Mallory Heiney, 21, owes $20,000, a debt she took on to attend a for-profit college she says scammed her and thousands of other students. And she isn't going to pay anymore.

Heiney and 14 other students from Everest College, one of the for-profit schools that belong to the Corinthian Colleges Inc. brand, declared a debt strike on Monday. The federal Consumer Financial Protection board alleged in a lawsuit last year that Corinthian lured students with "bogus" job-placement statistics and saddled them with predatory loans, even going so far as to "strong-arm" students into making loan payments while still in school.

By declaring a strike, the students effectively formed a new kind of union—a debtors' union—that they hope can lead to negotiations with a loan system that doesn't typically negotiate. Most of their loans are owed to U.S. Department of Education—so while one branch of the government has said the loans were predatory, another is still trying to collect the money.

Americans are drowning in student loan debt. As of last year, 40 million people in the U.S. owed a combined $1.2 trillion to banks, lenders and the federal government for their educations. For the many who find themselves unemployed or stuck in low-paying jobs after college, there's often no way out. Student loans aren't dischargeable, even if you go bankrupt.

The 15 Everest students are working with Strike Debt, a group of economic activists that emerged out of Occupy Wall Street. Strike Debt recently launched its latest project, called the Debt Collective, to support the students in their strike and encourage others to do the same. "If you owe the bank thousands of dollars, then the bank owns you. But if you owe the bank millions, then you own the bank," their website reads. Debt Collective is organizing legal support for the students to fight consequences of refusing to pay their loans, such as having their wages and tax returns garnished, and their credit ratings going down. But the students say they're willing to take that risk. They want all their student loans—private and federal—forgiven outright.

Heiney, from Tecumseh, Michigan, found herself saddled with $20,000 in debt and a low-paying job after completing a one-year nursing program at Everest College last year. She says the consequences of going to a Corinthian school cut way deeper than even what the federal government has uncovered.

In 2013, Heiney returned from a mission trip to Guinea that she says inspired her to pursue a career in nursing. She called Everest's campus in Grand Rapids, Michigan, to ask questions about its program.

"As soon as I showed any interest in them, they jumped on my back. They called me kind of relentlessly. When I came to look at the school, they put me right in front of a computer and had me start filling stuff out. They told me I was a really good match, and put all these things in front of me, [saying], 'Here's what you could be making in a year.'" Heiney says she later learned the employment statistics they showed her were false.

She enrolled, and things started smoothly. But within less than a year, Corinthian announced it was in a financial quagmire. (Later, it would shut down the Grand Rapids campus.) Suddenly, her professors stopped showing up: "They started dropping like flies." But classes weren't canceled: Instead, she said students were often told to write their names on a piece of paper for attendance and go home. Heiney says she passed her state nursing exams only because she taught herself the material outside of class.

Heiney graduated from the one-year program in August, $20,000 in debt. That's when trouble really began. Potential employers, she said, would hardly look at her.

"When you go into an interview, you have to go at it like [the Everest degree] is a criminal background. You have to convince people to hire you despite it," she says. "You want to be proud of your education, but you're on a blacklist. I tried to sign up for a community college and they said that my credits won't transfer. You're at the bottom of the educational totem pole.

"It was kind of a big ol' smack in the face."

Not only was Heiney struggling to find work, but her student debts began coming due, and she couldn't pay. "You feel like you're being hit by all these waves," she said. She finally found a job in home health care that she began this week, but it wasn't thanks to her degree, she said.

Corinthian denies all claims that the education it offers is of poor quality, or that it engaged in unscrupulous lending practices. "We stand by the quality of our educational programs and are proud of our results on behalf of our students," said Joe Hixson, a spokesman for Corinthian, shortly after the news of the strike broke.

Heiney came across Strike Debt when Ann Larson, one of the organizers, posted on a Facebook page run by Everest students. The idea of a strike immediately appealed to her, despite the risks.

"We are educated on the legal repercussions. But the fact is, we're already going through these things. We have this on our backs that we went to Everest. I can't get a job without explaining I'm actually smart. The risks? Yeah, they're big. But what we're trying to do is far bigger. This is something that needs to be done, and something that we're not scared of."

"Short term, I want the people who have been wronged by this to get freedom. I want them to finally be able to breathe and move on from this. Long term, it's about the Department of Education."

In 2010, Corinthian was one of the largest for-profit college chains, with more than 100,000 students at over 100 campuses and attending programs online. But this year, the Massachusetts and California attorneys general sued the school in separate suits, alleging that it distorted job placement rates, pressured students to take on huge loans and requested they begin repaying them before graduation. The U.S. Department of Education recently stepped in, facilitating the sale of more than half of Corinthian's campuses to a nonprofit arm of the ECMC Group, a student debt collection agency. (Corinthian is still in charge of the remaining campuses, though it intends to either close or sell all of them. A spokesman for the school says there is no specific timeline for those changes.)

The Consumer Financial Protection Board then secured debt relief for some Corinthian-affiliated private loans. But the vast majority of the debt—mostly in the form of federal loans—remains on the backs of the former students.

In December, Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and several other Democratic senators wrote a letter to Education Secretary Arne Duncan, urging his department to discharge federal loans for Corinthian students.

"The dramatic collapse of Corinthian Colleges, Inc. as a result of mismanagement and allegedly fraudulent activity has not only undermined the educational credentials and aspirations of hundreds of thousands…it has also left them burdened with millions in outstanding debt. Congress anticipated this problem when it provided avenues for relief from overwhelming debt taken on by students at duplicitous colleges," Warren wrote. "These legal tools, however, are of little value unless the regulators at the Department of Education actually use them."

Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healy sent a similar letter to Duncan this month. Denise Horn, the assistant press secretary for the Department of Education, wrote in an email that the department is "working on a response" to their letters.

"The Department shares the commitment of Senator Warren and Attorney General Healy to upholding the rights of students who may have been harmed by the actions of institutions that participate in federal student aid programs," she wrote.

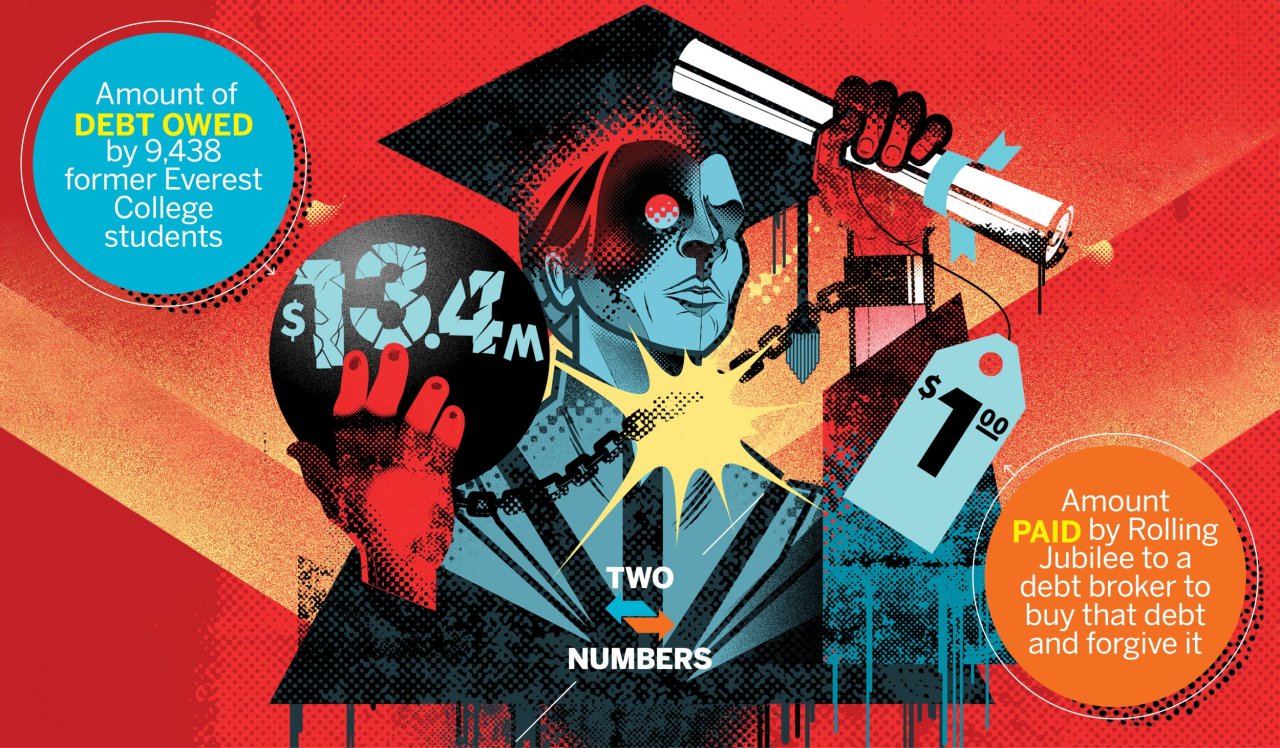

Meanwhile, another arm of Strike Debt, called Rolling Jubilee, just bought and erased $13.4 million worth of student debt, abolishing the private loans owed by 9,438 former Everest students. They bought the debt for a mere $1 from a debt broker on the secondary debt market. The activists agreed to a nondisclosure agreement that bars them from revealing the name of the broker, but according to Astra Taylor, a Jubilee organizer, the broker gave up the debts because he felt they were too "ethically toxic" to collect on.

This is the third major student debt buy for Rolling Jubilee, which in 2012 canceled $15 million worth of debt from medical bills, and last year canceled $3.9 million in student debt, also from former Everest College students. On both occasions the group took advantage of the secondary debt market to buy debts from brokers for pennies on the dollar. When loans are left unpaid for long enough, lenders will eventually cut their losses and sell the accounts to debt brokers for a fraction of the value of the original loans. Technically, anyone can buy this "distressed debt," so long as they are an incorporated company.

Rolling Jubilee, which is registered as a 501c4 non-profit, purchased the debts from brokers in bundles. The bundles are labeled with the name of the organization to which the money was originally owed (making it possible to buy debts specifically owed to Everest College, for example), but they're otherwise anonymized, so it is impossible to know the identities of the individual debtors until after the purchases.

"It's an awesome thing to send letters to people that say, 'Here's a no-strings-attached gift. But we also know that it's treating the symptom and not the disease," says Taylor. "The bigger point is that the Department of Education is just being relentless."

That's where the debt strike comes in.

"If I could really have it my way, I would have all for-profit schools shut down," says Latonya Suggs, 28, who joined the strike this fall. Suggs is $63,000 in debt after completing a two-year program in criminal justice at Everest. After she graduated, she learned she wasn't qualified to be a probation officer in Ohio, where she lives, even though that was the job she thought she was training for. She now works as a security guard for $9 an hour, and barely scrapes by. "I hate my job. I didn't want a job. I wanted a career," she says.

"We go into debt trying to better ourselves," she says. "I don't want other students to have to go through this."