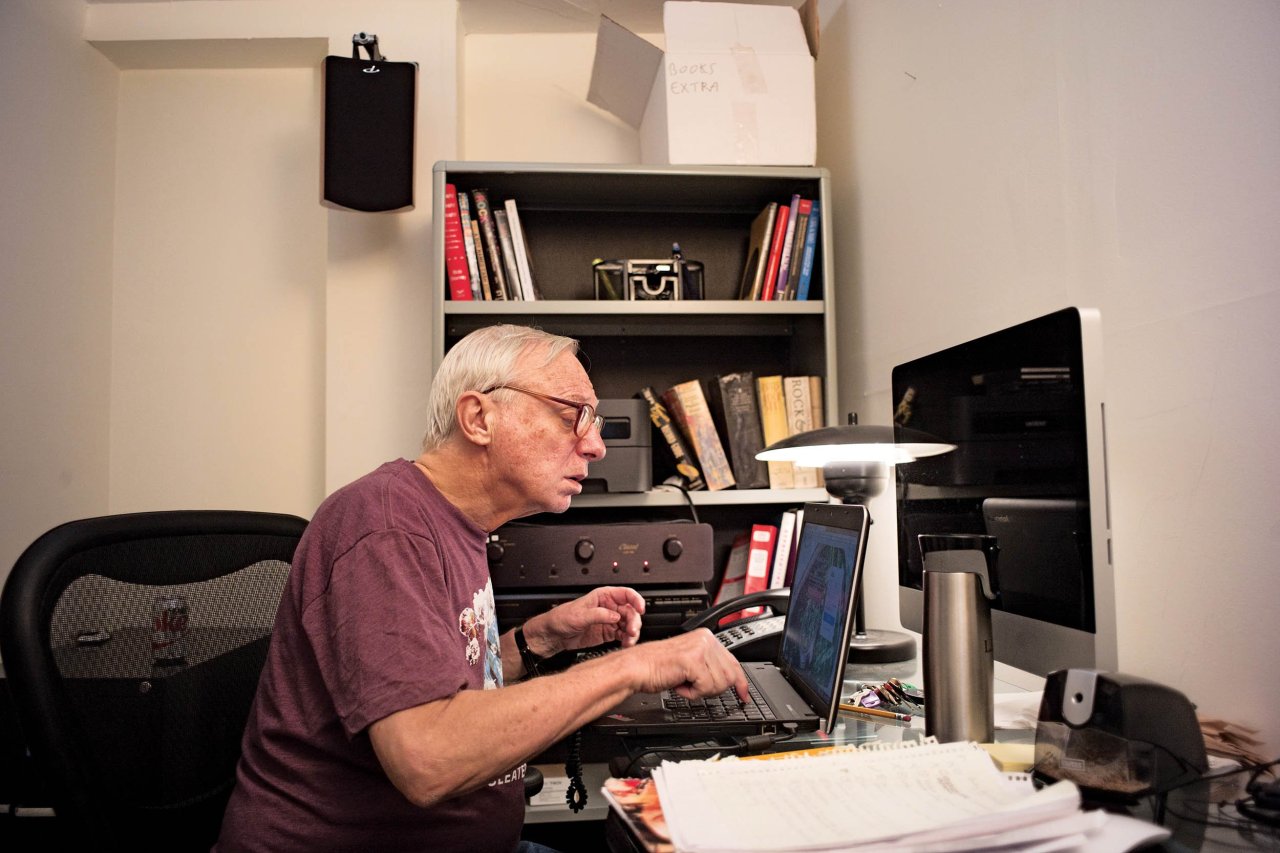

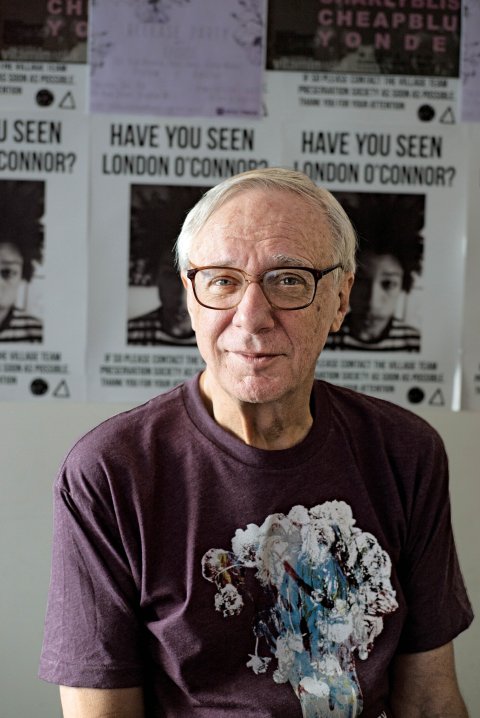

The Dean of American Rock Critics is frazzled when I call. He's so busy with interviews and book events that he hasn't managed to read the New York Times review of his new memoir, Going Into the City. "Mixed, I'm told," Robert Christgau tells me. "I haven't had time to read it. It's in my bag." Does he want to take a minute and read it now? "No, no, no, no, no"—there'll be time for that later.

"It's my 15 minutes here," Christgau adds, which is a weird thing to say when you've been writing professionally about music and pop culture for nearly as long as the president has been alive. As the longtime Village Voice critic, Christgau made a name for himself—and enemies like Lou Reed—with record reviews that were terse and notoriously unforgiving, though Going to the City matches neither adjective. The "Portrait of a Critic as a Young Man," as it's subtitled, finds a kinder, gentler Christgau reflecting on his Queens upbringing, his romantic entanglements (including a '60s involvement with the late New Yorker writer Ellen Willis) and the first decade of his Voice career, when CBGB ruled New York and The Ramones and Talking Heads ruled CBGB.

Christgau spoke by phone with Newsweek about the research process, today's rock writing landscape and why people should stop being so prudish about the sex that's in his book.

How do you like being on the other end of the interview cycle?

I've never been much of an interviewer so I don't think of it that way. It's fine. I like it. But given that I have this teaching job and I'm trying to churn out my Medium piece and edit my wife and do a lot of other things, it's very hectic. It's my 15 minutes [of fame] here. And sometime next week it'll end and I'll probably miss it a little and not miss it a little… I could see how celebrities get the way they are, you know? If you lived this way every day, how the fuck would you know what life was like?

In a sense, you can't blame them for having a warped sense of reality…

Well, yes you can. [laughs] But you have to qualify it. Contextualize it.

You've been writing professionally for roughly half a century. You have so many stories. Why'd it take so long to publish a memoir?

First of all, I don't think there's a whole lot of my writing stories in the memoir. It's as much personal as it is professional. It's about art first. But love comes in a close second. And I don't just mean romantic love, although that's the main thing. I mean my friends in general. I don't know any celebrities. I know a lot of people that most people have never heard of. And the book is really about them. That's always the world I've lived in. Since I sold my story, that was a story I could tell. And that's the story I did tell. That's how I feel about it. From what I understand, [New York Times critic Dwight] Garner was disappointed I didn't tell the other story.

Stories about hobnobbing with celebrities?

It really is stupid to talk about this. So let's not talk about what I think his review said. That really is foolish. I couldn't tell star stories. I put four of my star stories into one paragraph. If I were to tell you all the details, I'd be making shit up, as I put it in the introduction. I do suspect that a lot of people who do that—and they're going back 30, 40 years—that they are making stuff up. But even so, do people really remember all the details of their lunch?

And dialogue...

And the dialogue especially! I say in the introduction that there's very little quoted speech here. Because I would be making it up, and in a few places I did make it up! I had to! Some of those quotes really are phrases that have stuck in my mind, which doesn't absolutely guarantee their accuracy. But at least it moves in that direction. But there are a few cases where I didn't really remember exactly what was said but I needed language. There's a scene when this woman Ann who I had this extremely brief affair with tells me that she doesn't want to see me anymore. That language I don't remember. I had to make it up. I did my best. But it could very well—linguistically, not sense-wise—be wrong.

Tell me about the research process.

It was a matter of reading a lot of letters. The college chapter, which is full of little details—I don't remember those details! They were in my letters, and I assume I wasn't lying to my girlfriend. Because I don't lie to anybody. In the wake of my breakup with [late New Yorker critic] Ellen Willis, I had another bunch of letters. Actually, there were more than I read. I'm sure that had I read that other 15,000 words—which would have taken me a day—that I would have had a few more juicy details that fit the story. That's what kept happening. While I'm writing Miriam about whether I love her or not, I'm also talking about what lecture I attended. "Oh yeah! That lecture! That's where I found out about existentialism."

And you tracked down people who are featured in the stories?

I spoke to almost everybody who's alive. There are a few exceptions. Like, I would have loved to have spoken to this woman Sue who I went out with briefly after I broke up with Ellen, because I've wanted to talk to her for a long time. Because I feel bad about it. And I can't find her. I hope she's still alive, and I don't know that she is. But yeah, I tracked people down, again and again and again. And it always helped. Even if they didn't remember the thing I was talking about at all, they gave me a better sense of place.

You kept up your reviews while doing all this.

I kept up the rest of my career. Crucially, I was not teaching full-time then. That would have killed it.… Now I have a full-time position, so doing all this work and teaching, it's impossible. But I've done a lot of things that I was told were impossible. I was told it isn't possible to write a book while doing other writing. That's completely not true for me.

You're obviously credited with making rock criticism into a professional job. It seems like it's increasingly harder to make a living from criticism. Do you worry the critic is a dying breed?

I worry about it. You know, criticism began as the province of amateurs, of wealthy men who liked the arts. And I worry that we're moving into the—I'm just going to say "modern," not "postmodern"—the modern equivalent of that. The contemporary equivalent of that. Which is a somewhat different economic situation. Society isn't as stratified as it was in the late 1600s. But there still is a lot of people with leisure, and of course you have this publishing platform that's so easy to use. I don't know who they are, but every once in a while I trip over one. And sometimes they're pretty good.

A Web writer?

Yeah! I don't read enough music criticism these days. One of my many—it's not going to be my New Year's resolution, it's my "term-end resolution." When the term is over, I'm going to do A, B, C and D, and one of them is write music criticism.

Write or read?

Did I say "write"? Read. I'm sorry. Read more criticism and get a better sense of the landscape. There are places like Grantland and Noisey that I barely look at. Now I read criticism when I need context. When I'm writing about a record and either it's so old—because I don't come in early on these things—that I don't want to repeat what other people are saying, so I try to found out what that is. And get some facts, because half the records I review I didn't get from a press agent, I bought them. Then I have to figure out who the fuck this is. And journalism helps.

But it's completely random. I don't read any magazines. My observation is that Pitchfork, long the gold standard of Internet music journalism and long, in my opinion, the home of an enormous amount of truly dreadful writing, has become much better in the last, say, three or four years. Before then, it was the one place where if you wanted to know what city the band was from and what the three best songs this guy thought were on the record, you could guarantee to get it there. Because there's no place else online where they are guaranteed to do that. They're not paying them, they're amateurs, they're doing what they want. And so there are no professional standards at all and some would be of great use. Pitchfork, I think, has really improved. Grantland, Noisey, Consequence of Sound—those are places I at least want to be looking at because the quality that I do run across is pretty good.

Do you still read the Voice?

No.

Never?

Essentially. I mean it's not quite never. But it's not more than four times a year.

Are there any critics specifically who you make a point to read?

No, there is no critic I make a point to read. Not even [NPR music critic] Ann Powers, who I absolutely adore and think is now the most important rock critic in the country. I don't read her regularly. That's another thing I would do: figure out how to never miss Ann's pieces. Because I'm not on Facebook and I don't even know when her pieces appear. I'm not that Internet-savvy. I get by. But that's all. I don't have serious skills or any other stuff.

You have started using Twitter recently.

Yes, I started using Twitter in part because I had to publish a Medium Cuepoint. But also because a young friend of mine named Zach Baron especially—and other people, too—had convinced me that Twitter was much better than Facebook. Everything I know about Facebook makes me want to avoid it. Twitter has really improved my reading habits. These two guys, Zach Baron and Jon Dolan, both of them I follow. They never tweet! They have a feed, and they find out what they're going to read from that feed. I use it half and half. I decided if I was up there, I should tweet a little bit.

I noticed last week some other writers were calling you sexist on Twitter.

Most of that stuff doesn't reach Twitter, and to be honest with you, Zach, I don't want to talk about it because I don't want to alert them to the fact that I don't read it.

You don't want to alert them to the fact that you don't read what?

I know that this stuff is happening. I've seen very little of it. And I would just as soon, although I know I may not get this request honored, that it not be mentioned. Because I don't want to fire them up and have them…mad that they didn't succeed in getting in my face, which I think they would really like to do. They haven't gotten in my face. I know about it. I haven't read any of it. I haven't read Dwight Garner's review! [laughs] Which should definitely come first.

I will say two things. As I say, I know I can't go off the record on stuff. But I do my very best not to fire such people up. I'm very successful at ignoring them. I would say two things. The business of my supposedly outing Ellen Willis's rape? Ellen Willis's rape was outed by her daughter in a New York magazine interview in April of 2014. And I was sufficiently concerned about that particular paragraph—not the whole chapter—where there's lots of other private stuff that I thought was my business. And her husband had always told me [it] was my business—Stanley Aronowitz. But I sent the paragraph about the rape to Stanley, telling him that if he thought I should take it out I would, and expecting that that's what he would do. Instead, he encouraged me to leave it in. So I did.

I did vet that. And I vetted a few other private things that I don't want to name. But there are a few other cases where I went to people who I thought might be embarrassed by something I said and got permission. One place I was encouraged to tone it down, I did.

What were you encouraged to tone down?

I'm not gonna tell you.

There is quite a bit of sex in the book.

You know, I don't think there's quite a bit of sex. I think people are being squeamish. I don't understand what the deal is. I'm writing about love. Maybe they're squeamish about writing about love. Or they think my love life is no more interesting than anybody else's, so why should I get to write about it? Which may well be true, only I get to write about it because I'm a good writing and I'm writing this book, that's why. It may not be true. I'll leave that to others to judge.

I believe that romantic love between a man and a woman—or for that matter between a man and a man or a woman and a woman—usually involves sex and, in my personal experience, ought to involve sex. You can't write about sex by generalizing about it. Or assuming everybody knows. Because that simply isn't true. I think there's an enormous amount of squeamishness about this subject, which is shocking in 2015! It shocks me. Because I do see it as priggishness, prudishness, squeamishness. And I tell my students, writing should be clear, compact, concise and concrete. That seems like Writing 101. Maybe Writing 1. So! If you're going to write about sex, then you have to be concrete!

There's not a lot of sex in this book. There are sentences here and there! And it's not pornographic. Because I know what pornography is. I like pornography. It gives you a hard-on. This isn't going to give anybody a hard-on, unless people get hard-ons about my prose. Which I hope they do.

You write about seeing bands like Television and Patti Smith at CBGB in the '70s. Do you think there's a scene in New York today that's even remotely comparable?

Even worse than music journalism, another one of my term-end vows is going to be going out and seeing more live music. I've seen very little live music in the past six to eight months. And I'm certainly not inclined to frequent the Brooklyn club circuit, which is where I'd find this stuff.

Meaning Williamsburg?

I don't even know! I know it's out there. I don't know where it is. I hear tell of it. I've only been to the largest of those clubs, I think. Knitting Factory, and that place out wherever it is, near Smith and Ninth. I don't even remember what it's called. The Bell House? And the place that used to be North Sixth and is now something bigger.

CBGB was a very special instance in my club-going experience. As I think I say in the book, it's the only place I ever hung out. The only place I ever really visited casually to see what was going on.

What's the last great show you went to?

Now? Do I need to look it up? Oh, hell. I'm terrible at this. And, in fact, I didn't write about the last show I went to. I keep a diary. You could also ask me what records I'm listening to now and I wouldn't be able to tell you either. [laughs] Shit! I saw a really good show. When was it? There was Wussy. That was the show, actually—Wussy. I never miss them. It was a little rough, actually, but it was also a little ambitious and the best crowd I ever saw them draw. And I'm gonna go see Sleater-Kinney tomorrow night and I'm really looking forward to it. And I'm gonna try and see Action Bronson in March. Somebody invited me.

If people invited me more, I'd probably come more. But I don't get invited to big shows. When I was the Village Voice music editor, I could go wherever I wanted pretty much. But I was only music editor until '85. Even as just the chief critic, you'd have to wheedle sometimes. I never found that process a very pleasant one.