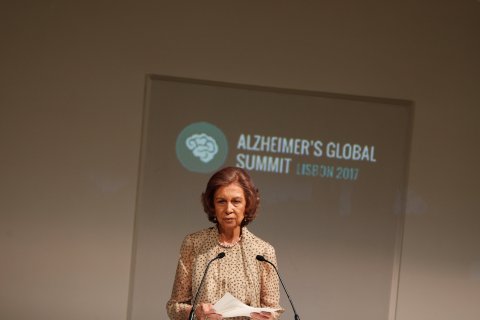

Dementia doesn't happen all at once. And it's not well understood what, if anything, can be done to reverse it. But doctors now have more ideas about what can slow down its progression and new research suggests that exercise may play a big role.

On Wednesday, in the journal Neurology, the American Academy of Neurology issued guidelines for what can be done for patients who are beginning to see signs of cognitive decline.

"If we can push it back two, three, five, years, that's a big deal," Dr. Ronald Petersen of the Mayo Clinic, a neurologist and lead author on the guidelines told Newsweek. As for the amount of exercise, Petersen says something on the order of twice a week, or 150 minutes a week should be helpful.

As they age, some people begin to struggle to keep track of important events like doctor's appointments and visits from families, or struggling to find missing words, but still far from the stage where they can't function in the world. The term medicine has landed on for this state of mind is mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and it's a stage of cognitive decline that often progresses to dementia that medical research is just starting to look at.

In order to come up with the new guidelines, which include recommending cognitive training and avoiding medication that can lead to confusion and cognitive impairment, Petersen and his team looked through hundreds of research studies. Overall, these studies found significant improvement in cognitive measures among older people with MCI who exercised.

While it's harder for people over 65 to get that exercise in, Petersen is not recommending your grandmother take on CrossFit or pole vaulting. Instead, he says, light aerobic exercise, even walking, could help. And, being realistic about people's limits, he recommends simply doing a little more of whatever it is you're doing. Maybe squeeze in an extra couple walks a week, or add five minutes to the ones you already take.

While there is a clear distinction between MCI and dementia, according to Dr. Bruce Troen, chief of geriatrics and palliative medicine at the University at Buffalo Medical School there is a 3-fold increase in risk for dementia among those with MCI.

While probably no one wants to start losing track of things, "The important elephant in the room is ... that all of us would want to prevent the progression into dementia," Troen said. And anyone who's ever opened a web browser has some notion that exercise might be good for the mind, but there are still open questions is to how and why this recommendation would work.

Troen posits that exercise might do the trick by helping blood flow more readily to parts of the brain that dementia restricts. He's also pointed out that past research has raised the idea that combining exercise with mental games or "cognitive training" might give patients more "bang for their buck."

Whatever exercise does to the brain, the guidelines raise the question: what does this actually change when it comes to people and their doctors?

Troen, a geriatrician who sees only older patients, says it won't likely change the way he practices. But Petersen says he hopes these guidelines help primary care doctors to know how to handle these patients, and to get these patients to help researchers like him. Studying this stage of cognitive decline, Petersen says, could be extremely helpful for learning to treat different forms of dementia. "If we get people who are only mildly symptomatic to enroll in clinical trials, we might be able to find ways to stop the process at this point. And that would be critical," he said.

"This is an indication of where the field of cognitive function and aging is going. Ultimately we'd like to identify people who are at risk of these conditions even when they're clinically normal."