg. FIFA fined the country $30,000. "Incidents in recent months show how racism is still deeply part of the fan culture in Russia," says Pavel Klymenko, who helps monitor instances of fan discrimination for the Football Against Racism in Europe network.

Likewise, soccer hooligans have gained a terrifying reputation in Russia since going on a rampage during the Euro 2016 tournament in France. But most experts believe security forces will not allow a repeat of such violent scenes; the World Cup is far too important for Putin. Sources within the soccer hooligan scene say the police have been warning known troublemakers they could face long stretches in prison if they do anything to harm the country's international image. (The sources asked for anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter.) "I think they'll prevent trouble at the World Cup," says Vladimir Kozlov, the author of Football Fans: The Past and Present of Russian Hooliganism. "If fans go to Moscow's outskirts looking for adventure, they could get their asses kicked, but that'll have nothing to do with soccer hooliganism."

Home Field Advantage

With all the talk around the tournament of jihadis and geopolitics, it's sometimes easy to forget that this is a sporting event. Russians are excited that the world's top soccer stars will perform in their country, but there is almost zero chance their national team will win. Russia is one of the lowest-ranked squads taking part in the World Cup, and it has not progressed past the event's initial group stages since the collapse of the Soviet Union. "Who are you going to support when Russia gets knocked out?" is a popular joke among soccer fans in Moscow.

The Kremlin can't influence events on the field, but with a little help from FIFA, it is leaving nothing to chance elsewhere. Even the minor details are being taken care of. One example? That promotional video of Putin and Infantino, the FIFA president, kicking a ball around. While Infantino's soccer skills were impressive, some suggested that clever video editing had greatly exaggerated Putin's abilities. (FIFA did not respond to a request for comment about the video.)

"This is all about proving to the world that Russia can stage successfully an event of this magnitude," says Viktor Shenderovich, a well-known Russian writer and soccer fan. "The soccer is of secondary importance. For Putin, the propaganda comes first."