About three years ago, not long after Donald Trump announced his improbable bid for the White House, Felix Sater sensed a big opportunity. He and his childhood friend, Michael Cohen—then a lawyer and dealmaker for the Trump Organization—had been working for more than a decade, on and off, to build a Trump Tower in Moscow. The New York real estate mogul had long wanted to see his name on a glitzy building in the Russian capital, but the project had never materialized.

Now, with Trump running for office, the timing seemed right to Sater, who felt he had the proper connections for the project. A Moscow native whose family had fled to Brooklyn in the 1970s, he had returned to Russia in the 1990s, where he had done business with a number of high-ranking former Soviet intelligence officers. He eventually came back to New York but had stayed in touch with some of them—potentially a major asset in signing a lucrative deal. He even boasted to Cohen that Trump Tower Moscow could somehow help the candidate win the election. "Our boy can become president of the USA and we can engineer it," Sater wrote in a November 2015 email. "I will get all of [Russian President Vladimir] Putin's team to buy in on this."

It didn't turn out as planned. The Moscow deal never came through and eventually led to tension between Sater and Cohen—tension that hasn't gone away. But to the shock of almost everyone, at least part of Sater's boastful email turned into reality: Trump's victory. Yet almost immediately, allegations of collusion with Moscow dogged his presidency. Russia had interfered in the election, with an intricate campaign of hacking, "fake news" and other forms of information warfare. And as U.S. investigators try to piece together what happened—and determine whether the Trump campaign coordinated its efforts with the Kremlin—Sater's boastful emails have piqued their curiosity.

Cohen, now the subject of a federal investigation, has been summoned to talk to special counsel Robert Mueller, as well as the House and Senate intelligence committees. They were interested in Sater too. Suddenly, reporters began hounding him, showing up at his house on Long Island, calling him at all hours. The negative publicity hurt his career in real estate, and his wife of more than two decades, with whom he has three children, has left him. As for the president of the United States, he claims he wouldn't recognize Sater—a man he had a business relationship with for years—if they sat in a room together.

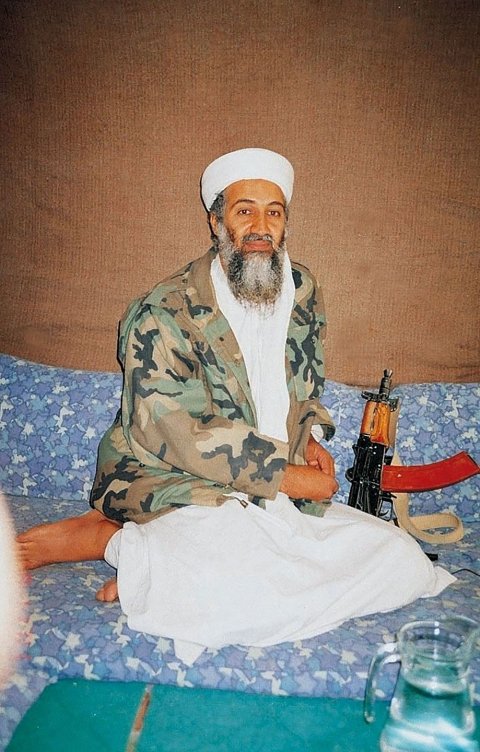

In the two years since the Trump-Russia scandal exploded into the headlines, few have been the subject of more curiosity and speculation than Sater. There were endless press reports about his background: He was an ex-con, purportedly with links to the Mafia, who had worked with Trump on failed real estate deals in Florida and Manhattan. Rumors surfaced that his former real estate company, Bayrock, was a money laundering vehicle for corrupt business and political figures in Russia and Ukraine (something he denies). He also picked a peculiar moment—the middle of Trump's presidential campaign—to try to revive the Moscow deal, bragging about his clout with Putin, one of Washington's most potent adversaries. And the only public defense—hinted at in court documents over the years—seemed to be an improbable story about how he'd wound up helping America track down Osama bin Laden, among other adventures in espionage.

So who is Felix Sater? Is he connected to the mob? Is he a spy? Trump's man in Moscow? Or is he a key figure in Mueller's investigation, the man who will ultimately bring down the president and finally answer the questions swirling around Russiagate? Pundits have speculated about all of the above. But over three meetings and more than eight hours of conversation, Sater offered new details about his life—from rumors about his Mafia connections to his encounter with Russian hackers in St. Petersburg.

And his story—the way he tells it, at least—is stranger than I had ever imagined.

An American Tale

"I'm tired of reading this shit," Sater says.

It's early May, and we're sitting at a coffee shop inside the Mandarin Oriental, a tony hotel in Washington, D.C. Sater had traveled there to testify before the House Intelligence Committee. The 52-year-old, wearing a blue blazer with an American flag pin affixed to the lapel, explains how much of what's been written about him is false. It's why he's been spending a lot of time with journalists. His campaign for "personal redemption," as he calls it, began earlier this year with a lengthy article on BuzzFeed, followed by a couple of TV interviews and now our coffee talk. And he wants his reputation back.

The most interesting thing about Sater is what that reputation consists of. In 1972, his family emigrated from Moscow. They were among the first wave of Jews allowed to leave the Soviet Union during the Cold War. For a year, they lived in Israel before moving to Coney Island, a neighborhood in Brooklyn where many Russian immigrants wound up. Sater was 6 years old when he arrived in the states.

Sater grew up as a normal Brooklyn kid. His father worked as a cab driver, and young Felix attended public schools. He also performed odd jobs and hawked The Jewish Daily Forward, a newspaper, in Brighton Beach.

After high school, he enrolled at Pace University, but his college days didn't last long. He got a part-time job on Wall Street at a boutique investment bank and loved everything about it. "I breathed it in like it was air," he says, becoming a full-time broker by the age of 19—a symbol of success in his old neighborhood. Within a few years, Sater was making serious money. He married his wife, and the two moved into a fashionable Upper East Side apartment building, developed by Fred Wilpon, the owner of the New York Mets. One of their neighbors was the team's star first baseman Keith Hernandez. "I was living a fairy tale life," he says.

But one night in 1991, he went out drinking with some of his colleagues, and a combination of "alcohol and testosterone" resulted in a bar fight. The way he tells it, a currency trader came at him with a beer bottle, so he grabbed a margarita glass, broke it and stabbed the guy with its stem. It took 115 stitches to sew up the man. Sater landed behind bars in New York's infamous jail Rikers Island.

Released after a couple of months—a judge allowed him out on bond while he was appealing his conviction—he was unable to get a legitimate job on Wall Street; the case had sullied his reputation. So Sater joined a firm that was running an old-fashioned pump-and-dump operation straight out of The Wolf of Wall Street: It bought thinly traded stocks and then talked them up to hapless customers, scamming them out of tens of millions of dollars. A few months later, Sater's appeal failed, and he ended up back at Rikers, where he served more than a year behind bars for the assault in the bar.

It was the worst period of his life. "[I] had a wife and a young daughter to take care of," he says. "I didn't know what I was going to do when I got out. It was bleak."

A Spy Among Friends

Once out of jail, Sater went back to his job at the pump-and-dump operation; because of his rap sheet, he still couldn't find work in legitimate finance. But after about six more months, he says, he quit. "I was disgusted with myself," he says. "I needed to leave the dark side."

His next stop: Russia. By the time Sater arrived in the mid-'90s, the Soviet Union had collapsed, Boris Yeltsin was in power, and Moscow had embraced a lawless version of capitalism. The city was anarchic, ruthless, but full of opportunity. Through connections on Wall Street, Sater started a telecommunications company in Russia selling transatlantic cable for voice and data transmission from the newly democratic countries of the former Soviet Union to AT&T. During that era, the once-powerful Soviet military and intelligence services were in disarray. Large swaths of both were being privatized. A bevy of former military officers and intelligence operatives went to work for businessmen—some legitimate, some with ties to organized crime, all looking for a piece of the new Russian economy. One man, a senior Soviet military intelligence official in Afghanistan during the Red Army's occupation, took an interest in Sater and his telecom company.

Sater won't divulge the man's real name—he just refers to him as "E"—but he was an acquaintance who changed the American's life in unimaginable ways. The two soon became close, and Sater routinely went to banyas (saunas) with E and his friends to drink and relax. Almost all of E's friends were also former high-ranking military or intelligence officials.

One night, the group went out to dinner, and Sater met an American named Milton Blane, who introduced himself as a consultant. A few days later, Blane invited him to a popular British pub in central Moscow. He told Sater he was connected to "some serious people,'' guys who had extraordinary access to senior levels of the Russian armed forces. OK, Sater said, so what?

Blane was an officer of the Defense Intelligence Agency, operating out of the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. Sater, with his ties to "E" and his friends, could be very helpful. To Sater's astonishment, Blane was recruiting him to become an intelligence asset. The U.S. was working on anti-missile defense systems, and the DIA wanted to find out how Moscow's worked. (Former FBI and CIA officials support Sater's account. Like many government officials interviewed for this story, they asked for anonymity because they weren't authorized to speak about the matter.)

Sater says it took him "about three seconds" to decide. "I'm in," he told Blane, a decision he now says was driven by both "patriotism" and a "romantic notion" of espionage.

He had no idea what he was getting himself into.

Mobsters, Feds and Jihadis

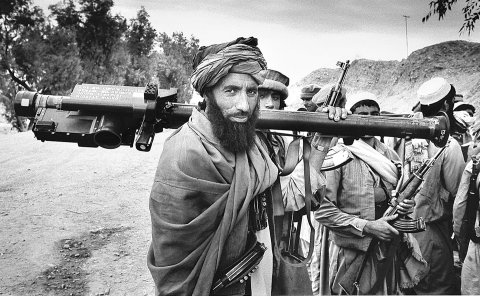

Because of E's time in Afghanistan, he was familiar with the country. One of his closest contacts was a senior intelligence officer for the Northern Alliance, a group at war with the Taliban for control of the country in the wake of the Soviet withdrawal. Moscow was the Alliance's chief source of arms, and this contact—I'll call him "Hamid"—frequently traveled back and forth to Russia.

During the Soviet occupation, the U.S. had supplied stinger missiles to rebel groups fighting the Red Army. Once the USSR pulled out, however, American policy eventually changed; it became clear that jihadi groups, including Al-Qaeda, might use the missiles for terrorism. In 1995, President Bill Clinton signed an executive order to round up as many of the stingers as possible in Afghanistan.

Both Hamid and E knew what Sater was doing, who he was working for. And for the right price, they offered to help the Americans reacquire some of the missiles. Sater relayed this message to Blane, who asked for proof. The Afghan sent photos of the serial numbers of the stingers, paired with the same day's newspaper. Impressed, Blane turned the matter over to the CIA—which was tasked with collection—and the agency began negotiating to buy back the missiles. Sater then began dealing with Langley. (He believes his information helped the agency recover at least some of the missiles, but he can't say for sure.)

Late in 1998, Sater got a call from an FBI agent in New York named Leo Taddeo, who told him about an investigation into the pump-and-dump operation on Wall Street that Sater had left behind—part of a broader probe into the Italian Mafia's expanding presence on Wall Street. The FBI had some dirt on Sater, who had gotten involved with two Brooklyn mob members—"guys whose job it was to keep other mobsters away"—before he went to Moscow, and Taddeo told him he was likely to be charged with fraud. If he came back and cooperated, a judge would take that into account at sentencing. (A former FBI official in New York says Sater's story is accurate.)

Sater agreed to return to the states. He then called E and told him what was going on, and the former intelligence official asked him to delay the trip, not saying why. Two days later, E provided Sater with a packet of information from his Afghan contact, Hamid. It included numbers for the satellite phones used by a man then living near the Afghan border with Pakistan: Osama bin Laden, the leader of Al-Qaeda, the jihadi group that had just bombed the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. (A former CIA officer familiar with Sater's story says the agency came to believe the numbers were authentic.)

When Sater arrived back in the U.S. in late 1998, he met with Jonathan Sack, the assistant U.S. attorney in New York's Eastern District, who was handling the stock fraud case. Sater told him what he had been doing in Moscow, and the CIA and DIA backed up his claims. Both agencies wanted their asset sent back to Moscow, but Sack was unmoved. And Sater was mystified. "So I'm giving the CIA bin Laden's sat phone numbers," he tells me, "and this guy [Sack] is more concerned with going after 'Vinny Boom Botz.'"

Sater pleaded guilty to fraud and agreed to help the feds with the stock case. "I did 10 or 15 debriefings," he says. "They ended up satisfied." Sack agreed to delay his sentencing.

Clinton that summer had ordered an airstrike on Al-Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan, based in part, former CIA sources say, on information Hamid had passed on. "[The CIA] really wanted me to go back [to Moscow] at this point," Sater says. But Sack and the FBI still wouldn't allow it.

In late 2000, as Sater helped the feds take on the mob, he also tried to make some money. He joined a real estate business—Bayrock—and the company managed to get a few deals, he says.

His work as a government informant was equally fruitful. Two FBI sources say Sater's cooperation would eventually help turn Frank Coppa, a captain in the Bonanno crime family, into a cooperating witness against the mob organization—"a real turning point in the war on the Mafia," a source says. Eventually, his cooperation on the stock scams helped the feds get 19 guilty pleas, according to Sater and law enforcement officials.

That figure seemed significant at the time, and Sater says he "hopes" it helped atone for his crimes. But the Mafia cases would turn into an afterthought compared with his next role—one that was even more improbable.

Greed Is Good

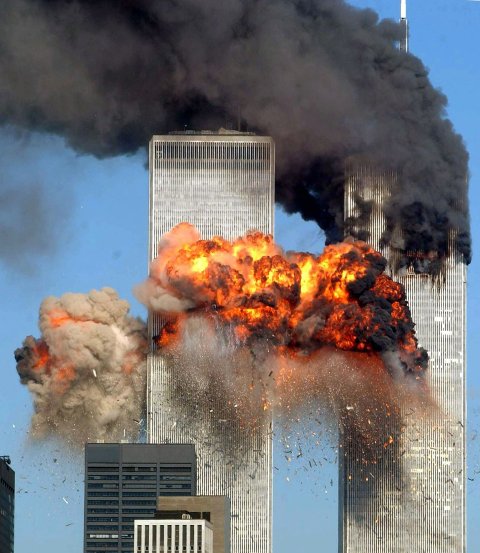

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Sater was still working at Bayrock and making his normal morning commute into Manhattan. But when he neared the Midtown Tunnel, he saw it: The twin towers of the World Trade Center had been hit by planes, one after the other.

Sater doesn't remember exactly when he realized bin Laden was responsible for the carnage. But once he did, he says, his mind raced back to his time in Moscow, when he was funneling information to the U.S. government. One bizarre episode stood out, he claims: In the spring of 1998, he, E and about 15 or 20 ex–Soviet special forces fighters went to Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, a former Soviet republic that borders Afghanistan. They had information from Hamid's sources in the Northern Alliance about bin Laden's location—a camp in the mountain range called Tora Bora. Hamid had proved his bona fides, so "we had no reason to doubt what he was telling us," Sater claims. And E and his men were going to try to take out bin Laden—for a price. They drove from Dushanbe across the border to Mazar-i-Sharif, where they rendezvoused with Northern Alliance fighters.

Sater claims he called Langley, saying he had real intelligence about bin Laden's whereabouts and soldiers who were willing to move on the camp. What he needed to know was how much the agency would pay. "Greed was always my go-to weapon," Sater says. Getting E into potentially lucrative telecom deals, as well as Sater's background as a Russian-speaking former Wall Street guy, had cemented his relationship with the former military intelligence officer.

The CIA, Sater says, told him the bounty on bin Laden was $5 million. He claims he told the agency that wasn't going to cut it: "These guys were walking into a potential bloodbath. There were about 50 of [them] total. They needed at least a million dollars each." The CIA balked, Sater claims, and the group retreated to Dushanbe, then back to Moscow. (Three former CIA officials declined to either confirm or deny this account. Hamid couldn't be reached for comment.)

As bin Laden's face became a permanent fixture in the papers and on the news, Sater couldn't shake the thought out of his mind: "Could we have had him? Was that a possibility? I'll never know."

Not long after the 9/11 attacks, the FBI again reached out to Sater. Only this time the bureau wanted him to get in touch with Hamid—and help with counterterrorism—not the mob. The American informant did what the bureau asked, and he knew what to expect from the Afghan. "What's in it for me?" Hamid asked. He "didn't give a damn about Americans,'' Sater says. But Al-Qaeda had recently assassinated Ahmad Shah Massoud, the leader of the Northern Alliance, so the Afghan said he would help if the money was right.

Sater had already given this some thought. He claims he told Hamid—accurately, as it turned out, but not because he knew anything—that the Americans would soon invade the country. The Afghan needed more than that. So Sater claims he assured him the U.S. would depose the Taliban and set up a central bank in Kabul. The Afghan, he says, could help run it. This was a complete lie, but Sater says he sold it by putting together a packet of official-looking legal documents, allegedly from the U.S. government, authorizing the creation of the bank. He shipped them and a satellite phone to Hamid, who believed the story, according to Sater.

Soon, the American asset says, before the first CIA paramilitary operators entered Afghanistan, the information started to flow. It was detailed and specific, and even included locations of Al-Qaeda fighters, weapons cachess and information about how the 9/11 attackers had financed their operation. The way Sater recalls it, a relative of his Afghan informant was married to Taliban leader Mullah Omar's personal secretary, and they traveled everywhere together, including to the caves of Tora Bora, where he and bin Laden retreated after the United States invaded.

For Sater, the work was surreal and often gratifying. "FBI agents would come to my house each night and stay there until 2 or 3 in the morning," he says, "drinking my wife's coffee, poring over this stuff." (An FBI official who knew Sater at the time said the general outline of this story is accurate but declined to go into specifics.) Sater says he has never been paid by any U.S. government agency for his assistance, and current and former FBI officials confirm that. "As all this was going on," Sater says, "I just remember thinking how crazy it all was. "How in the fuck did I get involved in all this?"

Hackers, Liars and Journalists

In the early 2000s, not long after the war in Afghanistan began, Sater says he met Trump, thanks to his work for Bayrock, the real estate company. (Neither the White House nor Cohen would comment for this story.) Sater raised money for Bayrock from, among others, a wealthy businessman from the former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan, and he persuaded people in Trump's orbit—including Cohen, his old friend—to bring his deals before the boss.

Two of the ideas worked out. Sater and the New York real estate mogul eventually worked on the Trump SoHo in Manhattan and a hotel and condo project in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, which failed after the 2008 economic crisis. He and Trump, Sater claims, were friendly but not particularly close. As Abe Wallach, a former Trump Organization executive, once told the journalist Tim O'Brien, "It's not very hard to get connected to Donald if you make it known that you have a lot of money and you want to do deals and you want to put his name on it."

But Trump eventually distanced himself from Sater, after The New York Times published an article detailing the latter's criminal conviction for assault, as well as his role in the stock scam case. "If he were sitting in the room right now, I really wouldn't know what he looked like," Trump said of Sater in a 2013 video deposition taken in connection with a civil lawsuit. Two years later, as Trump was running for president, a reporter asked the Apprentice star about his former business partner, and he replied: "I'm not that familiar with him." For Sater, these comments were hurtful, but he didn't stop trying to work with Trump; there was still money to be made.

Nor did he cease working with the FBI. Law enforcement officials say that beginning in 2005—and continuing for several years afterward—Sater helped break up a Russian ring in St. Petersburg that was hacking into the U.S. financial system. Taddeo, the FBI agent who had summoned Sater back to the U.S. in the pump-and-dump case, worked with him on the case. The two men traveled to Limassol, Cyprus, a popular post-Soviet vacation spot for Russians. Under the FBI's watch, Sater had infiltrated the hackers, helping them launder money, and even met with the group's ringleader in Cyprus.

The irony of this operation is not lost on Sater. According to an indictment brought by Mueller, it was allegedly a St. Petersburg outfit, the Internet Research Agency, that spread "fake news" in the U.S. before the 2016 election. I asked Sater whether the FBI has indicated that the cases he worked on were linked to the same group, or to the alleged Democratic National Committee hackers. "It could be part of the same group," Sater claims. "They've told my lawyer that some of the information we gathered is still 'actionable.'" (The Department of Justice declined to comment on the matter.)

Either way, in court proceedings and in testimony before Congress, various law enforcement officials have consistently vouched for Sater—including former Attorney General Loretta Lynch, who told the Senate Intelligence Committee that he had provided "valuable and sensitive" information to the government when she was running the U.S. attorney's office in Brooklyn. Which is why when Sater was finally sentenced for the stock scam case in 2010—a case brought against him 12 years earlier—he got just a $25,000 fine.

For a once-convicted felon who had taken part in a multimillion-dollar scam, that was nothing.

'A Bit of a Blowhard'

Hackers. Terrorists. Spies. Mafioso. The future president of the United States. Unbelievably, for a kid from Brooklyn, all of these people have been in Sater's orbit. And now he's splitting his time between New York and L.A. and trying to become a Hollywood producer. He's like Zelig, I tell him as we finish our breakfast during our final meeting, at the Mandarin Oriental in D.C. He chuckles at the reference, the main character from a 1983 Woody Allen movie who becomes a bit player in the lives of historical figures, from Adolf Hitler to Al Capone.

But as the Russiagate probe continues, Sater's Zelig-like role in the affair remains murky. It's hard to know what to make of his story, hard to pin down where Sater the dealmaker begins and Sater the asset ends. Mueller's investigators—some of whom Sater has worked with during his years as an informant—are said to be interested in the Trump Tower Moscow project. (E, the ex-Soviet intelligence officer, was reportedly part of it as well.) They're apparently interested in a Ukrainian peace deal Sater and Cohen tried to broker—one that would have involved lifting U.S. sanctions on Russia—a result the Kremlin has long desired. And the special counsel is also interested in money laundered from Russia and Ukraine, which could bring into focus how an obscure—and now defunct—investment bank in Iceland, the FL Group, was able to invest $50 million in the Trump SoHo project. Some suspect the company was laundering money out of Russia. Jody Kriss, a former colleague of Sater's, made this accusation as part of a civil lawsuit against Bayrock alleging racketeering and claimed Sater used to brag about how close the bank was to Putin. Sater denies that, and the two settled the suit earlier this year. The Moscow-born dealmaker claims he answered all of Mueller's questions to the special counsel's "satisfaction," adding that investigators told him he is not a target in the probe. (The special counsel's office declined to comment.)

Today, Sater seems weary of the Russiagate queries—and the questions it has raised about his background. Some have alleged he has ties to Russian organized crime, which Sater calls "bullshit." There are rumors that his father was a capo in a gang run by alleged über boss Semion Mogilevich; Sater denies that as well. His father, he acknowledges, ended up in the "dispute settlement" business in Brooklyn after he could no longer drive a taxi because of a back injury. He pleaded guilty in 2000 to extorting restaurants and other small businesses in Brooklyn and got three years' probation. But he was not working for the so-called "brainy don," as Mogilevich is known. "My father wouldn't know Semion Mogilevich if he fell on him," Sater says. Besides, he adds, "I helped the Justice Department prepare a stock fraud case against [Mogilevich]" in 2011. (Two FBI sources back up Sater's claims. Mogilevich did not respond to questions for comment through his lawyer in time for publication.)

Over the past year, some press reports have speculated that Sater was a source for the Steele dossier, the explosive memos written by a former British spy alleging that the Kremlin coordinated parts of its interference campaign with members of the Trump team. "Not true," Sater says. "I swear on the heads of my children."

Others have also suggested he might turn on Cohen; as BuzzFeed first reported, the two occasionally bickered over control of the Trump Tower Moscow project, among other things. After receiving a referral by Mueller, the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York is now investigating Cohen for possible bank fraud. Would Sater serve as a witness against him? "Against him?" Sater says. "I doubt it," adding that he has no information about the case.

It may look strange—suspicious even—that he and Cohen were pursuing a major real estate deal in Moscow. In the middle of a presidential campaign. On behalf of the Trump organization. With a foreign power, an adversary that was—at the exact same time—interfering in the U.S. election. But on November 8, 2016, Sater claims that he, like many others, watched in "disbelief" as Trump was elected president. "No one thought he would win. And that includes Donald."

Even though he supported him, Sater allows that "Donald is a bit of a blowhard." And perhaps, he suggests, he too has dabbled in puffery, which is how he explains his statements about Trump Tower Moscow—that he could push the deal through, that a real estate venture could somehow determine the outcome of an American election. Years ago, Sater apparently had enough clout to get Ivanka Trump into Putin's then-empty Kremlin office, where she twirled around in his seat. But now he suggests that he and E are not so connected that they could easily get Putin's personal approval on a high-profile real estate deal with Trump's name on it.

As we stand in the lobby at the Mandarin Oriental, I have one last question for Sater: Does Mueller really have anything on the president? The enigmatic informant-cum-dealmaker offers what seems to be a sincere response. "I think," he says, "Donald is going to be re-elected."

He smiles broadly and adds something he's told other reporters before: "And after his second term, then we'll do Trump Tower Moscow."