Peter Weir keeps his webcam covered with tape these days. He doesn't want anybody watching him.

Can you blame him? Weir, after all, directed The Truman Show, the incisive satire-drama from 1998 that seems startlingly prescient today. Back then, the movie drew acclaim for its imaginative storyline and barbed commentary. Two decades later, it resembles a veiled warning, both as an astute predictor of reality television's enormous rise and as a cultural forerunner to the age of digital surveillance. So profoundly has the film invaded the pop cultural psyche that there is now a psychiatric delusion named after it.

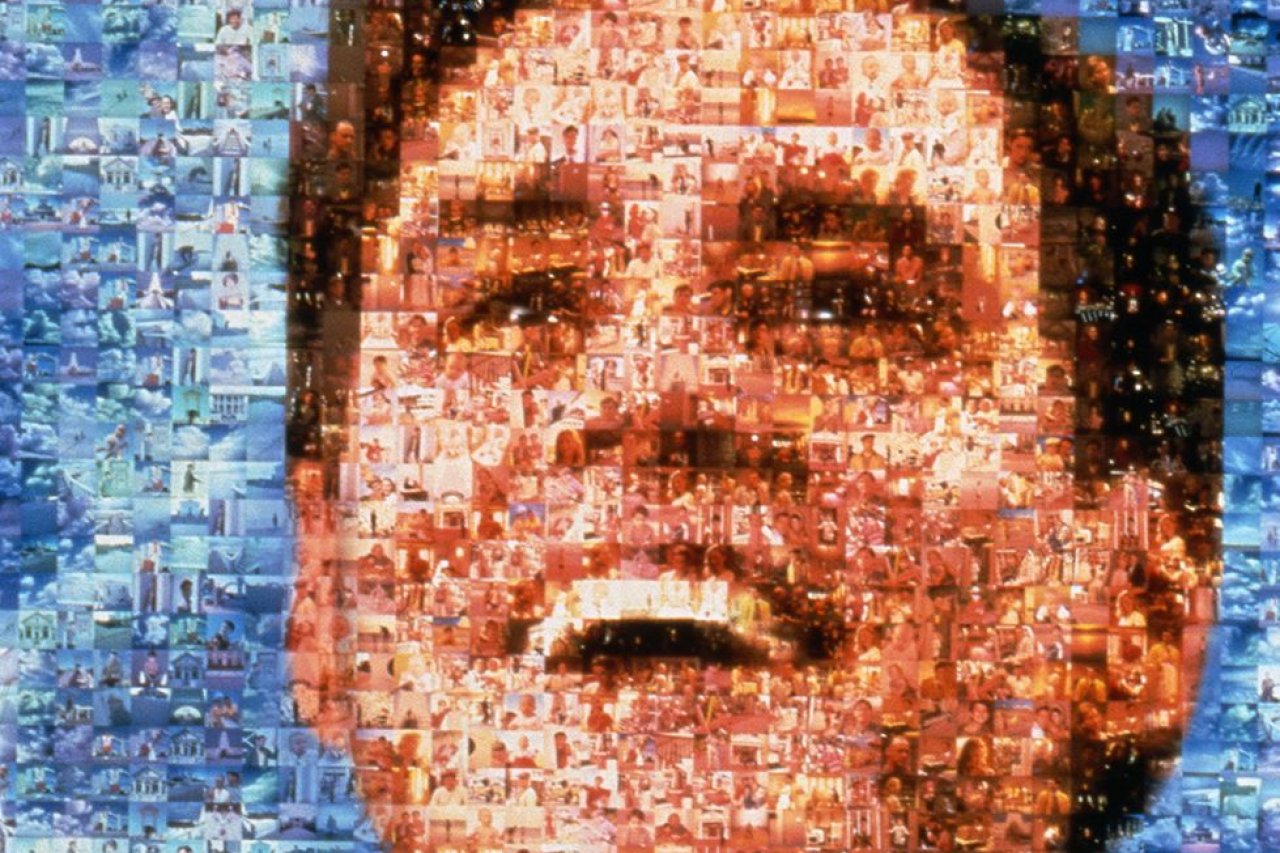

The film stars Jim Carrey as the happy-go-lucky insurance salesman Truman Burbank, a man whose every moment, unbeknownst to him, has been broadcast on television, turning his life into a 24-hour reality show. Millions have watched him grow up, go to school, fall in love, get married, eat, sleep, brush his teeth. Things get interesting when he begins to suspect he is the involuntary star of America's favorite TV series.

Twenty years ago, Truman's life of constant surveillance seemed like a flight of paranoia. After reading the original screenplay by Andrew Niccol, Weir thought "it was just wonderful speculative fiction," the director tells Newsweek. "My main concern was the credibility of it. There wasn't enough precedent." Some friends told him the plot stretched the limits of believability: "No one would watch a thing like that," they said. "Who wants to watch reality?"

Answer: a lot of people. Reality TV wasn't entirely new in 1998. The first such show, Candid Camera, came on in 1948, and MTV's Real World began in 1992. But it wasn't until the American Survivor debuted in 2000 that the genre became a mainstream obsession (the season finale drew more than 50 million viewers). For the next decade, reality TV would dominate prime-time television, giving one star, Donald Trump, a springboard to the White House.

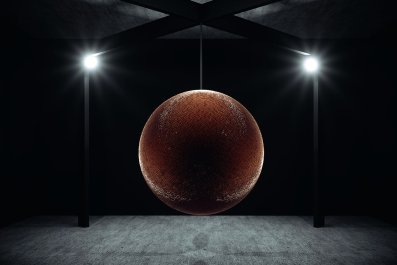

Weir's film, which was a critical and financial success, contains a fascinating duality between utopian and dystopian elements. On the one hand, Truman's home of Seahaven Island—actually a television set constructed within a massive dome—is an idyllic, postcard-perfect place to live. (As Christof, the show's God-like creator, tells Truman when he realizes his life is a simulation: "In my world, you have nothing to fear.") But this paradise is also outfitted with 5,000 hidden cameras and funded by product placement. We learn, as the plot unfolds, that Truman is the first human being to have been "legally adopted by a corporation." As Sylvia (Natascha McElhone), the show's most outspoken opponent, observes, "He's not a performer, he's a prisoner."

The first draft was completed in 1991, and predated MTV's Real World by a year. Back then "there were no reality shows," says Niccol in an email. "I would argue that there still aren't. When you know there's a camera, there is no reality."

Niccol's original treatment dialed up the nightmarish elements of this world. "The Truman character was sadder and kind of strange," says Weir. In this early version of the film, set in New York, Truman had a drinking problem and visited a prostitute. The Australian director (whose previous hits included Picnic at Hanging Rock and Dead Poets Society) thought people wouldn't watch the fictional show within the movie: "It was too depressing and oppressive, 24/7," he says. Weir signed on to direct the film about a year after producer Scott Rudin purchased the script in 1993, on the condition that he could rework the script with Niccol. They eventually settled on a sunny, resort-like setting, where the unsuspecting star would be "a kind of back-slapping, grinning friend to everyone."

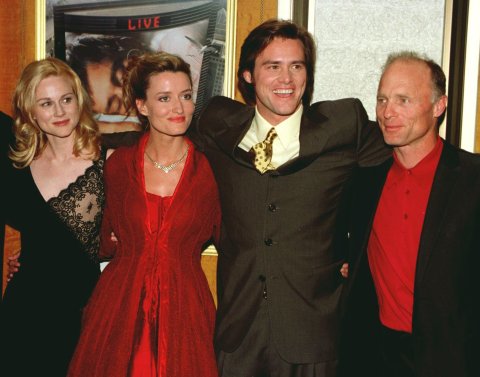

Weir wanted Carrey, with his rubber-faced comedic zeal, and he was willing to wait a year for the actor, then busy with The Cable Guy and Liar Liar, to become available. "I thought of Tom Hanks, but he had already done Forrest Gump and it was too close," he says. Ultimately, "there was no one else I thought could pull it off. And there was no question that this had to hit the target dead center." Otherwise, the film "would collapse."

Carrey had recently become a huge star, and he identified with Truman's sense of being constantly watched. "I can draw off the feelings I have," Carrey reportedly told the director. "I'm a prisoner." It would become the actor's first foray into drama, setting him up for later roles in Man on the Moon and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Carrey and Weir initially clashed. "After a take, Jim would come out and say, 'Let me have a look at that,'" the director recalls. "I was stunned. I said, 'You don't need to look. I'll tell you if it's working or not—that's directing.' He said, 'No, no, I need to evaluate my performance.'" Weir began allowing Carrey to view the takes he printed, then realized this was interfering with the character's unwitting innocence: "I said to him, 'Jim, it's harming your performance. Truman doesn't know he's on television. So you shouldn't be looking at yourself.' He trusted me."

Truman, a sort of glorified lab rat, is manipulated by producers who stage dramatic plot twists, like the feigned death of Truman's father. His family and friends and co-workers, he comes to discover, are all actors taking direction. "Was nothing real?" he asks Christof during the film's emotional climax. (A rare moment in cinema: A human character confronts his omniscient creator.) "You were real," Christof says. "That's what made you so good to watch."

Christof grasped the business model that would drive the success of YouTube and social media: base voyeurism. The crucial difference, of course, is that these real-life stars know they're being filmed. Or maybe they're doing the broadcasting themselves, as in the case of absurdly popular YouTubers like Logan Paul.

The Truman Show's emphasis on product placement (Truman's friends and family incessantly shill brand-name items when talking to him) seems particularly prescient now. Instagram celebs make substantial cash from sponsored content, and the intrusion of corporate brands into our private lives has become a commonplace phenomenon. It's now commonplace to willingly hand over the digital detritus of our private lives to real-life technology companies as powerful as the one that adopted Truman.

"There's nothing more chilling," Weir says, "than the little thing that happens quite regularly: You're looking something up on the internet one day—you're thinking of a holiday somewhere in eastern Europe—and up comes information about towns in Eastern Europe the next day."

The most curious legacy of the film has been observed not by critics but by psychiatrists. While working at Bellevue Hospital Center, Dr. Joel Gold noticed the phenomenon of delusional individuals believing their lives were reality shows being staged for others' entertainment. Later, he and his brother, Ian Gold, a neurophilosopher, dubbed this form of psychosis the Truman Show Delusion, describing its characteristics in a 2012 paper and a 2014 book, Suspicious Minds: How Culture Shapes Madness.

Indeed, the sense that one's own reality is simulated or staged certainly predates the film. Weir says that during the casting process in 1996, "I came across at least three people who said when they were young, they had a feeling their life was a show." But the more extreme version of paranoia is a common symptom of psychosis, and Gold found that The Truman Show resonated particularly with some of those patients. Several mentioned the film by name. "They said, 'Did you see The Truman Show? That's my life.'"

One patient, in late 2001, became convinced that the 9/11 attacks had been staged for the benefit of his reality show, and he traveled to New York City in order to see whether the World Trade Center was still intact. Another had worked in reality television on the technical side before becoming convinced his life was reality television.

In 2013, the New Yorker profiled a man suffering from the delusion who attended a Dave Matthews Band concert, believing it was meant to be his show's climax, a grand finale where his father would present him with a check for a million dollars. "Often people will believe that when their show ends, they'll be rewarded," Gold explains. "There will be this big reveal, and all their friends and family—their true friends and family—will be waiting for them."

By the time The Truman Show turned 15, in 2013, the rise of both social media and government surveillance had made its central anxiety seem reasonable. "Putting this illness aside, the notion that we're all watching one another has come to fruition," says Gold, who has left Bellevue for a private practice but is still contacted every month (if not week) by new patients describing the delusion.

According to one oft-repeated story, Weir wanted to play with these sorts of anxieties during the film's theatrical run: The idea was to have a video camera installed in every theater, then have the projectionist abruptly switch from the movie to a shot of the viewers themselves. Was this really under consideration? "It was probably a joke," Weir says now. "I think what's been lost is the 'Ha ha ha' that followed that thought. That would show that I was turning into Christof."

Both he and Niccol are amzed by the film's endurance. As Niccol puts it: "I guess I'm most surprised that while Truman was running from cameras, most of society is running towards them."