Boris Nemtsov, the Russian opposition politician shot four times in the back and killed while walking across a Moscow bridge late on February 27, lived in a large apartment directly across the river from the iconic domes of St. Basil's Cathedral. The last time I saw Nemtsov was in that apartment, nearly five years ago. I was reporting a lengthy article on "Putin's oligarchs"—the men surrounding the president who had become the richest and most powerful businessmen in the country. Many, like Putin, had worked for the KGB.

We had a long talk—more than an hour and a half. Nemtsov's political party was about to release a report his researchers had put together on corruption in Putin's Russia. He had a lot to say, and was, as usual when talking to the press, ebullient. He was as handsome as ever, dressed incongruously in a bright lime green sweater and light khaki pants. I remember thinking he looked as if he had just come off a yacht in Sag Harbor or Newport Beach. After our conversation, Nemtsov showed me around the large apartment, pointing out a few mementos from his time in government.

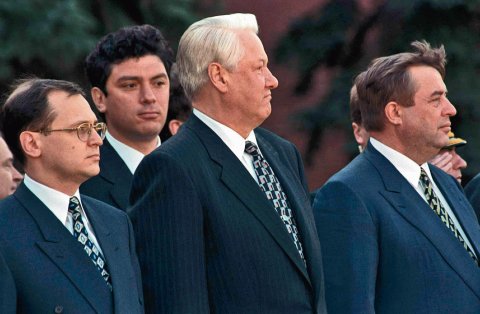

He had come to prominence in Russia after Boris Yeltsin's re-election in 1996. He had been a young, reformist governor in Nizhny Novgorod, about 250 miles east of Moscow, when Yeltsin sent for him to come to the capital. He was appointed a first deputy prime minister, with a powerful portfolio that included huge swathes of the Russian economy, including energy. One of his jobs—his main job, arguably—was to tame the oligarchs of that era.

Oligarch had become a term of art in Russia in the 1990s, when I was bureau chief for this magazine in Moscow. Back then, oligarch referred to the men who were able to buy valuable state-controlled companies for ludicrously low prices. The idea—defensible—was to reduce the government's role in the economy, and get important industries like energy, telecommunications and autos into private hands. It was, indeed, the fundamental principle underlying the transition from communism to capitalism, as a man named Anatoly Chubais, then Yeltsin's chief economic architect, used to explain to anyone who would listen.

But there was also a political component to the tremendous transfer of wealth then under way in post-Soviet Russia. The men who benefitted from the schemes to privatize the economy—the oligarchs—in return supported Yeltsin's re-election. Yeltsin, the hero of the Russian revolution in 1991, was running against a dreary Communist hack named Gennady Zyuganov. Chubais felt he could drive a stake through the old system's heart if Yeltsin won the election, and if the resources of the newly minted billionaires in Moscow were needed to do it, so be it.

Yeltsin won the election, despite the fact that late in the campaign he suffered a heart attack that was completely covered up by his palace guard. By early 1997, Chubais, who had effectively become Yeltsin's stand-in when the old man fell ill, knew things had to change. He and Nemtsov—who used to rail in those days about "bandit" capitalism—would be the pit bulls.

During his time in office Nemtsov had a reputation as more of a show horse than a workhorse—one of his early initiatives was to get government officials to give up their Mercedeses and ride around in cars made in Nizhny Novgorod. That reputation may have been a bit unfair. He did, after all, have a go at the oligarchs. In April 1997 he met individually with the seven most powerful of them and declared that the rules were going to change. No more rigged auctions for state assets. As David Hoffman, then the Washington Post's bureau chief in Moscow wrote later in his book The Oligarchs: "It was all nice talk. In fact, Nemtsov was suggesting nothing less than dismantling the system of oligarchic capitalism that had taken shape under Yeltsin, Chubais and the tycoons."

That year, Nemtsov was Russia's rising star: young, charismatic, and apparently Yeltsin's favorite—the son he never had. The whispers soon became that Yeltsin wanted him to be his successor. (Think now, in the wake of his assassination, of the irony in that.) He was gregarious and had a populist's touch with the people—the opposite of the brilliant but technocratic Chubais. George Soros, who had stayed away from investing in Russia, liked Nemtsov sufficiently well that he changed his mind.

The moment of optimism came and went quickly. Russia's oligarchs—and the government—got bogged down in a vicious fight over the privatization of the nationwide phone company (the oligarchs having apparently not gotten Nemtsov's message that these types of deals would no longer be rigged). Then, in 1998, came the financial crisis, when Moscow had to default on its massive debt and devalue the ruble. The government was discredited, and Nemtsov soon gone.

The following year, an ailing and increasingly out of it Yeltsin named an obscure former KGB operative from St. Petersburg, Vladimir Putin, as prime minister. Then, on New Year's Eve, 1999, as the new millennium dawned, Yeltsin resigned and Putin became acting president. Nemtsov would co-author an opinion piece in The New York Times that captured the sense of exhaustion the tumult of the Yeltsin years had generated. Like me, like the U.S. ambassador to Moscow at the time, Jim Collins, like then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, like so many others, Nemtsov said that at least Putin was young, energetic and perhaps competent. "Russia could do considerably worse than have a leader with an unwavering commitment to the national interest. And it is difficult to see how we could do better," he said.

Nemtsov soon enough would be cast into opposition—an opposition that became less and less relevant in Russia as Putin tightened his grip and showed who he truly was. Last month, as he walked home around midnight across the bridge, across from the beauty that is St. Basil's, he was just two days away from leading an opposition march to protest Putin's war in Ukraine, and of releasing a report that purports to show evidence of direct Russian involvement in the invasion—something the Kremlin has steadfastly denied.

As we walked around his grand apartment across from the Kremlin that late afternoon several years ago, one detail grabbed my attention: a photograph of Nemtsov with the old man. Yeltsin, once he stepped down, was rarely seen in public again. This was a shot taken at adacha outside Moscow, where Yeltsin would live out his days until dying in the spring of 2007—exactly a decade after he had plucked the young man from Nizhny Novgorod to come help him in Moscow. In the photo Yeltsin is smiling, but he is frail, his face thinner than it used to be, his thick white hair now wispier. Nemtsov smiles too, with a touch of gray around the temples, handsome as ever. You can't look at that photo and not be touched by the obvious affection between the two men, and be saddened by what might have been.

We now know what a "leader with an unwavering commitment to the national interest" can and will do. Russia's fledgling democracy effectively snuffed out; wars in the former Soviet republics of Georgia and now Ukraine; journalists and opposition figures murdered or imprisoned. Where—and how—does this end?

In her famous account of the gulag under Stalin, Journey Into the Whirlwind, the author Eugenia Ginzburg spent 18 years in the Soviet prison system, and when she got out she wrote: "Was all this imaginable—was it really happening, could it be intended? Perhaps it was this very amazement that helped to keep me alive. I was not only a victim but an observer also. What, I kept saying to myself, will come of this? Can such things just happen and be done with, unattended by retribution?"

That's the question that hangs, right now, in front of men like Barack Obama, and David Cameron, and women like Angela Merkel—the leaders of the West, now weak and divided and distracted by lots of other very real problems: "Can such a thing just happen and be done with, unattended by retribution?"