In Merchants of Doubt, their 2010 book that vivisects bad science and industrial cynicism, science historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway decried the uneven battle for the popular imagination fought, on one side, by scientists ill-equipped for high-volume cable-TV tussles and, on the other, by the "well-financed contrarians" bent on dismantling whatever lab results, peer-reviewed theories and settled science might lead to even the most benign corporate regulations.

The authors unraveled the deny-and-obfuscate tactics concocted in the 1950s by Mad Men and Big Tobacco to cloud understanding of what even the proto-mainstream media was beginning to grasp. "Cancer by the Carton," read a 1953 headline in Reader's Digest. "Doubt," countered a public relations memo exhumed decades later from Big Tobacco's yellowed files, "is our product."

And doubt, argued Oreskes and Conway, became the mantra for purveyors of acid rain, ozone holes and, most significant, global warming. Keep the cigarettes burning, the CO2 combusting and the profits flowing for as long as possible.

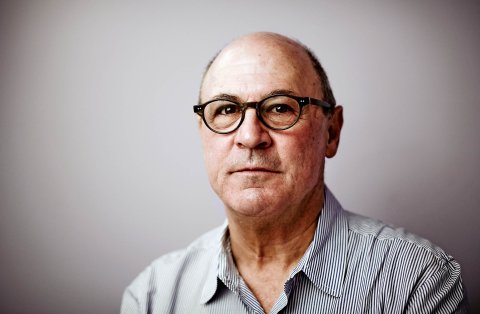

Joining the fray is filmmaker Robert Kenner, whose surprisingly rollicking screen adaptation of Merchants of Doubt opens March 6 in New York and Los Angeles. It's a worthy follow-up to his 2008 Oscar-nominated Food, Inc., which arrived when Americans were primed to point fat fingers at Big Agra. This time, Doubt lands amid a national debate over science—legit, pseudo or just plain bad—that intensifies with every foot of Boston snow or new case of Disneyland measles.

Along with corporate greed and Madison Avenue chicanery, Kenner's film exposes a devoted and long-lived cadre of scientists (and their philosophical descendants) who established their careers during the A-bomb era and the Cold War's Big Science rivalries. Anti-communist ideologues, well-trained and often brilliant scientists such as physicists S. Fred Singer and the late Frederick Seitz saw (and see) corporate regulation as a pathway to socialism, an endgame more fearsome than any secondhand smoke or patchy ozone.

Kenner spoke toNewsweek as he was heading for the Ambulante Documentary Film Festival in Mexico City, the latest stop on his festival circuit after Telluride, Toronto and New York. He was prepared, he said, for more of the anti-science vitriol documented in his film. "It's pretty amazing, this anger out there.… I'm going to be attacked. I just hope it only takes the form of written words."

When I read Merchants of Doubt, I didn't think, Wow, great cinematic potential. What did you see there?

I didn't think it was a movie, frankly, but it led me into an arena. And actually, very little of the book made it into the movie. We used the general thesis, which is all about regulations and what is done to stop regulations—this thinking that the free market knows all. A perverse form of capitalism has taken over.

When the Freds—Seitz and Singer—popped up in the movie, I thought, Didn't they read the book? How did you convince them to participate?

Well, Fred Seitz had died [in 2008], so the footage we used of him was from many years ago.... When I met Fred Singer, he told me he was doing a book on food and pesticides and he thought we could collaborate. I said, "What's the name of your book?" and he said, "Pesticides Can Save the World." I said, "We really are coming at this from very different angles," but that didn't deter him whatsoever. My impression is that he thinks he can win people over.... I'm hoping to represent him in a way he presented himself to me.

Many of these people, including Fred Singer, worked for [Big] Tobacco or were funded by Tobacco and went on to work on numerous other issues, including energy and climate, and used the same arguments they had used for Tobacco. Singer is an ideologue. I think he's made some money at it, but I make money, we all make money. I think his motivation was a real fear of communism. He was a very good scientist, and Fred Seitz was a major scientist who had done very impressive work. You get those few credible scientists who are ready to pervert their understanding of science to favor their ideological beliefs, and it creates a rocket that takes off. It leads us into this strange territory of the anti-Enlightenment.

It's hard not to come away without some admiration for them.

I really get offended when people on the left say, "Oh, these people are so stupid." They're not stupid. They're really smart. Tim Phillips [president of Americans for Prosperity, the conservative political action committee] is really smart. He's able to go out there and deliver this message, and he makes money for the Kochs. Marc Morano [climate change skeptic and frequent Fox News interviewee] said, "Our job is simple. All we have to do is stop action." I think he's very funny, he's very smart. And I wish he was backing other things.

What are the differences between the left's use of science and the right's use of science?

There is some bad science all around. In Food, Inc., I attacked the fact that there was no labeling of GMOs [genetically modified foods], but I didn't say GMOs are evil. I am suspicious of Monsanto's business practices, and I think if you have a product you are proud of, you should be open to promoting it, not hiding it. I might not like Monsanto's business practices, but I'm not going to totally tear apart everything they're saying about GMOs.

But I think because regulation has fallen into disfavor, [science skepticism] has become much more of a calling card for certain corporations and certain conservative or libertarian forces at the moment. But there are incredibly good, smart people who merely have different economic ideas than I might have, and different solutions. They're ready to recognize the problem of climate change and want to debate the solutions. That's where the debate should be today.

So you're optimistic that we're moving from a debate over the existence of climate change and toward a debate over solutions?

There is no debate about the existence! The media has been partially responsible for implying there's a debate on climate change. There are great debates to be had on solutions. When I say we should have a Manhattan Project on climate change, people like Bob Inglis [a South Carolina Republican who lost his congressional seat after disavowing climate change denial] or many brilliant conservatives might say, "No, business can solve this problem much more rapidly [than government]." I think business could be a great part of the solution, but you can't dump your garbage in the air and expect to get rid of it for nothing. We have to start to pay real prices.

Toward the end of the movie, you show a house with beautiful Christmas lights on it. The shot suggests that things people love will be taken away from them.

I look at those Christmas lights and I think, [Ronald Reagan's secretary of state] George Shultz has solar panels and drives an electric car. And when he sees my car he says, "How can you drive that gas car?" I got shamed into changing, and it wasn't easy. I got solar panels, and it took a lot of work to get them. If it weren't for George Shultz, I might have given up. It's hard to change. As Bob Inglis says, we want climate change to not be true. Shultz is saying, "Hey, you can have solar panels, and it only costs 10 percent more than putting regular tiles on your house." If you can price things in the marketplace correctly, these things will come about rather quickly.

How did you make a film about global warming entertaining?

First of all, I don't think it is about global warming. I think it's about people who create doubt. Their next big payday just happens to be climate change. It used to be tobacco. But the movie Thank You for Smoking was a bit of an inspiration. The other inspiration was Marc Morano, who is really funny, really quick. At the same time, I think when Marc Morano attacks scientists, there's a cost to the scientists' lives and to their research, so I wanted to point that out.

What do you want people to come away with?

We say in the film, "Once revealed, never concealed." Listen, we're not going to convince a third of the audience, but I think there are people who are just confused. I wanted to show that the tobacco representatives, when they talked about tobacco, were lying to us, and they got away with it for many years. I'm hoping that when you see many of the same people using much of the same language today, you'll start to look at this issue of climate change in a different way. And I would hope that newspapers stop presenting deniers as scientific experts. I think the news networks should be embarrassed to do that.

Archival footage in the film includes a hospital patient smoking in her bed and children playing in clouds of DDT. What images will we be looking at years from now, wondering, What were we thinking?

Senator Jim Inhofe saying, "Look, it's snowing—global warming is not happening." These guys are not going to look great to their grandchildren.