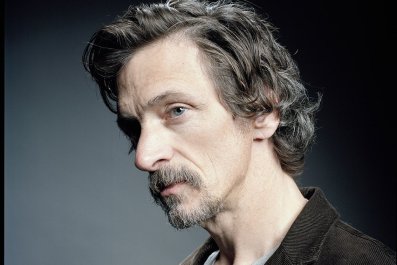

On January 11, 2016, Francis Whately overslept. An insomniac, Whately often struggles to fall asleep, though he's noticed that when something very bad happens, he tends to sleep right through it.

Whately's alarm didn't go off that morning. He woke around 9:30, turned on his cell phone and was greeted by two dozen text messages and voicemails: David Bowie was dead. There was a request to appear on a radio program, too, but Whately had already slept through it, which was fine, because he needed time to process this news. Two days after the rock star's 69th birthday, he had succumbed to a cancer he'd fought in secret for more than a year.

Whately, a documentary filmmaker and the director of the 2013 BBC film David Bowie: Five Years, which examines the star's 1970s and '80s heyday, was stunned. He had not known his hero was ill. And the timing was eerie: Bowie had just released his most daring album in decades, the freaky, jazz-addled LP Blackstar. Still, there had been clues, like the persistent imagery of death and mortality on the new album. "Look up here, I'm in heaven," Bowie sings at the start of one song. "I've got scars that can't be seen."

There was also the puzzling note Whately had received from Bowie a month before. "He wrote me a rather odd email saying that he was very happy with the new album," Whately recalls. "And he was very happy with his lot in life. And he said, 'What more can anyone ask for?'"

The filmmaker had noted the strangeness of the email, but figured that was just Bowie. "He would often write quite odd things," Whately says. "His emails were very amusing. And quirky. And unusual. It was only after he passed away that I thought, 'OK, is this actually him saying goodbye?'"

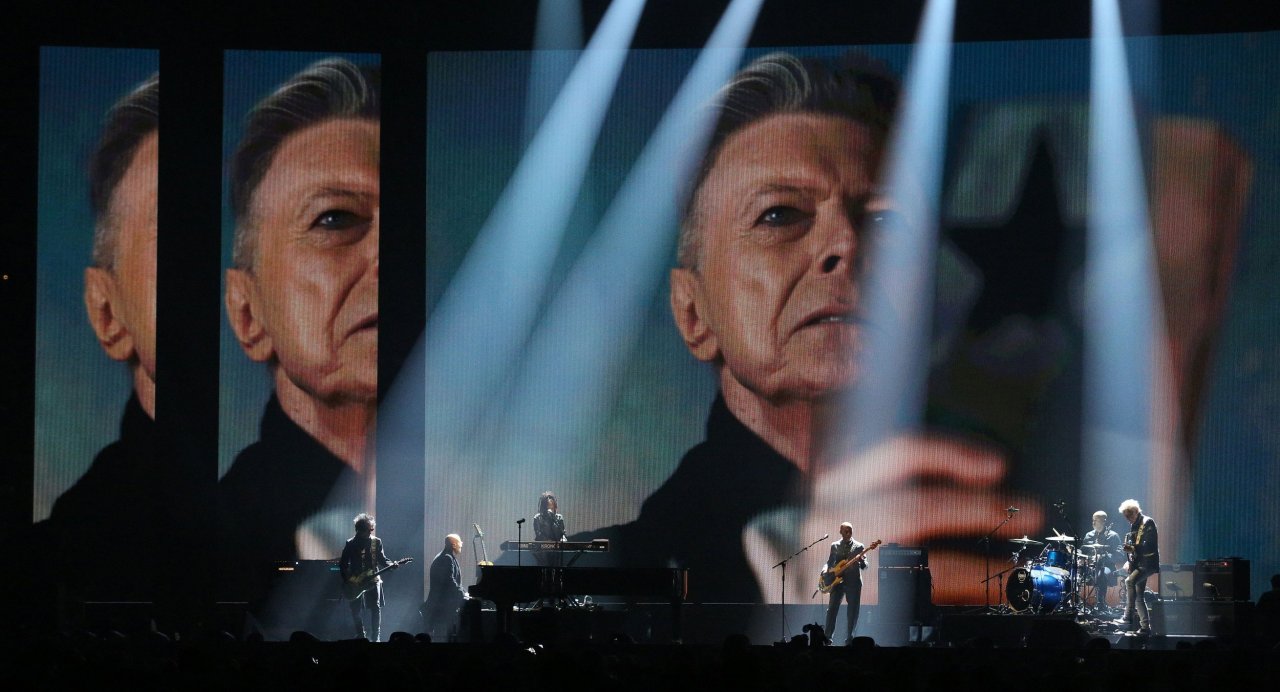

Indeed, it seems Bowie was saying goodbye—in email, in song, in secret. The pop star's death was so eerily timed to the release of his musical farewell that it seemed like mortality itself was part of the fabric of his art. Whately's new film, David Bowie: The Last Five Years, traces the contours of that musical farewell. The film (debuting on HBO on January 8—Bowie's birthday) examines the sudden shock of inspiration that overtook Bowie during the final years of his life, both before and after his 2014 diagnosis with liver cancer. Whately recreates the making of the star's last two albums, The Next Day (2013) and Blackstar (2016), and peers behind the scenes of his stage play, Lazarus, which opened off-Broadway in late 2015.

Despite its title (a nod to the Ziggy Stardust track "Five Years"), the film's story really begins years earlier, in 2004. That was when Bowie's final world tour came to an abrupt end, after the star suffered symptoms of a heart attack onstage in Germany. Bowie's bandmates recount the frightening moment he began sweating profusely and lost his ability to sing. After undergoing an emergency angioplasty, the star retired from touring and vanished into private life in New York City. Years passed. Bowie's 60th birthday came and went. Fans assumed the pop chameleon was done making records. Then, in 2011, members of his band got an email: Bowie was ready to work again.

Related: David Bowie, Leonard Cohen and the art of the farewell album

The Next Day—which would become Bowie's first studio album in a decade—was recorded in deep secret, as though it were a CIA operation. Musicians were required to sign NDAs. Bowie set up shop at The Magic Shop, a downtown Manhattan studio where interns were dismissed on the days he was recording, to limit the possibility of a leak. (He successfully kept the project quiet.)

Whately wanted the documentary to provide an intimate glimpse of those recording sessions. That proved tough. "[Whately] kept saying to me, 'Oh, we'll get the footage from the Next Day sessions,'" says guitarist Gerry Leonard, who has worked extensively with Bowie. "In the back of my mind, I was like, 'There was no footage.' I know there was no footage. David was so private about those sessions."

Faced with this obstacle, Whately chose an unorthodox approach: He rounded up the musicians who played on The Next Day and had them "recreate" the sessions. "I think it was a catharsis for them, to play this stuff again," he says. Onscreen, Leonard and his bandmates demonstrate how they performed material like the Motown groove in "The Stars (Are Out Tonight)" and describe how Bowie directed the songs to completion. "He was a giant to be in the room with," Leonard tells Newsweek. "His vision and his intensity and the range of influence he was drawing from—it was the Goliath of an artist." The Next Day proved to be an invigorating comeback, and the documentary captures every stage of its production, from the music to the bizarre, self-referential album art.

The film similarly tries to recreate the recording sessions for Blackstar, with saxophonist Donny McCaslin and his jazz ensemble. (Bowie eschewed a conventional rock band lineup for funkier, more experimental backing.) By then, the star was ill. Though he appeared healthy and vigorous when in the studio, Johan Renck, who directed the music videos for "Blackstar" and "Lazarus," recalls Bowie Skyping him to say that he was seriously ill and "probably going to die." "I thought for a brief second that he looked scared," Renck recalls onscreen.

The clip for "Lazarus" depicts Bowie lying in a deathbed, a bandage covering his eyes. That imagery was Renck's idea; it was not intended to represent Bowie's illness. The director only later learned that Bowie discovered his cancer was terminal and no longer treatable the same week he filmed the music video. He died two months later.

Bowie is both the subject of this film and the glaring absence at its center. (His collaborators try nobly to channel his creative energy and self-deprecating wit.) The work remains fresh in memory, but the author is not here to present it. But Bowie created a final work that speaks for itself. Blackstar is a remarkable and enigmatic farewell record, a genre-bending beast anchored by free-jazz textures and haunted imagery. The album "could stand up with anything from his '70s heyday," Whately says. "With perhaps the exception of Leonard Cohen, I can't think of another artist who was producing some of their very best work at the very end of their life." (Gerry Leonard believes that Bowie wanted to make another album after Blackstar. "I don't think he felt like that was the end.")

Fans craving insight into Bowie's creative process, including the recording of those final two albums, should not miss The Last Five Years. Those expecting intimate details of his battle with cancer will be disappointed. The documentary does not feature Bowie's family members. Nor does it make any real attempt to breach the wall that Bowie erected between his public and private lives. In any case, Bowie would have found such a film, focusing on the details of his illness, "incredibly tiresome," says Whately. "I was a fan of his music, not of his private life. He was quite a shy, private individual."

Was there anyone whose perspective Whately wanted but was unable to include? "It would have been lovely to have Lou Reed."

For Whately, the movie is the culmination of 40 years of fandom. He has been a Bowie obsessive since the late 1970s, when he raided his brother's record collection, spotted the flamboyant cover of Aladdin Sane and was "appalled and thrilled in equal measure." By the time Lodger came out, he was hooked.

What does he hope a non-fan (or new convert) might take from the documentary? "That this is a man who always was ahead of his time," says Whately. "And I hope even people who aren't Bowie fans will understand that he was trying to grapple with the bigger themes: fame, alienation, spirituality—what we're doing here, basically."