They know the end is near, which is why the young men and women of Boyle Heights have taken to the streets with such fury, clad in bandanas, hoisting placards that leave little room for compromise. They've been charged with promoting violence and anti-white racism, but they don't care. They're in a desperate fight to keep this rise of land on the East Side of Los Angeles from becoming the next Silver Lake or the next Echo Park, formerly Latino neighborhoods overtaken by glass condominiums full of white people who have come from Beverly Hills, or maybe the hills of Arkansas.

Many of the young men and women nurse bitter memories of Chavez Ravine, a Mexican-American enclave forcibly cleared to make way for Dodger Stadium. Almost nothing remains of it 50 years later, and maybe nothing will remain of Boyle Heights either in a few years, except perhaps a plaque in Mariachi Plaza timidly describing what this neighborhood once was, before the beloved El Tepeyac restaurant became a vegan smokehouse, or just an empty storefront with papered-over windows.

And what of the people who now live there? Of the neighborhood's 92,000 residents, 94 percent are Latino, 33 percent live in poverty, 89 percent rent, 95 percent do not have a four-year college degree, 17 percent are undocumented immigrants. Where will they go? Angel Luna, a 24-year-old activist with Defend Boyle Heights, knows: "Fucking Victorville," the poor, arid plains east of Los Angeles.

There is no "Victorville" outside of London, but the residents in that city's formerly working-class neighborhoods like Shoreditch and Brixton are victim to the same forces moving with blitzkrieg speed toward East Los Angeles. They are not dissimilar from the nationalist movements now resurgent across the West, pitting a global, techno-fluent elite against less-skilled underclasses intimidated by cosmopolitan culture, with all its shows of wealth and sophistication. Gentrifying neighborhoods—whether deep in Brooklyn or on a hillside of Rio de Janeiro—are where those forces clash. Such clashes have become so frequent that The Guardian has an entire online section titled "Gentrified World," chronicling conflicts in Montreal, Moscow and Jakarta, even post-industrial Birmingham, once England's motor city.

Stopping "the economic forces of gentrification" is Luna's plan, he informed me over lunch at a Mexican restaurant off Mariachi Plaza. He spoke like a revolutionary but looked like a kid, one who hasn't had it easy, growing up in a rented apartment with his mother and three siblings. Luna now works in retail. He still lives with his family, and they still rent. A tattoo of an Aztec deity peeks out from beneath the right sleeve of his T-shirt. Enormous glasses give his face the look of an earnest student reading Marx for the first time in a Paris café as the spring of '68 comes into bloom. The whiskers and Ho Chi Minh goatee also suggest a conflict from that era. But the too-large jeans, scrunched together at the waist by a belt, seem less a function of fashion than necessity.

Little of what Luna told me over lunch—about gentrification, displacement, appropriation, capitalism—was original. Some of it seemed unreasonable, though it must also be said that he was not making these arguments for my benefit. The young men and women taking to the streets in East Los Angeles or East London frequently do not have the luxury of expensive university educations. Instead, their understanding of the issue is visceral, borne of experience. In Berlin, for example, anti-gentrification protesters hoisted a banner that said, "We don't want no yuppie flats. We are happy with our rats," words borrowed from the Dutch punk band Mushroom Attack. A poster in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn called gentrification "the new colonialism."

The surprising thing about Boyle Heights is that the neighborhood's supposed destroyers are not the builders and sellers of "yuppie flats," developers bearing plans for glass towers, real estate agents stoking hype about this, right here, being the next, next thing. For the most part, those moneyed interests have watched this battle from the safe remove of the West Side, as activists target an unlikely foe: artists.

Defend Boyle Heights has targeted 10 new art galleries on South Anderson Street, a formerly industrial strip along the desolate eastern bank of the Los Angeles River. Activists say the galleries are a proxy for corporate interests, especially those of high-end real estate. After the galleries will come the coffee shops and bars, and after that, the restaurants that serve bacon in cocktails. After that, unkempt lots empty for decades will be boxed in construction plywood, and then there will be many hollow promises of affordable housing. And then it really will be time for "fucking Victorville."

The above process is known as artwashing, which has come to widely describe displacement efforts in which the artistic community is tacitly complicit. The term appears to have first been used in mainstream media in 2014 by Feargus O'Sullivan of The Atlantic, in an article about a tower in once-destitute East London that had been redeveloped for high-paying tenants. They were being enticed, in part, by suggestions that they wouldn't be gentrifiers but, rather, original members of a new artistic community. "The artist community's short-term occupancy is being used for a classic profit-driven regeneration maneuver," O'Sullivan wrote. He labeled the process "artwashing."

Yet for many the notion of artwashing is no less urban myth than alligators in the sewers of New York. Several studies have concluded that art galleries do not displace low-income residents, but Defend Boyle Heights and the Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement (BHAAAD, pronounced "bad") don't care about academic urbanists' peer-reviewed studies. They know the galleries are a cancer that must be eradicated, for they are "enemies of the people," as Luna called them. "I want these galleries to get the fuck out of Boyle Heights," he said, finally managing a bite of food.

The course of chemotherapy recommended by Defend Boyle Heights is relentlessly aggressive. Someone shot a potato gun at the attendees of an art show, and someone spray-painted "Fuck white art" on the walls of several galleries. Like the Battle of Stalingrad, this is a furiously contested, block-by-block affair. Both sides have suffered painful losses: the closure of Carnitas Michoacan #3, a 33-year-old eatery beloved for its nachos, the shuttering of PSSST, one of the Anderson Street galleries.

When PSSST announced it was leaving in February, the activists rejoiced. "We will not stop fighting until all galleries leave," proclaimed a statement issued by Defend Boyle Heights and BHAAAD. "Boyle Heights will continue to fight against the false promises of development and community improvement that are supposed to benefit us, but end up displacing us from our home."

As we finished lunch, I asked Luna if he supported the kind of vandalism and harassment that PSSST's owner said pushed them out.

"We are not in the position to shun righteous community outrage," Luna said.

I asked if Defend Boyle Heights supported violence against gallery owners.

Such a denunciation would have been easy to make and probably smart public relations, but Luna refused to do it, referencing once again a community response that was beyond his control. He wants the artists afraid. Even more, he wants them to leave.

Tacos and Pastrami

Until recently, Boyle Heights was the opposite of hip. Known as the Ellis Island of the West Coast, it promised refuge to newcomers to Los Angeles who were prevented by housing covenants from living elsewhere. You can still see the remnants of the Jewish settlement in the Breed Street Shul, which opened in 1923. The nursing home on South Fickett Street was once the Japanese hospital. There is a Serbian cemetery, long populated by a brood of "mystery chickens" that inexplicably appeared some years ago on the graveyard's grounds and have themselves become beloved locals. The sign for Jim's restaurant is a classic of mid-century design that improbably promises both tacos and pastrami.

Mexican-Americans started coming to Boyle Heights after World War II, as American cities headed into a decline hastened by the rise of the suburb. Freeways cut up the neighborhood, which in 1961 became home to the inhuman concrete tangle known as the East L.A. Interchange. Boyle Heights also proved a crucible of gang violence, which was practically invented in Los Angeles; in 1992, there were 97 homicides attributed to the Hollenbeck Division, the local station of the Los Angeles Police Department. "Gang members were part of the scenery, like the shrubs finely coated by the freeway emissions from the nearby East L.A. interchange," Hector Becerra wrote in a recent recollection of growing up in Boyle Heights during the 1980s for the Los Angeles Times.

Somehow, Boyle Heights held together. Last year, Hollenbeck Station recorded only 14 murders. A line of the Metro light rail system now connects it to both downtown and the San Gabriel Valley. In 2005, Los Angeles elected a Boyle Heights native as its first Latino mayor, Antonio Villaraigosa. Today, there are new restaurants, coffee shops and galleries, many of them run by locals who want to keep the neighborhood's Chicano heritage alive. That imperative has been called gentefication (gentrification tempered by la gente, Spanish for "the people"), which suggests an organic improvement of a neighborhood by its Spanish-speaking entrepreneurs. For example, at the Primera Taza coffee shop, a café Americano is known as a café Chicano.

It was inevitable that art galleries would ford the Los Angeles River into Boyle Heights. The Arts District, a formerly decrepit section of downtown, has been growing more expensive; Annenberg Media found that rents rose 140 percent in parts of the neighborhood in the first 14 years of the new millennium. Between 2000 and 2012, rents in all of Los Angeles County also rose, but at the much slower rate of 25 percent.

In the three years since that study, new developments like the gigantic One Santa Fe residential-commercial complex have only made the neighborhood more attractive—and more expensive. Michael Maltzan, who designed the sinuous white slabs of One Santa Fe, is also working on the Sixth Street Viaduct, a $480 million span across the Los Angeles River that will also include much-needed parkland. That bridge will connect downtown directly to Boyle Heights. And though it isn't slated to open until 2020, plenty of Arts District refugees have already crossed the river.

On the refrigerator case at the Primera Taza, for example, is an anti-gentrification sticker. In that case sit bottles of artisanal kombucha.

'Burn Your Shit Down'

It is a sad irony that Boyle Heights, long a refuge for the unwanted, has become an insular neighborhood suspicious of outsiders. In 2014, a Latino gang called the Big Hazard firebombed African-American families in a housing project on the northern edge of the neighborhood. No one was injured, but the point was made. "Some black families immediately put in for emergency transfers to other housing projects," reported The Los Angeles Times.

About two weeks after the firebombing, a West Side brokerage called Adaptive Realty put up posters in the Arts District advertising a bike tour of Boyle Heights. "Why rent downtown when you could own in Boyle Heights?" the posters wondered, showing a fashionable woman astride an equally fashionable bike and promising "artisanal treats and refreshments."

The gentri-flyer, as it came to be known, drew a furious reaction. Someone called the agent who'd organized the event and threatened to "burn your shit down like the Watts Riots in '92." No artisanal treats were consumed.

In 2015, musical director Yuval Sharon premiered Hopscotch, a logistically complex opera that whisked audience members through Los Angeles in limousines. One of the stopping points was Hollenbeck Park, a large green space in the middle of Boyle Heights where weddings and quinceañeras are frequently held.

Residents took offense. A group called Serve the People Los Angeles brought protesters and the local high school's marching band to a Hopscotch performance, which they drowned out.

"Hopscotch Los Angeles and their art, their performers, their supporters, their capital, are not welcomed in Boyle Heights," Serve the People Los Angeles wrote after that day's confrontation in a blog post studded with quotations from Mao Zedong. That was the last time Hopscotch came to Boyle Heights.

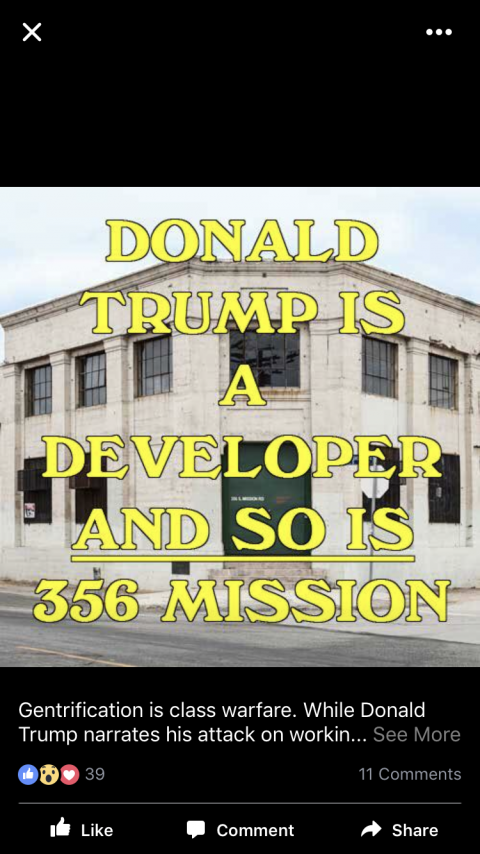

The first white-owned gallery to arrive in Boyle Heights was 356 Mission, settling in 2012 on a block director Ethan Swan told me was a dumping ground for mattresses and other unwieldy junk. The gallery's owner, Laura Owens, rented space in a warehouse that was otherwise unused.

At first, there were no problems, largely because the Anderson Street galleries had not yet attracted much public notice. That started to change with the arrival of Maccarone Gallery three years later. "It still has a dangerous quality—I kind of like that," the gallery's proprietor told The New York Times in the fall of 2015. "I like that we spent a fortune on security."

In response to that article, locals organized their first anti-gallery protest. A homemade flag offered a simple equation that may be impossible to resolve: "Gentrification = Racism."

If there was a declaration of all-out war, it took place on July 12, 2016, during a community meeting at the Pico Gardens housing project, the closest major residential cluster to Anderson Street. That was when the Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement made its demands most clearly. As one activist told the LA Weekly, "We have one pretty simple demand, which is for all art galleries in Boyle Heights to leave immediately and for the community to decide what takes their place."

'It Was Very Scary'

Maccarone is not the only gallery that treated Boyle Heights like a dystopian landscape with no culture of its own, no pride of place. For example, in September 2016, United Talent Agency—the influential agency based in Beverly Hills—opened UTA Artist Space. It inaugurated the venue with works by Kids director Larry Clark, paintings and photographs that seemed to glamorize drug use. That night, 20 or so protesters showed up in front of the space carrying a banner that declared, "Keep Beverly Hills out of Boyle Heights."

Eva Chimento is not from Beverly Hills. She is from Brooklyn, where her family operated a trucking company, navigating the complex intersection of organized labor and organized crime. Two and a half years ago, Chimento, who has lived in Los Angeles her entire adult life, divorced the lawyer to whom she had been married for 19 years. She was suddenly the single mother of a teenage daughter, and she had never worked anywhere but art galleries since she was herself a teenager. She decided she wanted to open her own art space, but the properties she saw in the Arts District were far too expensive—more expensive, she says, than even Beverly Hills.

One day, Chimento was driving across the Los Angeles River when she saw an elderly Latino ice cream vendor, a paletero, pushing his cart across the bridge. It was, she remembers, about 110 degrees outside, but she got out and helped him push his cart across the river, to its eastern embankment.

That was when she first saw Anderson Street. "It was dirty. It was gross. There were hookers and drug dealers on the street," she recalled when I visited her at Chimento Contemporary, a small exhibition space at the back a warehouse. She had displaced no one by coming to Boyle Heights, and she was making genuine efforts at inclusivity. One of the artists on display earlier this year was Monique Prieto, a Chicana whose "Hat Dance" series, shown by Chimento, used abstract shapes to allude to a classical Mexican ritual.

"It was very scary. It was completely desolate," Chimento continued. Other than the galleries that have taken hold here, South Anderson Street remains fairly desolate. There are warehouses nearby, and 18-wheelers wheeze through the neighborhood, raising dust and intimidating the rare pedestrian. The one non-art, non-industrial business I encountered on South Anderson Street was a brewery, relatively new to the neighborhood and very glad to have not incited the activists' righteous ire.

As a teenager, Chimento had gone into the Pico Gardens housing project to give art lessons, so she was familiar with Boyle Heights, who lived there and how, which is to say in a constant struggle against the conditions of an East Los Angeles existence. Anderson Street did not seem to her like Boyle Heights, but, rather, a no-man's land with plenty of unused commercial space. She opened her gallery there in 2015, when her funds consisted of $1,500. She says local high schoolers used to visit the gallery. Now, some of them want her to leave.

She is outraged by the accusation that she is a gentrifier. "They're targeting the wrong people," she says. "They're targeting business owners. They really need to be targeting the owners of the buildings." She wonders why the galleries are deemed enemies, while the Starbucks on East Olympic Boulevard is, presumably, a friend of the people.

In November, five days before the presidential election, several of the galleries were spray-painted with graffiti that said "fuck white art." The LAPD designated this a hate crime, though the gallerists insist they pleaded with the cops to avoid such an inflammatory charge.

They were right to suspect that a hate-crime accusation would only further enrage the activists. Back in August, LAPD officers had shot and killed a Boyle Heights teenager, Jesse Romero, who had been spray-painting graffiti on Cesar Chavez Avenue. Although officers claimed that Romero had pointed a gun at them and that his graffiti was gang-related, few in Boyle Heights were convinced. The response to the "fuck white art" graffiti signalled to some in the neighborhood that the LAPD cared more about the property of white gallery owners than the lives of brown children.

Increasingly, Chimento feels unsafe, and her daughter no longer comes around. Much like the activists who want her out of Boyle Heights, Chimento feels that economic forces have assailed her, pushed her into a corner. And much like them, she is determined to stay.

'The Opening Wedge of Totalitarianism'

To understand the suspicion fueling the anti-gallery movement, you have to leave Boyle Heights and walk—or, more likely, drive—north, toward a row of palm trees standing like emaciated sentries on a ridge of Elysian Park. Nestled in these hills is Dodger Stadium, one of America's last great ballparks.

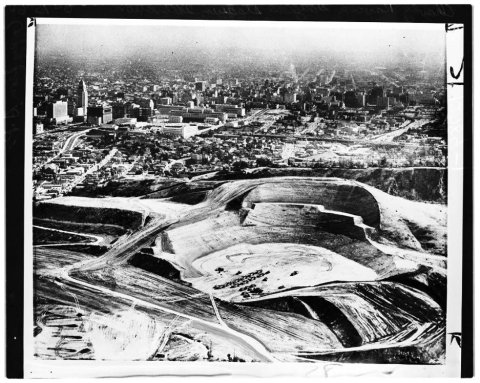

Angelenos frequently resort to a metonymic description of Dodger Stadium by calling it Chavez Ravine. That linguistic shorthand refers to the thriving Chicano neighborhood that once lined the hills. Some of the hills were flattened to make way for the stadium; those that remain are so thoroughly bisected by freeways that they have the feel of uninhabited atolls in the South Pacific. A pedestrian here is bound to have the bewildering experience, common in Los Angeles, of feeling that a sidewalk has suddenly turned into an on-ramp.

Little of the human settlement remains. As the historian Jerald Podair writes in his excellent new book, City of Dreams: Dodger Stadium and the Birth of Modern Los Angeles, "Chavez Ravine was home to a tightly knit, working-class Mexican American population" of several hundred families "living in relative isolation from the rest of Los Angeles." There was a rural feel, and some residents "kept chickens and other farm animals."

In 1949, the City Council decided to build public housing in Chavez Ravine, but a group called the Citizens Against Socialist Housing beat that back by depicting it, in Podair's words, as "the opening wedge of totalitarianism." Eight years later, civic leaders enticed Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley—who'd been frustrated in his plans to build a new stadium in Brooklyn to replace Ebbets Field—to bring his ball club to Southern California.

The residents of Chavez Ravine felt they were being forced to sell their land at preposterously low prices. "It's just as if somebody wants to buy the shoes that you are wearing and you don't want to sell them," one resident wrote to a local newspaper. "What right have they to give our land away?"

It was never in question who was going to win what came to be known as the Battle of Chavez Ravine, but the Chicano residents didn't leave meekly. One of the most ferocious holdouts was the Arechiga family, who had come to Chavez Ravine in 1923. The photograph of an Arechiga family member dragged down a flight of stairs by police officers is one of the lasting images of that fight.

The passion of the Defend Boyle Heights activists appears principled to some, embarrassingly naïve to others. Rose Garcia, a real estate agent in Highland Park, believes gentrification is good for Los Angeles's East Side. Certainly, it has been good for her, and for the Latinos whose houses she has sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Garcia's family, which is Puerto Rican, came to Highland Park in 1972, when it was still white. As more brown people came, white people fled. Then it got dangerous, with gangs taking over. "I don't see any reason it should lessen up," an LADP official confessed to the Los Angeles Times about the violence on the second day of 1992. "The gangs are just too active. If anything, there may be an increase."

But it did lessen up, if not right away. Whites priced out of the West Side of Los Angeles came to the city's Northeast, first to Silver Lake and Echo Park, then to Highland Park. Garcia started selling real estate 17 years ago; in 2013, she opened her own agency to handle what she calls the "big East Coast migration" to Highland Park.

Some accuse her of abetting gentrification. Garcia is OK with that. "Who is selling this property to you?" she wondered with derision. "It is a Hispanic person who moved here in the 1970s. That's the person that's capitalizing on this big push." If anyone is "getting fucked," she argued, it is the whites thrilled to pay $800,000 for a beat-up, two-bedroom bungalow.

Boyle Heights, though, is a renters' enclave. Its home ownership rate is only 11%, according to the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, meaning that most of its residents live at the whim of landlords. Garcia knows this, of course, but points to the city's relocation assistance rule, which can provide as much as $19,500 to a resident facing displacement. She finds the expectation of activists unrealistic. "Do you think it's fair in 2017 for you to pay $600 a month for a one bedroom? Let's be real here. I want a Ferrari, and I want to pay $300 a month."

What's the Endgame Here?

Efforts to broker a peace between the activists and the galleries have been rare and unsuccessful. The most earnest try was by Self Help Graphics & Art, a not-for-profit arts collective founded by a Franciscan nun in 1970. As an art gallery native to Boyle Heights, Self Help seemed to be the only group capable of calming tensions.

Last August, Self Help hosted a community meeting in its headquarters, a converted fish warehouse that fronts the Gold Line tracks. "In no time, the meeting went south," the Los Angeles Times reported, "as about a dozen mostly young activists, some wearing the brown berets of their 1960s Chicano Movement forebears, barged in. One woman covered her face with a red bandana. They accused Self Help Graphics of helping to roll the Trojan horse of gentrification into Boyle Heights by supporting art galleries popping up in the neighborhood."

When I visited Self Help, it was richly adorned with prints by Chicano and Latino artists, including works that explicitly addressed immigration, drug violence and indigenous culture. It was like the galleries of South Anderson only in the most literal sense, in that it displayed art, some of which was for sale. That art, though, could be bought for as little as $50. Some of it was made by high-schoolers, in studios that functioned, long ago, as seafood freezers.

Betty Avila, the associate director of Self Help, is a controlled and self-spoken woman plainly dismayed that her organization has been depicted as an enemy of the people. Luna, the Defend Boyle Heights activist, described ties to the real estate industry; Avila said such ties were fiction.

A native of Cypress Park, in the northeast of Los Angeles, Avila says she understands that Boyle Heights has always been an "oppressed" community. But she doesn't understand why Self Help is being targeted, especially since it has been in Los Angeles longer than some of the Boyle Heights activists have been alive.

"It's been confusing," she said. "I don't know what the endgame is there."

Maybe there is no endgame, the two sides exchanging blows until one of them falls exhausted to the mat. Late last month, activists walked into the BBQLA gallery, which is right down the block from Chimento Contemporary, and threw laundry detergent on people gathered there for an opening. Art was reportedly ruined as well.

This month, there was a protest in front of MaRS, or the Museum as Retail Space, another of the Anderson Street galleries. Luna, the Defend Boyle Heights activist, stood at the entrance to the gallery, speaking into a microphone, repeating that there was a boycott against the galleries.

A woman holding a baby came out to argue with one of the activists. As they shouted at each other, the child looked on, serene yet mildly confused.

Young Princelings and Old Ways

The story of Boyle Heights is not just a Los Angeles story. It is the story of the South Bronx, where artists have taken a foothold in the lofts of Alexander Avenue, in the shadow of public-housing towers. And it is the story of the Mission District in San Francisco, where young princelings of the tech economy have been steadily displacing the city's Latino immigrants. There are similar struggles in Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Miami, over what these cities once were, what they have become, what they will be.

The galleries moving to South Anderson Street are part of a globalized and sophisticated city of the 21st century, in which a tourist from Hong Kong or Paris might think nothing of trekking to Chimento Contemporary and paying $20,000 for one of its artistic offerings. Only the light coating of concrete dust on that tourist's shoes will suggest that this was once something else, that ferocious battles were fought over this land, with history, justice and community deployed as weapons.

But not everyone believes that battle is lost. There are some who believe that a global city is a city without soul, because a luxury condominium in Lisbon is a luxury condominium in Seattle, which is a luxury condominium in Lagos. For a city to have character and soul, it must have all the complex constituents of such a project, and that includes locals who work hard in unglamorous jobs, who at the end of the day pop open a can of domestic beer and drink it on the stoop, arguing about béisbol and listening to the yapping of little dogs.

That is what the activists in Boyle Heights believe, in any case. They understand that they are trying to hold back time itself. They don't care. This is their Los Angeles. This is their Boyle Heights.

Update: Defend Boyle Heights has denied involvement on the attack on the BBQLA gallery late last month. This article has been updated to reflect that assertion.