In 1970, Robert Longo was a senior at Plainview High School on New York's Long Island—a football star with long hair who smoked pot. "I wasn't good in school, and I was worried about getting drafted and going to Vietnam," he says. "I'd seen guys older than me come back totally scrambled."

On May 4 of that year, the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four students during an anti-war demonstration at Kent State University. One of them, Jeffrey Miller, had graduated from Plainview a few years earlier. In John Filo's now iconic Pulitzer Prize–winning photo, Miller is the 20-year-old man lying face down on the pavement as a young woman crouches over him—the two forever a symbol of the country's social unrest.

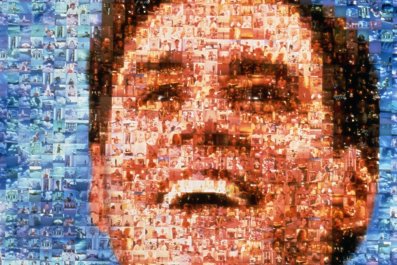

Longo would go on to become one of America's most important contemporary artists, a member of the groundbreaking Pictures Generation (1974 to 1984); along with Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince and Barbara Kruger (among others), Longo rejected minimalism and conceptualism, often using appropriated images inspired by newspapers, advertisements, film and television. But Filo's photo of Miller, a catalyst for the artist's social activism, "is one of those images I could never make art out of," he says. "It still haunts me."

The work that got him noticed, Men in the City, is a series of 35 photorealist charcoal-and-graphite portraits, of businessmen and women in suspended animation, flailing and falling. Though not overtly political, each anonymous portrait is a potent skewering of '80s excess and alienation. "I came up as an artist under Ronald Reagan—the pre-Trump Trump," says Longo. "He was the guy who said 'Make America Great' first. I remember him talking about returning the country to traditional values, and I thought, What does he mean—owning slaves?"

In the years since, controversy and tragedy—war, immigration, police brutality and government corruption—has continued to preoccupy him. His latest work, Death Star, tackles one of the most contentious issues in America: gun violence. It's far more complicated, the artist notes, than the crises of his youth. "In 1968, it was obvious that the Vietnam War and racism were wrong," he says. "Today, the magnitude of our problems is far more complex. Stricter gun laws, for example, will certainly help, but that's not going to solve the problem entirely. It's not clear exactly how to proceed."

"Death Star," debuting at Art Basel in Switzerland on June 14, is a massive ball composed of 40,000 bullets, a number that approximates the overwhelming number of U.S. citizens killed by guns over a year (not including suicides). The work is an update, of sorts, of a project—also called Death Star—that Longo completed in 1993 and composed of 18,000 .38-caliber bullets. The look of it was inspired by, "dare I say it, Star Wars and a disco ball," he says, though there was nothing whimsical about the incident that sparked the idea.

In 1993, Longo's son,14 at the time, came home to say that one of the kids at the local basketball court in New York City had pulled a gun. "My kid was really excited about it," says the artist, who has raised three sons with his wife, the German actress Barbara Sukowa. The "excitement" was a reaction to a change in the power dynamic. "You didn't have to be the strongest or the toughest kid anymore, you just needed to have a gun. It made me realize that I should pay more attention to guns," says Longo, who began to do research with the FBI, which led to the first Death Star.

The gun problem, you may have noticed, has exploded since then. "All my rage and helplessness has really amplified my work in the last three or four years," Longo says. "All these mass shootings!" It is not his choice, he adds, to make political art: "Making art in itself is a political act—the freedom of expression. I don't want to instruct or preach," he adds, "I want to present something that has a visual impact, that lets the viewer make a decision."

The biggest difference between the new Death Star and the original (now at the Burchfield Penney Art Center in Buffalo, New York) is the types of bullets used, a reflection of the nation's shift in preference, from handguns to AK-47s and Bushmasters. "What really killed me," the artist says, "is how much gunpowder these bullets contain—over twice as much as a .38-caliber. It's overwhelming."

Not that there's any gunpowder in the bullets. In 1993, he could purchase blanks in the mail, but that's now illegal in New York state. "So I had to buy the casings and tips separately, as well as a loader to put them together," he says. Yet after ordering tens of thousands of casings, "no one knocked on my door. Nothing. Sure, they don't have gunpowder in them, but it's not like that's hard to make!" The only question came after he had ordered an extra 4,000 bullets and the woman on the phone asked if he'd like to round off the amount of the purchase with a donation to the National Rifle Association. Longo laughs. "Are you fucking crazy?"

To compose the random sequencing of bullets—each attached by hand—the artist worked with a NASA engineer at Neoset Designs in Brooklyn, New York. Longo didn't want any recognizable patterns—because gun violence doesn't have one. The 2-ton result, which took over a year to complete, will be presented by Metro Pictures and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac at Unlimited, a curated platform for projects that transcend the classical art fair booths. (More of Longo's work will be at Art Basel, in the Metro Pictures booth.)

The bullet ball, as Longo calls it, will be hung at eye level, from a chain secured to I-beams. "I'm a big fan of the musician Nick Cave," he says, "and there's a line in one of his songs, 'Jubilee Street,' about a 10-ton catastrophe on a 60-pound chain. It reminds me of this piece."

Death Star will sit in darkness, with a high-intensity spotlight attached to the I-beam. As you walk toward it, the horizon of the edge starts to glow. "It's very trippy," Longo says, "because when you first see it you're not quite sure what it is. Once you get right up to it and you realize it's made of bullets, it becomes rather shocking. The amount of bullets is pretty insane."

It does seem, I suggest, that Death Star is intended as an anti-gun statement. Longo sighs deeply, then answers with an anecdote. "I was in college, taking acid and walking down the street with a friend," he says. "And I saw Jimi Hendrix's head in the tree ahead of me. I said to my friend, 'Do you see Jimi's head in the tree?' Of course he didn't see it, but later on I realized it was kind of like what making art is: You're trying to get people to see what you see."

A month or so before we spoke, on April 22, a white man, armed with a semiautomatic rifle, had killed four people at a Waffle House in Nashville, Tennessee. The incident reinforced the deep divisions and sad ironies that come with living in a highly racially diverse democracy: The man who saved the survivors, James Shaw Jr., was a young black man. "In a country where cops are afraid of black men with guns—and under different circumstances, might have arrested this guy—he was the one who grabbed a hot barrel with his hand and threw it away," says Longo.

Maybe, he suggests, the country is hardwired for violence. "America is insanely competitive," he says. "I'm insanely competitive." He points to his passion for football, a game that encourages and rewards brutality—something he was indoctrinated in at an early age. "I know football's bad, and I wouldn't let my kids play it," he says, "but I still love it."

The 2006 book Dangerous Nation, by the neoconservative Robert Kagan, got Longo thinking about America as a sports team. "It's a frightening concept, because what's the goal of a sports team? To win," he says. "To slaughter the opposing team, to humiliate them. So when 9/11 happened, there was no attempt to understand why it happened. They scored a goal, now we have to go and kill 100,000 of them."

That mentality—winning at all costs—whether you agree with it or not, is supported by millions of Americans. Longo believes that gun ownership is "ridiculous, and the NRA is horrendous. But there are people living in the woods who have to contend with grizzly bears. I have a friend in Montana who has tons of guns; I don't think he's going to kill anybody."

On top of that, he adds, is the undeniable economic incentive of manufacturers. "All the things I've bought lately are made in Pakistan or China," he says. "But most of the guns sold in the United States are made here. It's a huge industry. And the irony is that every time there's a mass shooting, the sales of guns go up because people are afraid of gun regulation."

It's odd to think that 40,000 bullets might be intended as a form of gentle persuasion, but for Longo it sort of is, particularly with both sides of the U.S. gun debate seemingly incapable of compromise or conversation. "The excessive sense of individuality that Americans have, which is exacerbated by the media, reinforces biases so that nobody trusts each other anymore," says Longo. The resulting and extreme tribalism, he notes, adds up to many different kinds of Americans. What art can do is "give you the chance to possibly fuck with biases, to say, Why don't you look at it this way or think about it a little differently?"

But isn't it likely that those attending Art Basel—arguably the world's most important art fair, attended by the richest collectors and dealers—will think much as he does? The European Union is definitely on Longo's side; its government has established stringent new gun controls. "You are preaching to the choir," he says, "but the thing about the choir is that they have to do something." For example, 20 percent of the sales of Death Star will go to Everytown for Gun Safety, a non-profit organization founded and largely financed by former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2014 as a way to match the National Rifle Association in political influence. "I'm not running out to protest or march," Longo says, "but there is a way that I can do something, and money is power."

Making beauty out of disaster can seem a contradictory pursuit, but Longo is following in a long tradition. He considers Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa to be "one of the greatest pieces of political art ever made. So is Picasso's Guernica," he adds. "And I watched something recently that was some of the best art I've seen—a music video by Childish Gambino [the alias of Donald Glover] called 'This Is America.'"

He talks about a moment in the video when Gambino, after shooting a fellow black man, hands off the gun to someone who wraps it, almost tenderly, in a soft red cloth before spiriting it away. Meanwhile, the body is roughly dragged off screen, suggesting that the instrument that ends a life is more valuable than the life it ends.

"It's fucking brilliant and moving," Longo says. "Kanye West must be dying when he sees it."